Currently FREE at amazon!

Currently FREE at amazon!

Book 2/2014.

Cross-posted from my wordpress blog:

Agnes Grey was published in 1847. This was an exceptionally good year for the Brontes – 1847 saw the publication of Agnes Grey, Wuthering Heights and Jane Eyre, which combined to form a trifecta of Bronte awesomeness, and includes the two most well-known books by the Brontes.

Anne Bronte was the youngest Bronte, and remains the least well-known of the three sisters. She died extraordinarily young, at 29 years of age. Her only other published work isThe Tenant of Wildfell Hall, which was out of publication for many years at the behest (as I understand it) of the eldest and most prolific sister, Charlotte. Agnes Grey was published under the pseudonym Acton Bell.

Agnes Grey is a bildungsroman, or a coming of age story, in this case, of the titular character, Agnes. The book begins with Agnes and her sister living at home with her parson father and their mother. Father unwisely invests money with a merchant who ends up dying, and the family loses all their savings. Agnes, in a bid for independence, decides to go to work as a governess. She ultimately obtains a position as a governess for a wealthy family, and leaves the family homes and goes out in the world.

I really liked this book. I was not a fan of Wuthering Heights when I read it, although I did love Jane Eyre. Agnes Grey is, in my mind, less sophisticated thanJane Eyre, but has many of the same themes. Anne Bronte used the book as a vehicle to explore oppression of women, animal cruelty, love, marriage and religion.

I have been listening to one of the Great Courses on the Victorian era as well as reading books that were written in and during the Victorian era. There are two lectures, so far, that dealt directly with women – one about upper class women and one about working class women. The circumstances for working glass girls/women were fairly dire, actually, and Agnes Grey does a good job of illustrating that direness. Agnes finds herself working for a family that is clearly inferior to her in most domains – she has more common sense, more integrity, she is better educated, she has a greater work ethic, she is more useful. The only area that they exceed her is in that of wealth. They are rich, she is poor.

Each of the families, nonetheless, considers themselves and is considered by society, to be her superior. The Bloomfield family – the first family where she is a governess – has raised their eldest son to be an overtly cruel human being. He is abusive – both verbally and at times physically – to Agnes, and he casually tortures small animals. His education is a total loss because no one exerts even the slightest degree of control over him to force him to learn, and being the eldest son of a wealthy family, there is no incentive for him to be anything other than what he desires to be. Agnes is dismissed when she fails to educate him.

The second family, the Murray family, is less casually abusive but concomitantly more frivolous. Agnes is governess to their two youngest daughters. The eldest, Rosalie, is a pretty ornament who thinks only of flirtations and marriage. Matilda, the youngest, is a foul-mouthed tomboy who is also a liar (I confess a bit of partiality to poor Matilda. She’s so screwed in that era). The appearance is the reality for this family, and nothing matters but what is on the surface.

Agnes Grey is based on Anne Bronte’s experience as a governess. One of the things that I found interesting was how little actual learning was going on in the schoolroom. I am sure that not every Victorian wealthy family was the same, but Agnes was given no authority at all, and was therefore ignored at best and abused at worst. I cannot think of few worse jobs than being charged with the education of spoiled, entitled, in some cases quite possibly sociopathic, children who have total power over your life. It’s a nightmarish prospect.

It is easy to wax nostalgic for the past, and for eras like the Victorian era. Reading a book like Agnes Grey is a useful exercise to remind us that we should not idealize the past.

I will have more to say about Agnes Grey, and the other Bronte sisters, and probably the Victorians in general, over the course of the rest of the year. I would probably call Agnes Grey a minor masterpiece, but a masterpiece nonetheless. I have heard that Anne’s second book, The Tenant of Wildfell Hall is even better.

Ebook, read on Open Library.

Think of this as a literature seminar with a really interesting professor who at times will read you passages of books and then tie them all back to the central theme. In addition, you'll get information about the society the books were written in, as well as lots of biographies of various writers. If you haven't read some of the literature (Wuthering Heights, Lady Audley's Secret, etc.) then there will be some spoilers. This however is a good thing, because the focus here is using those stories as examples, and if the author was coy with the plot (and thus not spoiled anything) we'd not be able to understand the reference. Also this is extremely helpful because some of the more obscure books referenced are not going to be easy to find, even with Gutenberg, and so you don't mind having the plot explained.

