Beryl Markham lent me her wings while I was laid up on a hospital bed, almost paralyzed, with surgeons recommending that, in order for me to walk again, they would have to carve me up. Once they would leave, taking their medical insights with them, the weight of their Cartesian scientific history and experience under their arms, I, undecided about the advantages of scalpels, would look at Beryl, black and white against the green cover, and think of the demands of book reviewing, of separating an author’s words from mine, and sighing at the effort to which I am not equal. For authors’ words have, in many cases, not only inspired my own – they have become my own. Why must I differentiate between them when, to me, they form the whole of who I am, and who I want to be, and who, perhaps, I once was? How awkward the insertion of apostrophes, inverted commas, quotation marks, quotes, and citations – they all seem like so many little interruptions that accumulate and exhaust, both, the reader and I. I have exhausted myself in searching for a style. Enough! I must write. Caveat lector.

She can write rings around all of us, Hemingway once wrote. High praise indeed from a Nobel Laureate. Then again, Hemingway always seemed to me to be... well, somewhat too earnest, writing like a genius kid in junior high who never quite managed to graduate to university. If Beryl wrote rings around him, it was because she indeed wrote better. It was the same unelaborate, though not simplistic, style of Hemingway. But, unlike Hemingway, it was not journalism. Having said that, I like Hemingway. I do not like the image the media has built of him, and I do not like most of his work. But I like him all the same, for his Hills Like White Elephants – which took me years to understand, and, even then, only by aid of a critic’s appreciation – and for his Death in the Afternoon, where he taught me that the great thing is to last and get your work done and see and hear and learn and understand, and write when there is something that you know, and not before, and not too damned much after… But I digress, and Hemingway, too, will have his turn.

I am there, with her, when she sits down and eyes around the room for a beginning. I am her hand which turns the pages of a flying log which just happens to be there on the desk, that particular log and not any one of those numerous other logs that lie scattered about the shelves like old airplanes parked in protective hangars, their wings full of past adventures, wishing they could now write since they fly no more. My eyes are hers as they fall upon an inconspicuous entry, almost too ordinary, brief and indifferent:

DATE – 16 June 1935

TYPE AIRCRAFT – Avro Avian

MARKINGS – VP-KAN

JOURNEY – Nairobi to Nungwe

TIME – 3 hrs. 40 mins.

PILOT – Self

REMARKS – -

It concerns a routine flight, the transport of a canister of oxygen to a dying gold miner, dying of a lung disease; oxygen not as lifesaver but as final comfort, a final offering from the elements, from the very same elements which burnt his lungs as he sought his fortune. Her eyes, and mine, look upon this entry in this logbook, but she will not begin by telling this story. The facts can wait, as they always can. Instead, she dreams a little, and I begin to feel what Nungwe does to her and so to me. Where Sartre believed that anything which one names loses its innocence, Beryl proves him too completely wrong. For what are dreams but innocence, and dreams of places are but innocence located in names, names like Tsavo, Muthaiga, Mwanza, Nakuru, the Rongai Valley, the Mau Escarpment, Kabete Station, Voi - ah! Voi, which presumed itself a town back then, but was hardly more than a word under a tin roof! - and Mombasa. Mombasa! If only more places were named like that! The name itself ensures the place will never lose its dreamy innocence of times long gone, and of times that could have been, and of times yet to come. How alive Mombasa feels, even merely as a name, from a place like New York, or Vienna, or London. It is the gateway to that world of which you have always remained unsure: did it once exist, or is it somewhere still? That world which lives and grows without adding machines and newsprint and brick-walled streets and the tyranny of clocks. That world where one is unable to discuss with any intelligence or reason the boredom of being alive. For such intellectual endeavors, London is the best place to be. Boredom, like hookworm, is endemic indeed.

I do not remember how, or when, I first looked upon a map and saw the world, how I first fused the idea of a flat cartographic drawing with the roundness of the globe, how I first pointed to a dot with a name and proclaimed ‘I am here’ with the confidence that requires no courage. But ever since then, my confidence in maps has never left me, and nor has the assuredness they give me to proclaim my location. My upbringing always seemed to me as if I had been born into so many locations at once. My life began with maps, as I was hauled across continents, into new landscapes, peopled by all shades and humors, and into new languages that became my own. Maps were my first education, my first texts, my first entertainment, and my first love of symbols on paper. Maps were where life was reflected and, in being so, where life itself opened up to me. In adult years, I discovered the pleasures, and the challenges, of the cartographic science and the mapping art, and was thus happy to find the child in the man I am. One must never lose sight of childhood dreams. They still have the power to move us from place to place, and so progress, and lend some wisdom to our oh-so-adult ways.

