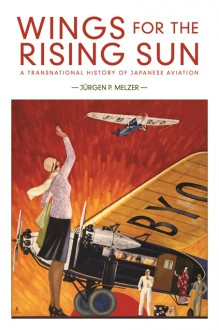

When the United States went to war against Japan in 1941, American pilots were shocked by the superior quality of the planes flown by their opponents. Believing that the Japanese were inferior technological copyists, the greater capability of many Japanese aircraft models quickly disabused them of their assumptions and forced them to adopt different tactics until American airplane manufacturers could catch up. In this book Jürgen Melzer examines how the Japanese exploited Western technological innovations and manufacturing processes to develop an aircraft industry that by the 1930s was in terms of quality the equal of any in the world, one that aided Japan's goals of empire-building through warfare.

Melzer begins his book by summarizing Japan's initial exploration of flight through the development of lighter-than-air craft. Here the role of the military and the "balloon fever" which gripped the Japanese foreshadowed developments when Japan turned to heavier-than-air flight after 1908. With Europe at the forefront of airplane by that point Japan sent two army officers there for training and purchased craft for them to fly upon their return as qualified pilots. Though Japan investigated air travel in a number of Western countries, for the first decade of development they relied mainly upon French training and purchases in establishing their air arm. Shifting priorities and disappointment with the poor quality of postwar French surplus led the Japanese government to turn to the Germans and the French after the First World War, as they sought both to exploit air power for naval warfare and to develop an indigenous aircraft industry.

While this effort created the later impression of the Japanese as technological mimics, Melzer details how the Japanese strove to limit their dependency upon Western manufacturers and know-how. This comes through especially in his description of Japan's interwar relationship with German airplane designers. Shackled by the Versailles treaty, German manufacturers were eager to develop export markets, with Japan among the most promising prospects. The Japanese particularly valued German innovations in all-metal planes, and worked to master their construction at a time when canvas planes were still the norm. While Germans such as Ernst Heinkel believed they could maintain a dependent relationship, by the mid-1930s Japanese designers had already caught up with German innovators, exploiting their ideas in new and innovative ways. So advanced was Japan's aircraft industry by then that during the Second World War they were able to develop rocket and jet engine technology with only halfhearted assistance from the Germans, only for their successes to come too late to reverse their imminent defeat.

Melzer's book offers readers a wide-ranging examination of how the Japanese exploited training and technology transfers to build a formidable industrial sector. In doing so, he provides a case study of how nations go from dependency to autonomy, if not in the end complete independence form outside influence. It's an interesting and well-argued analysis, one that will be of considerable interest to readers of aviation history, the history of technology, or of the Second World War and Japan's efforts to win it.

Log in with Facebook

Log in with Facebook