I first encountered Ravensbruck at age 10, when I read The Hiding Place, Corrie Ten Boom’s wartime memoir, for school. Although Corrie and her sister Betsie were not imprisoned in Ravensbrück for very long, the book made an instant and indelible impression on me; it’s partly or mostly responsible for the fact that I started to read everything I could about World War II.

A few years later, I read a biography of Mother Maria Skobtsova, the Russian Orthodox nun and French Resistance member who died in Ravensbrück in 1945. But after this, it really wasn’t until I read Elizabeth Wein’s wonderful Rose Under Fire that I heard about Ravensbrück again. It was the first time I discovered the story of the Polish Rabbits–the Lublin special transport who were experimented on in the camp–and it also gave me a sense that there were many more stories to be told.

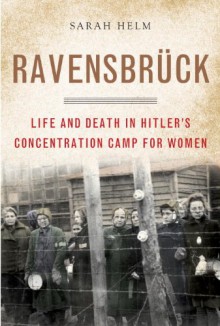

And now Sarah Helm has written a monumental book that has done just that. She began researching Ravensbrück after writing an earlier book about Vera Atkins, the SOE officer who spent the rest of her life trying to uncover the final fate of the SOE women she trained and sent into action. Four of those women died at Ravensbrück. It might have been easy to keep the focus there, to primarily tell the story of the English and American prisoners. But Helm does not do this. Included in the book are the stories and words of Polish, German, Russian, Ukrainian, Dutch, English, French, and Jewish women–and those are just the ones I’m remembering off the top of my head. She begins at the construction of the camp and continues on to show the ripples of its effect on the survivors after the war.

And I found that Helm does a marvelous job of keep the story on a human scale. When we begin to talk about 150,000 women prisoners, about 30-60,000 women killed, about the conditions and the medical experiments, it might easily become abstract, a kind of numerical problem. But we follow the stories of a few women at a time through the different periods in the camp, seeing how the conditions and decisions affect them. I found this way of storytelling so powerful, so intensely compelling, that I ended up reading this book very quickly, considering the length and subject.

Helm manages to let the voices of the survivors and victims–as well as the guards and other more culpable characters–come through, and at the same time she contextualizes them. She doesn’t shy away from presenting the circumstances of the account, the biases and self defenses of the witnesses, the questions we may never have the answers to. She is able to give an overview, to synthesize the different accounts and information to paint a picture, without denying the complexities of the situation and of the people involved–so many of whom could be both kind and unimaginably cruel.

One of the things I found most interesting were the accounts of resistance and sabotage, which were far more prevalent than I had realized. The workers in the various factories, at great personal risk, sabotaged parts for planes and bombs. Those who worked to sew clothing for German soldiers “often worked together, agreeing to destroy the finest fur by cutting it into tiny pieces, which they called poppy seed or macaroni…Others worked in groups of up to twelve, taking advice from veterans like Halina Choraznya, the Warsaw chemistry professor, who calculated how to give the anoraks special treatment by piercing the fur in such a way that it would fall apart.” Yet Helm also shows that with those acts of courage came a great price, and that this price was often demanded of others.

And yet, there were people like Halina Choraznya, who is described as “like a little mouse. Sitting there. A very strong little mouse. She organised everything,” who did act with great courage and resolve. And of course there is the amazing story of hiding the Rabbits, which appears in Rose Under Fire, and which is true. It really happened. The lights in the Appellplatz went out. We think of the people in the concentration camps as victims. But Helm (and others) show a much more complicated reality. In one sense, they were certainly victims of Nazi atrocities. But many of them also fought–in the camps, in ways small and large.

One of the major themes in Rose Under Fire is the phrase “tell the world”. It’s the motive Rose uses to keep going, and the burden she carries afterwards. What I did not realize is that, like the lights going out and the hidden Rabbits, it too is true. It occurs over and over again in the narratives of the survivors and witnesses, that same mixture of defiance and hope and responsibility. For instance: “A Norwegian prisoner told her rabbit friend that she would insist on being executed in her place. ‘You should be the one to tell the world about the crimes committed against you.'” And a prisoner who was briefly released “believed she had witnessed a monstrous crime in the making, and that she had been released by God to tell the world.” A quick Google Books search of the text turned up seventeen separate uses of the phrase, some in original testimony and some paraphrased.

It is perhaps the tragedy of Ravensbrück that the stories of the women who lived and fought and died and survived have been so forgotten, despite all their efforts. I hope that this amazing and heartbreaking book is another strike against that silence, another way to tell the world.

Log in with Facebook

Log in with Facebook