I don't know that I agree with everything Showalter has said about some of the books and authors - but I can say that almost every other page I was either writing down a quote or piece of history that interested me, or I was jotting down another name to the list of women authors I needed to look up and learn more about. The book will practically write you a To Read list, some of which I'm sure are core women's studies lit I never got around to reading.

Contents

I. The Female Tradition

II. The Feminine Novelists and The Will To Write

III. The Double Critical Standard and the Feminine Novel

IV. Feminine Heroines: Charlote Bronte and George Eliot

V. Feminine Heroes: The Woman's Man

VI. Subverting the Feminine Novel: Sensationalism and Feminine Protest

VII. The Feminist Novelists

VIII. Women Writers and the Suffrage Movement

IX. The Female Aesthetic

X. Virginia Woolf and the Flight into Androgyny

XI. Beyond the Female Aesthetic: Contemporary Women Novelists

Biographical Appendix and Selected Bibliography

Showalter provides many examples from books and contemporary publications to support her statements, but quoting all of that in full would be even more lengthy. At the same time, I also want to save many quotes that I personally was interested in. (I really loved the Woman in White/Lady Audley comparison discussion in Ch 6.)

Quotes:

Acknowledgments, p vii:

"In the atlas of the English novel, women's territory is usually depicted as desert bounded by mountains on four sides: the Austen peaks, the Bronte cliffs, the Eliot range, and the Woolf hills. This book is an attempt to fill in the terrain between these literary landmarks and to construct a more reliable map from which to explore the achievements of English women novelists."

Chapter 1, The Female Tradition

p 11: "...This book is an effort to describe the female literary tradition in the English novel from the generation of the Brontes to the present day, and to show how the development of this tradition is similar to the development of any literary subculture."

"....what Germaine Greer calls the "phenomenon of the transcience of female literary fame"; "almost uninterruptedly since the Interregnum, a small group of women have enjoyed dazzling literary prestige during their own lifetimes, only to vanish without trace from the records of posterity."

p. 18: - "The works of Mary Wollstonecraft were not widely read by the Victorians due to the scandals surrounding her life."

p. 20: "...even the most devout women novelists, such as Charlotte Yonge and Dinah Craik, were aware that the "feminine" novel also stood for feebleness, ignorance, prudery, refinement, propriety, and sentimentality, while the feminine novelist was portrayed as vain, publicity-seeking, and self-assertive."

p. 21: "...The novelists publicly proclaimed, and sincerely believed, their antifeminism. By working in the home, by preaching submission and self-sacrifice, and by denouncing female self-assertiveness, they worked to atone for their own will to write.

...Victorian women were not accustomed to choosing a vocation; womanhood was a vocation in itself."

p. 25: "Coarseness" was the term Victoians readers used to rebuke unconventional language in women's literature. It could refer to the "damns" in Jane Eyre, the dialect in Wuthering Heights, the slang of Rhoda Broughton's heroines, the colloquialisms in Aurora Leigh, or more generally to the moral tone of a work, such as the "vein of perilous voluptuousness" one alert critic detected in Adam Bede.

Chapter 2, The Feminine Novelists and The Will To Write

p. 37: "...This uniformity of social origin is true of English writers generally, but is more extreme in the case of women, who were even less likely than men to be the children of the laboring poor. Women novelists were overwhelmingly the daughters of the upper middle class, the aristocracy, and the professions. ...Tess Dubeyfield did not write fiction.Yet the comments of critics in Victorian journals give the impression that every woman in England was shouldering her pen."

p. 37-8: "...anyone who turns to the publishers' advertisements at the back of a Victorian novel will soon be aware that scores of books have disappeared along with their authors. For example my copy of Mrs. Craik's A Noble Life (published by Hurst & Blackett, 1866) who are Mrs. G. Gretton, author of The Englishwoman in Italy; Beatrice Whitby, author of five novels; who are Mabel Hart, E. Frances Poynter, and Martha Walker Freer? They have all slipped through the literary historian's net, as have half of the women writers listed month by month in the Englishwoman's Review in the 1870s."

p. 40: "...it is important to remember that "female dominance" was always in the eye of the male beholder. The Victorian illusion of enormous numbers [of female writers] came from overreaction of male competitors, the exaggerated visibility of the woman writer, the overwhelming success of a few novels in the 1840s, the conjunction of feminist themes in fiction with with feminist activism in England, and the availability of biographical information about the novelists, which made them living heroines, rather than sets of cold and inky initials."

