We present here the text of the First Edition of Savitri with accent-marks; these are indicated with the font in red colour. The scansion of the lines could be left to the individual’s perception; but we should mention that we are not considering half-accents which on occasions can fall on vowels...

show more

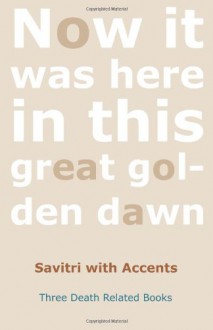

We present here the text of the First Edition of Savitri with accent-marks; these are indicated with the font in red colour. The scansion of the lines could be left to the individual’s perception; but we should mention that we are not considering half-accents which on occasions can fall on vowels in the rhythmic flow of the lines. It must also be noted that some accents could change from context to context, and from person to person. The subjective element in the rhythm must be recognised while reading or reciting poetry, principally the poetry of the mystic-spiritual kind where both inner sound and silence count the most. Let us take a few examples from the present set of three Books. Here is the first—Incrédulous of its tóó bríght hínts of héáven—which is pretty complex from the point of scanning with diverse types of feet, something which is unusual in Savitri. Among many variations the best could perhaps be: “Incréd|ulous| of its| tóó bríght hínts| of héáven|, with iamb-pyrrhic-pyrrhic-molossus-amphibrach making up the line desirably heavy and ponderous with the heavy non-belief of the mind when it comes across unfamiliar things that are too bright and beautiful for its immediate comprehension. In the “The wónderful, the chariotéér, the swíft” we have iamb-pyrrhic-pyrrhic-anapaest-iamb as if the movement giving speed to the chariot whose course cannot be prohibited or hedged by any power howsoever great or dark that might be; that power is Savitri’s God affirming himself just as forcefully in the pentametic verse. In contrast to these lines, we have in “In some pósitive Nón-Being’s púrposeless Vást” five most surprising anapaests leading gloom to worse gloom and death to emptier death. And here is an instance in which purposeful inversion helps settle the breaking of the line: “Hárdly can he hóld the gálloping hóóves of sénse”. Scansion-wise we can either have “Hárdly| can he hóld| the gál|loping hóóves| of sénse|” with trochee-anapaest-iamb-anapaest-iamb or “Hárdly can| he hóld| the gál|loping hóóves| of sénse|” with the dactyl-iambic beginning. Let us see this line without the inversion. “Hárdly he can hóld the gálloping hóóves of sénse”, which is there in the previous line, “Hárdly he can móúld the lífe’s rebéllious stúff”, the feet-repetition at the beginning in the two consecutive lines making them somewhat distasteful. While in both trochee-anapaest is natural, inversion in “Hárdly can he hóld” makes it explicit. The deft management of feet in both the lines indicates the quality of art in Savitri which actually comes from the inner sense of sound and the rhythmic surge and sweep as much as compression and intensity which we see in several situations. Of compression and strength we could have an example in “A húge inhúman Cyclopéan vóíce”, with iamb-iamb-pyrrhic-iamb-iamb. Let us take an example where each vowel has to be properly utilised: “Thy sóúl creátor of its fréer Láw” which scans as: “Thy sóúl| creá|tor of| its fré|er Láw| with a pyrrhic in the middle. And here are a few perfect iambic lines: “Abóve the strétch and bláze of cósmic Síght”; “The Míghty Móther síts in lúcent cálm”; “Our húman wórds can ónly shádow hér”; “Althóúgh he knéw refúsing stíll to knów”; Althóúgh he sáw refúsing stíll to séé”; “The twó oppósed each óther fáce to fáce”. But finally “The díre univérsal Shádow disappéáred”. We hope that the present attempt of bringing out the text with accent-marks will prove rewarding to the lovers of poetry, and in particular of Savitri in its metrical power, its rhythm and melody, its undertones and overtones, its volume and pitch and timbre, its nada and laya and chhanda, they carrying the “seed-sounds of the eternal Word”, they moving in the felicity of “rhythmic calm and joy”; possibly it would take us closer to the yogic source from which it originated.

show less