The Ivy Tree was published seven years into Mary Stewart’s career, in 1961, and in some ways it’s one of her strongest books. (Also one of my favorites.) It’s set in Northumberland, and weaves together some of the strands that Stewart returned to frequently. It’s an interesting one to reread, because the clues to the mystery are RIGHT THERE, I mean they are NOT HARD TO SPOT. And yet, the characters and their tangled relationships, and the vivid descriptions of the land and the farm are compelling enough that I didn’t even really mind. (Although I did notice.)

One of Stewart’s hallmarks is a well-read heroine, and she often opens with some sort of literary allusion. The Ivy Tree is no different–we start off with an old folk song for an epigraph and each chapter is headed with another bit of a folk song. There’s also a Shakespeare reference right on the first page.

But as I mentioned before, Stewart seems particularly fascinated by Jane Eyre and prone to include references in different ways. In Nine Coaches Waiting, it was the governess motif, but here it’s coming home to a burnt house (Thornfield/Forrest Hall) and an absent and scarred former lover. (Adam was even trying to save his wife, who had set a fire. I am not reading too much into this.)

She also includes hidden Roman ruins at least twice–here and in Touch Not the Cat. There seems to be a thread, at least in the English-set books, of the history of the landscape. The past is never that far from the present, whether it’s ancient, or more recent. In The Ivy Tree, family history is also important–it’s why Annabel left home, why Con makes the choices he does, and to a certain extent it’s why Annabel returns.

That’s the spoiler: Mary is totally Annabel. Now, it may be just because I read Brat Farrar again for last month’s series, but I kept wondering if Stewart was influenced by Tey at all. This story and Brat Farrar are kind of inverses of each other. Both main characters pretend to be someone they’re not. Brat pretends to be Patrick coming home; Annabel pretends that she is Mary Grey, but also that she is herself coming home. (This makes more sense in context.) I can’t say for sure, obviously, but regardless of Stewart’s intent, the echoes between the two are really interesting.

Now, to be fair, any mention of the Pennines is going to get me right away (thanks to both Code Name Verity and The Winter Prince). But also the opening of this book is just lovely: vivid descriptions of the landscape that somehow also give an instant sense of Mary/Annabel. There are other clues later in the book–her knowledge of Forrest Hall, of horse cant, of Adam–that give her away if you know what you’re looking for. I think, though, that the opening is where it starts. No stranger, however interested, could give such a detail and loving sense of the land.

And I do think that Stewart handles the emotional side of Annabel’s relationship to Whitescar and her family well. She’s playing a tricky game and we get to see just enough of it for the whole thing to work. I also liked the way Stewart uses Annabel’s cousin Julie as a foil, but also as someone that Annabel has an uncomplicated and warm relationship to. This can’t be said of any of the men in the picture, from Matthew right down to Con and Adam.

Stewart’s heroines have an unfortunate tendency to lose their backbone as soon as the romantic interest arrives. Annabel is really the least woolly of them all, in my opinion. She remains pretty self-reliant, although there are a few lapses into nonsense from time to time. And Adam, while not at all my cup of tea, is at least less annoying that Raoul. (Actually the man I like most in this one is Donald!) I did get a sense that there was a possibility of Adam and Annabel working through their past to a happy future together.

Still, for me the strengths of this one are much less the romance and much more Annabel’s common sense and strength. Combined with the texture of the family and landscape, it’s a story that I find quite compelling and enjoyable.

The Stars as Seen from This Particular Angle of Night: An Anthology of Speculative Verse - ,Carolyn Clink, et. al.

The Stars as Seen from This Particular Angle of Night: An Anthology of Speculative Verse - ,Carolyn Clink, et. al. How Like a God - Brenda W. Clough

How Like a God - Brenda W. Clough  The Magic School Bus at the Waterworks - Joanna Cole

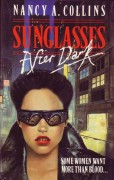

The Magic School Bus at the Waterworks - Joanna Cole Sunglasses After Dark - Nancy A. Collins

Sunglasses After Dark - Nancy A. Collins  The Enchantments of Flesh and Spirit - Storm Constantine

The Enchantments of Flesh and Spirit - Storm Constantine  Love and War - Tonya C. Cook, et. al.

Love and War - Tonya C. Cook, et. al. Mask Of The Wizard - Catherine Cooke

Mask Of The Wizard - Catherine Cooke

Log in with Facebook

Log in with Facebook