p. 42: "The classical education was the intellectual dividing line between men and women; intelligent women aspired to study Greek and Latin with a touching faith that such knowledge would open the world of male power and wisdom to them. ...It is a commonplace for an ambitious heroine in a feminine novel to make mastery of the classics the initial goal in her search for truth."

p. 44: "...It was not until much later that women writers began to understand that the classical curriculum and the conventional schoolroom offered a very limited education, and to appreciate that their own efforts may even have given them an advantage over their brothers."

p. 47: "...Furthermore, women writers were likely to be dependent on their earnings and contributing to the support of their families, and not, as has been conjectured, indulging themselves at the expense of fathers and husbands."

p. 61: "...One of the distinguishing characteristics of the female novelists is the seriousness with which they took their domestic roles. ...But neither condescension nor indignation is warranted. Up until about 1880 feminine novelists felt a sincere wish to integrate and harmonize the responsibilities of their personal and professional lives. Moreover, they believed that such a reconciliation of opposites would enrich their art and deepen their understanding."

p. 70: "...It was not exactly that critics revered motherhood and its wisdom, but that they regarded mothers as normal women; the unmarried and the childless had already a certain sexual stigma to overcome. In the early part of the century, attacks on the barren spinster novelist were part of the common fund of humor."

Chapter 3, The Double Critical Standard and the Feminine Novel

p. 74 -75: "...As it became apparent that Jane Austen and Maria Edgeworth were not aberrations, but the forerunners of female participation in the development of the novel, jokes about dancing dogs no longer seemed an adequate response."

p. 83: "Rather than protesting against such criticism, women writers, as we have seen, reinforced it by playing down the effort behind their writing, and trying to make their work appear as the spontaneous overflow of their womanly emotions."

p. 86: "...Women novelists might have banded together and insisted on their vocation as something that made them superior to the ordinary women, perhaps even happier. Instead they adopted defensive positions and committed themselves to conventional roles. ...The feminine writers' self-abasement backfired and caused the kind of patronizing trivialization of their works found in George Smith's obituary of Mrs. Gaskell: "She was much prouder of ruling her household well... than of all she did in those writings."

p 91: "...When the authors behind the pseudonyms [Eliot and Bronte] were revealed to be women, critics were dismayed. The main difference between the two episodes was that Charlotte Bronte had been shocked, dismayed, and hurt to discover that her realism struck others as improper; George Eliot had seen what happened to Charlotte Bronte, and was prepared."

Critics looked to find someone to blame for "coarseness" in Jane Eyre, like Bramwell, the author's brother, p. 93: "The Quarterly Review looked closer to home, at the influence of Bramwell, "thoroughly depraved himself, and tainting the thoughts of all within his sphere." Many readers, including Charlotte Yonge, felt that Branwell's influence on his sisters had been dastardly, but they found it comfortably in accordance with their notions of male and female temperament."

Chapter 4, Feminine Heroines: Charlotte Bronte and George Eliot

p. 102: "By 1853 Austen's name had become a byword for female literary restraint, as is demonstrated by the protest of a critic for the Christian Remembrancer: "'A writer of the school of Miss Austen' is a much-abused phrase, applied now-a-days by critics who, it is charitable to suppose, have never read Mrs. Austen's works, to any female writer who composes dull stories without incident, full of level conversation, and concerned with characters of middle life."

p. 121 "...the image of the "maniacal and destructive woman" closely parallels that of the sexually powerful woman: "Menstruation, 19th century physicians worried, could drive some women temporarily insane; menstruating women might go berserk, destroying furniture, attacking family and strangers alike... Those 'unfortunate women' subject to such excessive menstrual influence," one doctor suggested, "should for their own good and that of society be incarcerated for the length of their menstrual years."

Chapter 5, Feminine Heroes: The Woman's Man

136: "It is customary for critics of the Victorian novel to see women's heroes as fantasy lovers, daydreams of romantic suitors. Critics have been rather slow to perceive that much of the wish-fulfillment in the feminine novel comes from women wishing they were men, with the greater freedom and range masculinity confers. Their heroes are not so much their ideal lovers as their projected egos."

140: cite in Carol Norton, Lost and Saved: ""Ever since Jane Eyre loved Mr. Rochester, a race of novel-heroes have spring up... Brutal and selfish in their ways, and rather repulsive in person, they are, nevertheless, represented as perfectly adorable, and carrying all before them, like George Sand's galley slave." These heroes do have a decided family resemblance. They are not conventionally handsome, and often are downright ugly; they have piercing eyes; they are brusque and cynical in speech, impetuous in action. Thrilling the heroine with their rebellion and power, they simultaneously appeal to her reforming energies."