It was when I developed my mature, scholarly taste for maps that Beryl appeared, with Hemingway’s echo that I should read her, not him. She flew me 245 pages over East Africa in her biplane, in darkness and in sunlight, from the stench of blackwater in Nungwe, to the bright green of her father’s farm at Njoro, over the Kikuyu Reserve and into the Yatta in search of stranded Blix. Indeed, it was upon finding Blix and Winston that she told me something that has remained with me always, not for its allusions to practicality, but for its sheer poetic resonance. I had never realized before, she said, how quickly men deteriorate without razors and clean shirts. They are like potted plants that go to weed unless they are pruned and tended daily. A single day’s growth of beard makes a man look careless; two days’, derelict; and four days’, polluted. Blix and Winston had not shaved for three. Since then, on days when I decide not to shave, I cannot help but think of Beryl, and I picture Blix looking like an unkempt bear disturbed in hibernation.

My dwelling on this incident is, in part, because it was the beginning of the end of Beryl’s Africa, and mine, but mostly because of how she marked that end as a beginning. It came with no obvious reason, that goodbye. She simply looked up one evening and asked, ‘Want to fly to London, Blix?’ He said yes, without as much as a consideration, always the adventurer, always the child. By then Karen had gone, and Blix and Beryl were all that remained. It seemed as natural as birds migrate that they too should finally return to their northern lands, or die along with the times that Africa was now devouring in its desire to change. And yet ‘return’ would be the wrong term to use. Exile would be more accurate. For even if Africa was indifferent to them, even if they had learnt - like all those of us who have lived Africa and made it our home knowing that it can never be ours - that it would never succumb to some imposed domestication, return to Europe was exile in Europe away from Africa, and there is no truer way of describing it than that. This exile, for having haunted them all their lives, was a decision well-prepared, and thus needing no more than Blix’s unreflective yes.

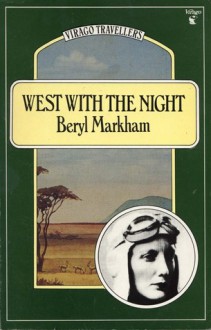

It was this decision that brought maps and goodbyes and new beginnings all together suddenly one day, at a pilot’s hour bundled in mist. By this time, Beryl was flying a Leopard Moth, a high-wing cabin monoplane. I gazed at it with so much nostalgia for the biplanes of old that... Plus ça change… en effet plus ça change. I do not know what she saw in my face. Maybe she saw a child on his first day of school, facing the world as it suddenly opens with all its terror and its overwhelming possibilities, and, knowing how children can love maps, maybe she wanted to reassure me that I could follow her, and so be with her, even if only cartographically. And so she gave me a green covered book, with a photograph of her, complete with flyer cap and goggles restless above her eyes. And as my fingers wrapped around it, she held it too and said:

“A map in the hands of a pilot is a testimony of a man’s faith in other men; it is a symbol of confidence and trust. A map says to you, ‘Read me carefully, follow me closely, doubt me not.’ It says, ‘I am the earth in the palm of your hand. Without me, you are alone and lost.’ Here is a valley, there a swamp, and there a desert; and here is a river that some curious and courageous soul, like a pencil in the hand of God, first traced with bleeding feet. Here is your map. Unfold it, follow it, then throw it away, if you will. It is only paper. It is only paper and ink, but if you think a little, if you pause a moment, you will see that these two things have seldom joined to make a document so modest and yet so full with histories of hope or sagas of conquest.”

She then let go of the book and turned toward the plane and an impatient Blix. But she stood a moment, taking in the humidity of the morning air. Perhaps she wanted to give the mist of cloud a little more time to rise. And so she looked at me again and said:

“You can live a lifetime and, at the end of it, know more about other people than you know about yourself. You learn to watch other people, but you never watch yourself because you strive against loneliness. If you read a book, or shuffle a deck of cards, or care for a dog, you are avoiding yourself. The abhorrence of loneliness is as natural as wanting to live at all. If it were otherwise, men would never have bothered to make an alphabet, nor to have fashioned words out of what were only animal sounds, nor to have crossed continents, each man to see what the other looked like.”

And she flew away.

Some time later I received a postcard from Libya. By then she was in England and already planning the Atlantic flight which would bring her fame. The postcard was of the corniche in Tripoli, draped in palm trees. On the back, in a quick hand, was written the following:

“Last night, Blix and I were taken in by a local woman. She showed us to two rooms, not even separated by a door. Everything lay under scales of filth. ‘All the diseases of the world live here,’ I said to Blix. He was laconic. ‘So do we, until tomorrow,’ he said. And so we did. And now we’re off to cross the Med.”

Beryl and Blix left Africa exactly how she taught me to leave places that one has lived in and loved and where all one’s yesterdays are buried deep: quickly. They did not turn back, and never believed that an hour one remembers is a better hour because it is dead. Passed years seem safe ones, vanquished ones, while the future lives in a cloud, formidable from a distance. Pilots know that the cloud clears as you enter it.

Log in with Facebook

Log in with Facebook