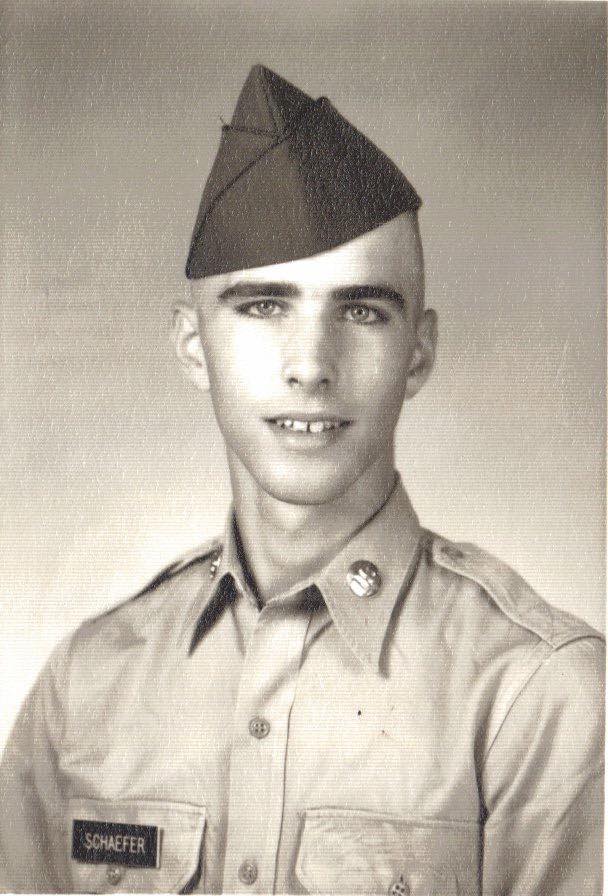

I met Steve Schaefer in the early years of this decade because of our shared association with Pillars of Honor, a Chicago-based organization dedicated to giving a day of honor to World War II veterans too weak to take their Honor Flight. After my husband and I opened each program with World War II songs, Steve, the Pillars of Honor president, would give a few remarks, always introducing himself as a Vietnam veteran, the son of a World War II veteran.

It didn’t take long to connect the dots: Steve’s service had been inspired by his dad’s. And the younger Schaefer was every inch the elder had been, serving three tours in Vietnam and earning four Purple Hearts.

War has always produced heroes, a fact understood by young men of all time. Jurate Kazickas, a combat reporter who witnessed young Americans come under fire in Vietnam, wrote: “War, for all its brutality and horror, nevertheless offered men an opportunity like no other to be fearless and brave, to be selfless, to be a hero.” (1) Like Steve, many of the young men Kazickas met had been inspired by the heroism of the previous generation.

Those fighting on the other side were infused with their own historical perspective. When the Viet Minh defeated the French at Dien Bien Phu in 1954, they were hailed as national heroes. So it was hardly surprising that the Viet Minh remaining in the south after the civil war began were quickly given a new name by their enemies: Viet Cong, short for Viet Nam Cong San, the Vietnamese Communists. Vietnamese soldiers working for the southern government would be hard pressed to fight with any enthusiasm against the Viet Minh, their own Greatest Generation.

But if war provides an opportunity for heroism, it also, of necessity inflicts wounds. Viet Cong fighters and soldiers of the North Vietnamese Army were patched up by Communist medics in the south who were constantly on the run, changing locations almost as often as they changed bandages. One of these, surgeon Dang Thuy Tram, was moved to give her fallen patients poetic tribute in her diary: “Oh, Bon, your blood has crimsoned our native land. . . . Your heart has stopped so that the heart of the nation can beat forever.” (2)

Thuy and the American nurses featured in my book, Courageous Women of the Vietnam War, couldn’t help becoming emotionally attached to their patients, who, even if they had joined up to become heroes, were reduced to mere boys when wounded. Years after his hospitalization in Vietnam, Air Cavalry Sergeant Robert McCance wrote a note of thanks to his nurse, Anne Koch, acknowledging that he had then “really needed the touch of a mother’s hand.” (3)

Female medics on both sides of the conflict gave that motherly touch. But as Lynda van Devanter, US Army nurse in Vietnam wrote later, “Holding the hand of one dying boy could age a person ten years. Holding dozens of hands could thrust a person past senility in a matter of weeks.” (4)

Anne Koch.

The war wounded these healers. Thuy was killed before it ended. Most of the American nurses survived but suffered decades of inner pain, which matched, or perhaps in some cases outstripped, the outward suffering of their broken, bleeding, dying patients, images that were often etched permanently in the nurses’ minds.

After the war, the eerie silence between the two enemies once locked in mortal combat represented oceans of hurt; all attempts to move past the war seemed hollow when veterans on both sides were suffering. The southern Vietnamese soldiers were given absolutely nothing except, in many instances, a one-way ticket to a cruel reeducation camp. If they were fortunate enough to emerge alive, mere shadows of their former selves, they saw that the new government had obliterated all memorials to their dead comrades.

Post-war life was also bitter for the victors. The rumored riches in the south had been exaggerated and the new country’s economy disastrously unable to provide for its people, much less its fighters. Many female veterans hoped that victory would bring an opportunity to raise a family in peace. But the long, grueling years of war left too many unable to bear children even if they could find someone amid the surviving males to marry them.

Most American female veterans went on to live outwardly normal lives but they, like their male counterparts, received no recognition for many years. This was, perhaps Steve Schaefer’s biggest wound and one that should have earned him—and all the other vets—an additional Purple heart. The inability of family and friends to comprehend what they had experienced, on the one hand, and the lack of respect from strangers on the other, exacerbated the inner pain overwhelming these veterans.

But perhaps the most inspiring stories of the Vietnam War occurred at this point. While post-traumatic stress is as old as combat, the suffering of Vietnam veterans gave it a name. A brotherhood of the war-wounded was formed and, as my book illustrates, a sisterhood as well. Lynda van Devanter founded the Women’s Project at the Vietnam Veteran’s of America. Kay Bauer, a US Navy nurse who was targeted by domestic terrorists after the war, created a PTSD program for female Vietnam veterans in Minneapolis, her hometown. And Diane Carlson Evans, who wrote my book’s forward, spearheaded the difficult ten-year project to honor all the women veterans of the war with their own memorial in Washington, D.C. The unveiling of that memorial on November 11, 1993, was a time of honor, personal healing, and numerous reunions between female medics and their patients.

Many Vietnam veterans, male and female, would eventually succumb to the effects of Agent Orange. Steve Schaefer was one of these. But like so many veterans of that war, Steve had found a way to move forward in his life long before it ended. He led local veteran’s associations and helped the homeless for decades, and in his final years worked tirelessly to give tribute to the generation that had inspired him.

- Courageous Women of the Vietnam War, 89.

- Courageous Women of the Vietnam War, 129.

- Courageous Women of the Vietnam War, 119.

- Courageous Women of the Vietnam War, 145.

Top photo: Jurate Kazickas.

Bottom photos, left to right: Dang Thuy Tram, Bobbi Hovis, Lynda van Devanter, Kay Bauer.

Log in with Facebook

Log in with Facebook