140: "...The problem with the brute hero, the reason that he was considered so much a feminine property, was not that he was an unconvincing man, but that to the conservative male Victorian mind he was unlovable."

p 142-3 "Men, it appears, saw these heroes as tyrants who took advantage of helpless heroines, but nothing could have been further from their author's intentions. At least one woman critic recognized the appeal of the rough lover. Mrs. Oliphant, who personally tended to portray the safer, blander, clerical hero, shrewdly observed that the brute flattered the heroine's spirit by treating her as an equal rather than as a sensitive, fragile fool who must be sheltered and protected. ...Like the dark heroes in Scott's novels, the descendants of Rochester represent the passionate and angry qualities in their creators."

Chapter 6, Subverting the Feminine Novel: Sensationalism and Feminine Protest

p 158: "As Kathleen Tillotson points out, "the purest type of sensation novel is the novel-with-a-secret." For the Victorian woman, secrecy was simply a way of life. The sensationalists made crime and violence domestic, modern, and suburban; but their secrets were not simply solutions to mysteries and crimes; they were the secrets of women's dislike of their roles as daughters, wives, and mothers."

p 160: "In many sensation novels, the death of a husband comes as a welcome release, and women escape from their families through illness, madness, divorce, flight, and ultimately murder. ...Dr George Black warned in 1888 that incautious perusal of such novels had a "tendency to accelerate the occurrence of menstruation.""

162, on The Woman In White: "Collins also creates an active, intelligent female character in Laura's stepsister, Marian Halcombe, but he takes care to make her unfeminine and ugly - she is the only Victorian heroine of my acquaintance with a mustache. ... Marian Halcombe, as her first name suggests, is an anomalous figure somewhat similar to George Eliot (Collins did not like women novelists)."

165, Lady Audley's Secret: "The dangerous woman is not the rebel or the bluestocking, but the "pretty little girl" whose indoctrination in the female role has taught her secrecy and deceitfulness, almost as secondary sex characteristics. She is particularly dangerous because she looks so innocent."

p 165 Footnote 28: "Mrs Oliphant credited Braddon with setting a new fashion: "She is the inventor of the fair-haired demon of modern fiction. Wicked women used to be brunettes long ago, now they are the daintiest, softest, prettiest of blonde creatures; and this change has been wrought by Lady Audley and her influence on contemporary novels."

166: "Braddon's villain is Wilkie Collins' victim, and Braddon's satire of the conventions of The Woman in White extends to many other details. Throughout her novel, Braddon shows that a determined woman can liberate herself by actively applying the methods through which Collins' passive heroine is nearly destroyed."

169: Discussion of the Constance Kent case, notably in Juliana Ewing's Six to Sixteen (also in the Suspicions of Mr Whicher)

Chapter 7, The Feminist Novelists

184-5: "...This time around, women rejected the passivity and the non competitive separation of spheres basic to the feminine ideal. ...While their male contemporaries, such as Gissing, Moore, and Hardy, imagined a New Woman who fulfilled their own fantasies of sexual freedom (a heroine made notorious to feminists' disgust, by Grant Allen's 1895 best seller The Woman Who Did), feminist writers of the 1880s and 1890s demanded self-control for men rather than license for themselves. ...Their version of New Womanhood, though not as sensational as Allen's, was probably more pragmatic, and probably more threatening."

187: "To sheltered and sexually naive ladies, the revelations of the Contagious Diseases Acts campaigns (1864-1884) came with traumatic force. The campaign reached its full strength at just about the time that The Subjection of Women appeared. On December 31, 1869 the Daily News published a manifesto demanding the abolition of the Acts that was signed by 124 prominent women, including Florence Nightingale and Harriet Martineau. From then on, respectable women were confronted with an ever-escalating series of shocking stories of male brutality, profligacy, and vice. ...The policeman and the doctor became agents of the state in their forcible examinations of women accused of prostitution. ...The suicide of an innocent suspect, Mrs. Percy, in 1875, consolidated the view of a male alliance dedicated to the persecution of women."

Footnote 8, p 187: "The Contagious Diseases Acts, instituted during the Crimean War, attempted to control syphilis by enforced examination, detection, and treatment of prostitutes in garrison towns. Women objected because men were neither examined nor punished for their part in the transactions."

