Over the past few years, the word "fascist" has been deployed increasingly to describe modern-day political movements in the United States, Hungary, Greece, and Italy, to name a few places. The word brings with it some of the most odious associations from the 20th century, namely Nazi Germany and the most devastating war in human history. Yet to what degree is the label appropriate and to what extent is it more melodramatic epithet than an appropriate description?

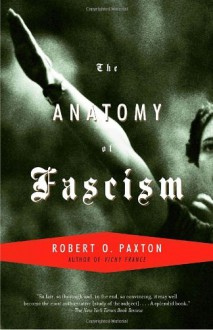

It was in part to answer that question that I picked up a copy of Robert O. Paxton's book. As a longtime historian of 20th century France and author of a seminal work on the Vichy regime, he brings a perspective to the question that is not predominantly Italian or German. This shows in the narrative, as his work uses fascist movements in nearly every European country to draw out commonalities that explain the fascist phenomenon. As he demonstrates, fascism can be traced as far back as the 1880s, with elements of it proposed by authors and politicians across Europe in order to mobilize the growing population of voters (thanks to new measures of enfranchisement) to causes other than communism. Until then, it was assumed by nearly everyone that such voters would be automatic supporters for socialist movements. Fascism proposed a different appeal, one based around nationalist elements which socialism ostensibly rejected.

Despite this, fascism remained undeveloped until it emerged in Italy in the aftermath of the First World War. This gave Benito Mussolini and his comrades a flexibility in crafting an appeal that won over the established elites in Italian politics and society. From this emerged a pattern that Paxton identifies in the emergence of fascism in both Italy and later in Germany, which was their acceptance by existing leaders as a precondition for power. Contrary to the myth of Mussolini's "March on Rome," nowhere did fascism take over by seizing power; instead they were offered it by conservative politicians as a solution to political turmoil and the threatened emergence of a radical left-wing alternative. It was the absence of an alternative on the right which led to the acceptance of fascism; where such alternatives (of a more traditional right-authoritarian variety) existed, fascism remained on the fringes. The nature of their ascent into power also defined the regimes that emerged, which were characterized by tension between fascists and more traditional conservatives, and often proved to be far less revolutionary in practice than their rhetoric promised.

Paxton's analysis is buttressed by a sure command of his subject. He ranges widely over the era, comparing and contrasting national groups in a way that allows him to come up an overarching analysis of it as a movement. All of this leads him to this final definition:

Fascism may be defined as a form of political behavior marked by obsessive preoccupation with community decline, humiliation, or victimhood and by compensatory cults of unity, energy, and purity, in which a mass-based party of committed nationalist militants, working in uneasy but effective collaboration with traditional elites, abandons democratic liberties and pursues with redemptive violence and without ethical or legal restraints goals of internal cleansing and external expansion. (p. 218)

While elements of this are certainly present today, they are hardly unique to fascism and exist in various forms across the political spectrum. Just as important, as Paxton demonstrates, is the context: one in which existing institutions are so distrusted or discredited that the broader population is willing to sit by and watch as they are compromised, bypassed, or dismantled in the name of achieving fascism's goals. Paxton's arguments here, made a decade before Donald Trump first embarked on his candidacy, are as true now as they were then. Reading them helped me to appreciate better the challenge of fascism, both in interwar Europe and in our world today. Everyone seeking to understand it would do well to start with this perceptive and well-argued book.

Log in with Facebook

Log in with Facebook