Imagine a world where the normal human life span is 150 years, where worn-out vital organs are routinely replaced by spares, where after death you will retain consciousness for eternity in cyberspace, where nanotechnology will enable you to transform a plastic bottle into a filet mignon for you...

show more

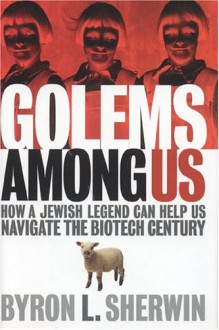

Imagine a world where the normal human life span is 150 years, where worn-out vital organs are routinely replaced by spares, where after death you will retain consciousness for eternity in cyberspace, where nanotechnology will enable you to transform a plastic bottle into a filet mignon for you to share with your android spouse. Scientists anticipate such a world within a century. Even now many signs of such biotech "progress" are with us. Accelerating developments in genomics, reproductive biotechnology, bionics, artificial life, genetic engineering, and related fields are compelling us to reexamine our most deeply held beliefs about ourselves and our world. As we do, the figure of Victor Frankenstein and the monster he created looms large: many people today see our predicament through the lens of the Frankenstein story, whose lesson is that humans should not "play God" or tinker with the toolbox of nature, at the risk of tragedy and catastrophe. Yet there is an available alternative both to the Frankenstein vision and to the ebullient enthusiasm of those who anticipate a riskless future. It is the most famous and influential post-biblical Jewish legend, the story of the golem―the creation of an anthropoid by mystical and magical means. Retold and embellished in twentieth-century literature, art, music, drama, film, science, technology, and popular culture, the golem legend has become a metaphor for our times, a resource for applying the wisdom of the past to the perplexities of the present and the challenges of the future. In Golems Among Us, Byron Sherwin briefly traces the fascinating history of the golem legend in Western culture, then shows what lessons it holds for us in navigating a safe journey―philosophically, theologically, ethically, and in public policy―through the minefield of social and biological engineering in which we now stand.

show less