Footnote 9, p 188 "Between 1880 and 1900 about fifteen hundred infants died annually of hereditary venereal infections."

p. 191 "...[Ellis] Ethelmer's Woman Free (1893), a long poem in heroic couplets, celebrates the coming end of the menstrual cycle."

Chapter 8, Women Writers and the Suffrage Movement

p 216, Elizabeth Barret Browning: "considering men and women in the mass, there is an inequality of intellect."

p 217, Florence Nightingale: "there are evils which press more hardly on women than the want of the suffrage."

p. 217, Beatrice Potter: "Later...recanted; her explanation of her earlier motives probably speaks for other women as well: "At the root of my anti-feminism lay the fact that I had never myself suffered the disabilities assumed to arise from my sex."

p 222, About the book The Convert: "...[Elizabeth] Robins repeatedly suggests that the handling of the suffragettes had brutally sexual significance, a fact that should have been obvious but was repressed in contemporary historical accounts. In the later years of the suffrage campaign, forcible feeding by tubes through the nostrils or down the throat became the standard procedure for treating hunger-striking suffragettes in the prisons; like the Lock Hospital examinations of the Contagious Diseases Act, the whole struggle took on the quality of a rape."

p 224, Elizabeth Robins, Woman's Secret, WSPU pamphlet: "Contrary to the popular impression, to say in print what she thinks is the last thing the woman-novelist or journalist is so rash to attempt. Here even more than elsewhere (unless she is reckless) she must wear the aspect that shall have the best chance of pleasing her brothers. Her publishers are not women."

p 226 Anti-suffrage women: "Some women writers, like "John Oliver Hobbes" (Mrs. Craigie), emulated George Eliot's majestic reserve and continued to see themselves as exceptions to the general inferiority of women: "I have no confidence in the honor of the average woman or her brains.The really distinguished women have been trained and influenced by men, and a man-hater I distrusts and detest - she has the worst qualities of both sexes invariably."

p 232, footnote 38: "McAlmon writes of Harriet Weaver: "When she was nineteen she was caught reading George Eliot's Millon the Floss and was publicly repreimanded from the pulpit by the village minister." [In the book Being Geniuses Together, McAlmon and Boyle]

Chapter 9, The Female Aesthetic

p 243: "Just as the Victorians had maintained that women were to emotionally involved and anarchic to judge personality, let alone history, women now sweetly hinted that men were too caught up in the preservation of a system to comprehand its meaning."

p 244-245 "Other women - Stella Benson was one - insisted vehemently "on being a writer first and a wife second; a man would insist and I insist. A hundred years hence it will seem absurd that a woman should have to say this, just as it would seem absurd now if we shuold hear that Mr William Blake's wife wanted him to take up breeding pigs to help her and he obstinately preferred writing poetry." But it came to nothing in the end. When the crisis came, women went bitterly with their husbands, as they had always done."

p 249, about Dorothy Richardson: "...When Charles Richardson was finally declared bankrupt in 1893, his wife's invalidism was complicated by deep depression. Dorothy, feeling "trapped and helpless," had to respond to, and care for, her mother; in November 1895 they went on a desperate holiday together to Hastings. But Mrs Richardson was by then too despondent and alienated to be helped, and Dorothy returned one afternoon from a walk to find her mother dead in their room, having cut her throat with a carving knife."

p 257: "They had fought to have a share in male knowledge; getting it, they decided that there were better ways of knowing. And by "other" they meant "better"; the tone of the female aesthetic usually wavered between the defiant and the superior."

Chapter 10, Virginia Woolf and the Flight into Androgyny

p. 264: "Androgyny was the myth that helped her evade confrontation with her own painful femaleness and enabled her to choke and repress her anger and ambition. Woolf inherited a female tradition a century old; no woman writer has ever been more in touch with - even obsessed by - this tradition than she; yet by the end of her life she had gone back full circle, back to the melancholy, guilt-ridden, suicidal women - Lady Winchelsea and the Duchess of Newcastle - whom she had studied and pitied."

p. 264: "In her fiction, but supremely in A Room Of One's Own, Woolf is the architect of female space, a space that is both sanctuary and prison."

p. 274: Virginia Woolf's treatment for her "attack of madness": "Dr. Mitchell specialized in cures of neurotic women through a drastic treatment that reduced them "to a condition of infantile dependence on their physician." The ingredients of the rest cure were isolation, immobility, prohibition of all intellectual activity, and overfeeding, accompanied in some cases by daily massage. ...Besides forcing a women to stifle the drives and emotions that had made her sick with frustration in the first place and depriving her of intellectual outlets for their expression, the rest cure was a sinister parody of idealized Victorian femininity: inertia, privatization, narcissism, dependency."

p. 288-9 "She had taken to heart the cautionary tales to be found in the lives of earlier women writers. She had seen the punishment that society could inflict on women who made a nuisance of themselves by behaving in an uncivilized manner. It seems like a rationalization of her own fears that Woolf should have developed a literary theory that made anger and protest flaws in art."

