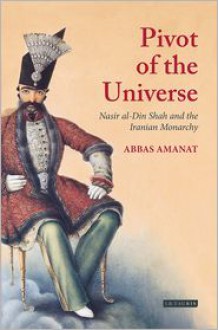

For the Qajar dynasty of Iran, the mid-nineteenth century was a period of considerable challenge. Though they had succeeded in securing their claim to the throne, their rule was but a pale shadow of the monarchy that had dominated the region during Safavid times. Domestically their regime grappled with unrest and westernizing pressures, while internationally they found themselves a pawn in the geopolitical struggle between the Western empires of Britain and Russia. These challenges dominated the reign of Nasir al-Din Shah, who ruled over Iran for nearly half a century. Though his reign has long been the subject of considerable study, with this book Abbas Amanat has provided the first biography in English of Nasir, offering a detailed study of his life and times.

Yet Amanat's book is not a full accounting of Nasir's life. His focus is on the shah's early years and the first twenty-three years of his lengthy reign. These he sees as critical years in the evolution of the institution of the Iranian monarchy, as it abandoned many of its medieval institutions and developed into a more modern absolutist monarchy. This was not without considerable struggle, nor did it begin with Nasir himself. By the early nineteenth century, the Qajars committed themselves to the notion of primogeniture as a means of determining succession, yet Nasir's path to the throne was plagued with potential challengers from within his family. His successful accession was due in part to the sounds advice of Amir Nizam, who soon afterwards became Nasir's chief minister. Yet his time in power was short, and Nizam's dismissal (and subsequent execution) represented the end of his efforts to institute a range of modernizing reforms. This Amanat sees as a tragically missed opportunity, as the shah rejected any further efforts to resume them as he was unwilling to accept the diminution of his power that they entailed.

Nizam was replaced by Mirza Aqa Khan Nuri, who proved more accommodating to the shah's whims. During this period, which lasted for about a decade, Iran gradually drifted from a slightly pro-British orientation towards a more active opposition to their presence. Here Amanat's extensive use of British diplomatic archival resources is fully evident, allowing him to present a richly nuanced picture of Iran's relations with the British Empire. This growing tension, exacerbated by Nasir's expansionist ambitions, ultimately led to a brief war, one that resulted in a humiliating defeat for the monarchy. Nasir accepted the reality of the situation, and shifted his focus towards solidifying his power. Amanat is good here at describing the clash between Nizam and Nasir's wife Jayram, a clash that resulted in Nizam's dismissal. With his departure, Nasir effectively abandoned the position, establishing instead a more direct rule where the major departments of government answered directly to the shah. Yet his subsequent efforts to implement a more moderate of reform failed, Amanat argues, because of his unwillingness to develop a more systematic form of government, which would have forced him to surrender some of the authority he held most dear.

Extensively researched and incisively written, Amanat's book provides valuable understanding of Nasir and his reign. Though based on a considerable command of published works and documents in the British archives, he never lets the details overwhelm his narrative or overshadow his analysis. Apart from a poor job of editing, the book's main flaw is a lack of comparable detail on the Russian side of the diplomatic divide, which would have helped to provide a more well-rounded picture of events. Yet this does not detract from his overall success in illuminating for readers a fascinating tale of a monarchy in transition. With only a single chapter summarizing the remaining quarter century of Nasir's reign, it is hoped that at some point Amanat gives these years the same rewarding attention he did to the ones covered in this excellent book.

Log in with Facebook

Log in with Facebook