Chapter 11, Beyond the Female Aesthetic: Contemporary Women Novelists

p. 299-300 "With each decade up to the 1960s feminism seemed more irrelevant to women who were persuaded that in leading "emancipated" individual lives, they had overcome the limitations of the feminine role."

p. 303 "The distress of Sylvia Plath's mother over the "ingratitude" of The Bell Jar suggests how difficult it has been for women to transcend social and familial pressures to write only what it pleasant, complimentary, and agreeable."

p. 318 "Even in [Elizabeth] Hardwick's terms, it is now possible for women to have some of the violent male experiences she valued so highly as literary material, to write, if they wish, about war and torture. ...More importantly, we are discovering how much in female experience has gone unexpressed; how few women, as Virginia Woolf said, have been able to tell the truth about the body, or the mind. ...But the denigration of female experience, the insistence that women deal with "the real business of the world," is also destructive. ...Their [the critics] theories of the transcendence of sexual identity, like Woolf's theory of androgyny, are at heart evasions of reality."

Even though this is already ridiculously long, I read this back when I was using Goodreads. So here's the Reading Progress section:

| 03/05/2013 | page 19 | 5.0% |

"I was worried this would happen with this book - currently only up to pg 19 and already have a list of authors to check out, some of which are new to me. Will see if all of them exist on Gutenberg, and how many I can't resist downloading."

|

|

| 03/05/2013 | page 19 | 5.0% |

"I'd not heard of Mary Brunton, for instance, who only had three books published, then died in childbirth. (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mary_Bru...)"

|

|

| 03/05/2013 | page 30 | 7.0% |

""In the 1890s the three-decker novel abruptly disappeared due to changes in its marketability" - somehow I don't think the same will happen with today's multi-novel series. (I'm weird, I don't like buying into those until the series is done. I call it my Han Solo Forever Stuck in Carbonite Fear.)"

|

|

| 03/06/2013 | page 30 | 7.0% |

"Randomly - and reading this book has only made me look this up and realize - Virginia Woolf has 6 volumes of collected essays. Even at this date there is not a full collected volume of all of them, either in paper or ebook. This seems wrong."

|

|

| 03/06/2013 | page 67 | 17.0% |

"Quote from Middlemarch: "She may read anything now she's married.""

|

|

| 03/07/2013 | page 75 | 19.0% |

"Note to self, add list of women authors that I've discovered or been reminded of, whose books are available online."

|

|

| 03/07/2013 | page 75 | 19.0% |

""As late as 1851, there were a few hardy souls who continued to deny that women could write novels." - saying it took the "properly masculine power of writing books" - ah, the 1800s, such fun."

|

|

| 03/07/2013 | page 77 | 20.0% |

""Victorian physicians and anthropologists supported these ancient prejudices by arguing that women's inferiority could be demonstrated in almost every analysis of the brain and its functions. They maintained that, like the "lower races," women had smaller and less efficient brains, less complex nervous development, and more susceptibility to certain diseases, than did men.""

|

|

| 03/07/2013 | page 79 | 20.0% |

""Since the Victorians had defined women as angelic beings who could not feel passion, anger, ambition, or honor, they did not believe that women could express more than half of life.""

|

|

| 03/07/2013 | page 85 | 22.0% |

"1862, Gerald Massey: "Women who are happy in all home-ties and who amply fill the sphere of their love and life, must, in the nature of things, very seldom become writers.""

|

|

| 03/10/2013 | page 95 | 25.0% |

"Particularly hard to read that Charlotte Bronte got such grief from critics because her writing in Jane Eyre was 'un-feminine.' Because her characters felt passion and she wrote her men too realistically (cursing, forceful words = unwomanly writing). Add to list of reasons you don't want to travel back in time to their generation."

|

|

| 03/11/2013 | page 95 | 25.0% |

"After liking the book Adam Bede when he thought the author was a man, William Hepworth Dixon went on to make catty remarks once George Eliot was out'd as female. He was also known for reviewing his OWN BOOKS favorably under a pseudonym. So yeah, sockpuppetry self-praise, it's historical. And still just as worthy of mocking."

|

|

| 03/11/2013 | page 96 | 25.0% |

""The Brontes, in their radical innocence, confronted all sexually biased criticism head on. Charlotte constantly had to be restrained by her publishers from attacking critics in the prefaces to her books, and she frequently wrote directly to reviewers and journals in protest." - and suddenly we all love Charlotte more, right?! Note that here any protest at all is radical for a woman."

|

|

| 03/11/2013 | page 106 | 28.0% |

"Harriet Beecher Stowe wrote George Eliot to describe a two hour conversation she (Stowe) had in a seance with Charlotte Bronte. Footnote info: via The George Eliot Letters V (and cite hooha), then author's note: "Eliot was skeptical." Now making note to read those letters."

|

|

| 03/11/2013 | page 135 | 35.0% |

""Like her sisters Anne and Emily, Charlotte [Bronte] might have shown men drunken and violent. But it did not pay, as she learned from Wuthering Heights and The Tenant of Wildfell Hall, for ladies to show how much they knew about men's lives.""

|

|

| 03/12/2013 | page 140 | 37.0% |

""The influence of Jane Eyre was international; within a year of its publication, an American critic wrote with mock terror about the "Jane Eyre fever" reaching epidemic proportions - young men caught it and began to swagger and swear in the Rochester style.""

|

|

| 03/12/2013 | page 156 | 41.0% |

""In the 1840s the success of women novelists had been perceived as a female invasion; in the 1860s women writers' advances were often perceived as a female monopoly.""

|

|

| 03/12/2013 | page 158 | 41.0% |

""Florence Marryat wrote her first novel, Love's Conflict (1865), "in the intervals of nursing" her eight children, all stricken with scarlet fever.""

|

|

| 03/12/2013 | page 159 | 42.0% |

""Like the domestic novelists of the previous generation, the sensationalists encouraged a special relationship, a kind of covert solidarity, between themselves and their readers. The audience for the sensation novel was, or was widely assumed to be, female, middle-class, and leisured.""

|

|

| 03/12/2013 | page 160 | 42.0% |

"Ok, you're not going to believe this one. 1888, a doctor warned that reading sensationalist novels could "accelerate the occurrence of menstruation." [facepalm]"

|

|

| 03/12/2013 | page 186 | 49.0% |

"I am really enjoying these footnotes: #6, citing examples of Darwinism applied to feminist writings; Frances Swiney, The Cosmic Procession (1906): "Miss Swiney argues that "man, on a lower plane, is undeveloped woman."" Because that's very likely a book I'm not apt to easily bump into."

|

|

| 03/12/2013 | page 187 | 49.0% |

"Also footnotes alerted me to the Contagious Disease Acts and feminist reaction - which was basically 'why aren't men examined too? Why focus on prostitutes only?' http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Contagio... Now adding more books to my list..."

|

|

| 03/12/2013 | page 189 | 50.0% |

"So far all the biographies I can find on Josephine Butler are paper books. I only wish for ebooks for immediate gratification, but I suppose I'll go to the 1800s era texts online. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Josephin..."

|

|

| 03/12/2013 | page 193 | 51.0% |

"Josephine Butler: "At the very base of the Acts lies the false and poisonous idea that women have 'nothing to do with this question,' and ought not to hear of it, much less meddle with it. ...I cannot forget the misery, the injustice and the outrage fallen upon women simply because we stood aside, when men felt our presence to be painful." [Having an Interior Cheering Section for this.]"

|

|

| 03/13/2013 | page 218 | 57.0% |

""The Women Writers Suffrage League was the brainchild of two young journalists, Cecily Hamilton and Bessie Hatton...with the object of obtaining "the Parliamentary Franchise for women on the same terms as it is, or may be, granted to men." " - There was also an actress' league "to make up and disguise the WSPU leadership in their hideouts from the police.""

|

|

| 03/13/2013 | page 219 | 57.0% |

""Like most of the women writers, Violet Hunt was less than eager to participate in the large protest marches that led to jail terms, hunger strikes, and the horrors of forcible feeding. She was excused by the Pankhursts on the grounds that she had to support an invalid mother, that staple furniture of the woman writer's home...""

|

|

| 03/13/2013 | page 234 | 61.0% |

""Most suffragettes, however, could not imagine that sexual revolution would take the form of female license rather than male chastity." - so they'd be really surprised to see what happened in the rest of the 1900s."

|

|

| 03/13/2013 | page 258 | 68.0% |

""[Dorothy] Richardson maintained that men and women used two different languages, or rather, the same language with different meanings. As might and Englishman and an American, "by every word they use men and women mean different things." ""

|

|

| 03/13/2013 | page 260 | 68.0% |

""The stream-of-consciousness technique (a term, incidentally, that Richardson deplored, and parodied as the "Shroud of Consciousness") was an effort to transcend the dilemma by presenting the multiplicity and variety of associations held simultaneously in the female mode of perception.""

|

|

| 03/13/2013 | page 265 | 70.0% |

""I think it is important to demystify the legend of Virginia Woolf. To borrow her own murderous imagery, a woman writer must kill the Angel in the House, that phantom of female perfection who stands in the way of freedom. For Charlotte Bronte and George Eliot, the Angel was Jane Austen. For the feminist novelists, it was George Eliot. For mid-twentieth-century novelists, the Angel is Woolf herself.""

|

|

| 03/13/2013 | page 265 | 70.0% |

"On Woolf: "...in wishing to make women independent of all that dailiness and bitterness, so that they might "escape a little from the common sitting-room and see human beings not always in their relation to each other but in relation to reality," she was advocating a strategic retreat, and not a victory; a denial of feeling, and not a mastery of it.""

|

|

| 03/13/2013 | page 305 | 80.0% |

""It is as natural for a character in a [Margaret] Drabble novel to gossip about nineteenth-century heroines as to discuss her own childhood; in fact, more so. Heroines rather reticent about their own sexuality will decided that "Emma got what she deserved in marrying Mr. Knightley. What can it have been like, in bed with Mr. Knightley?"""

|

|

| 03/13/2013 | page 313 | 82.0% |

""[Doris] Lessing herself will have to face the limits of her own fiction very soon, if civilization survives the 1970s, which she has predicted it will not." - surprise non-apocalypse!"

|

|

| 03/13/2013 | page 314 | 83.0% |

""There is a female voice that has rarely spoken for itself in the English novel - the voice of the shopgirl and the charwoman, the housewife and the barmaid. One possible effect of the [1970s era] women's movement might be the broadening of the class base from which women novelists have come.""

|

|

| 03/13/2013 | page 321 | 84.0% |

"Thanks to notes like this in the Biographical Appendix - under Laetitia Elizabeth Landon, last sentence: "Died under mysterious circumstances." - Am having to look up every other entry because I must know more than that! http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Laetitia..."

|

|

| 03/13/2013 | page 322 | 85.0% |

"There are a lot of women authors with really little biographical information in this period. Example: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Baroness..."

|

|

| 03/13/2013 | page 325 | 85.0% |

"Another example of little known author, and short bio: "Emma Robinson (1814-1890): Novelist. Born in London, daughter of a bookseller. Remained single. Went mad. First novel, Richelieu in Love (1844)." - and not in wikipedia. Book is here:http://archive.org/details/richelieui..."

|

|

| 03/13/2013 | page 328 | 86.0% |

"Annie French Hector: "Journalist, novelist. ....married in 1858, had four children. Published 41 novels after the death of her husband in 1875." http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Annie_Fr..."

|

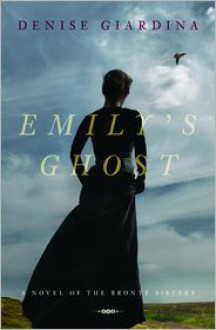

I LOVED THIS BOOK. It gave sort of insight to me re: the Bronte sisters, all of whom are in my top 10 of favorite authors (Charlotte-2;Emily-5;Anne-10). I went through and did more research on this novel though and the author actually had the story incorrect or took liberties, which is understood and happens. In my research, I found the parson actually had "feelings" for Anne.This was still an awesome read though and I will be seeking this author out again.

I LOVED THIS BOOK. It gave sort of insight to me re: the Bronte sisters, all of whom are in my top 10 of favorite authors (Charlotte-2;Emily-5;Anne-10). I went through and did more research on this novel though and the author actually had the story incorrect or took liberties, which is understood and happens. In my research, I found the parson actually had "feelings" for Anne.This was still an awesome read though and I will be seeking this author out again.