We don't need the destruction of entire cities to know what it's like to survive a catastrophe. Whenever we lose someone we love deeply we experience the end of the world as we know it. The central idea of the story is not merely that the apocalypse is coming, but that it's coming for you. And there's nothing you can do about it.

Dale Bailey, "The End of the World As We Know It"

The reason I like apocalyptic fiction so much is that it is, in fact, fiction. A half-dozen pre-human mass extinctions notwithstanding, the real world has never actually ended. And so, for me, apocalyptic stories are always metaphors - for loneliness and isolation, for fear of the future, for the possibilities of new beginnings, for first-world guilt, for community and cooperation, for homesickness, for grief, for loss, for thanatos and the destructive impulse. All things which I have experienced. All things which make apocalyptic stories - so bizarre and shocking and unfathomable on the surface - deeply resonant for me.

That all evaporates when it's no longer fiction. If I were to say I "related" to a book about a nuclear catastrophe which killed and continues to kill uncountable hundreds of humans, animals, plants, and ecosystems, which rendered a quarter of an entire country uninhabitable for the foreseeable future, which destroyed lives beyond repair, which crippled an empire... if I, well-fed and cozy here in my middle-class American apartment, were to say I could relate to that, I'd be an ass. Worse than an ass.

And yet.

There is a poem I never wrote called "The Eruption of Mt. Baker", which was part of a poetry collection I also never wrote called Separation Anxiety. I am not a poet, or not a good one, which is why this was never actually written, but several years back I spent a lot of time writing drafts and then ripping them up. It was based on a recurring nightmare I used to have: We're driving away from home for the last time - I'm ten years old, and I'm sitting in the back of my parents' minivan, playing this handheld electronic baseball game. We're moving 2500 miles away, but I can't even be bothered to look out the window at our house, our neighborhood, our town, our state for the last time, even though I know we'll never come back. Never in the next few years, anyway, which for a 10-year-old might as well be forever. This part isn't a dream. It's the morning of June 22, 1994, and it's almost unbearably sunny.

In the dream, this is all the same, except the mountain, Mt. Baker, is erupting as we're driving away, the ash and molten lava covering everything up behind us as we go, and the flow is following us, chasing us, as we calmly drive away, never more than a few feet behind the car. Still, I never look up from the game. My dad is whistling in the driver's seat. Everything I ever knew is being destroyed, but none of us even notice. We never turn around.

Of course, we've been back since then. I live only about 100 miles away now, and it's not such a big deal to drive up there if I ever feel the need. But it's hard to go home these days, and it keeps getting harder - as the things I remember change or disappear, as the people get older and drift away, as it becomes less and less recognizable as home, only this place that meant everything to me once, and is now just a graveyard for painful memories.

My parents and little brother were in town over the holidays this year, and along with my sister, the five of us drove up there to see some old friends. But as soon as the scenery along the highway changed from generic to imbued, I started to get queasy again. Because it's not enough to go back to the place - home isn't just a place. It's a place and a time, and we're 17 years too late now. 17 and a half. It just keeps getting further and further away, and there's no way back, anymore.

Another poem in the nonexistent collection was going to be called "The Excavation of Everson", where I went home years later and began chipping away the layers of volcanic rock, to find the town perfectly preserved within, Pompeii-like, with tiny hollow molds in the shape of my ten-year-old friends. Hollow human molds of my family, my siblings, and me, still there. Still there. Somehow, despite everything that had happened in the intervening years, we had never really left at all.

I don't know why this fantasy appealed to me so much. Everything perfectly preserved, but dead. But I would just picture myself sitting in my old bedroom again, everything the way I remembered it. The sun in the perfect sky, coming in through the window, blazing like it did on June 22, 1994. And I'd find that little handheld game, wherever I used to keep it. And I'd smash it into tiny pieces.

We are all prisoners of time, and we all lose our homes, our pasts, the people we love, and eventually ourselves. Bit by bit, the things we remember go away. The world is always ending, it's just usually so slow and subtle we never notice until we're forced to: a move, a rite of passage, a birth, a death.

A war. An attack. A revolution. A nuclear catastrophe. An apocalypse.

This is why I read fiction about the end of the world.

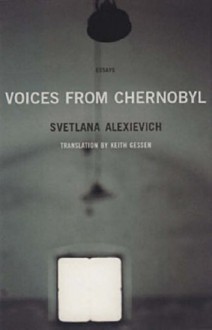

What happened at Chernobyl is real, and so unlike the other apocalyptic books I've read, I can't appropriate it as a metaphor for my own life. What these people went through is ghastly and unimaginable, and it's the result of an inept and corrupt government. It could have been prevented. It could have been mitigated. This book should be read, because what happened to these people should not be swept under the rug, as the Russian government has tried to do for over 25 years. We have a responsibility to hear their stories, to know what really happened, to keep it from happening again.

And as for me, I know that imagining events in my own life as if they were the result of a natural disaster is trite. It's cheap. It's adolescent hyperbole. I can go home whenever I want - there is no lava, there is no radiation.

And yet.

In Ukraine and Belarus, many people returned to their irradiated homes shortly after the disaster. Many never left. They moved back into their houses, they began to farm the earth. Living there is a death sentence, and they know it. They could leave, but they don't.

Why would they do this? I can't really know, and I can't really relate to their reasons. It was a different time, a different culture, a different set of values.

And yet.

"Even if it's poisoned with radiation, it's still my home. There's no place else they need us. Even a bird loves its nest . . ."

"During the day we lived in the new place, and at night we lived at home - in our dreams."

"I washed the house, bleached the stove. You need to leave some bread on the table and some salt, a little plate and three spoons. As many spoons as there are souls in the house. All so we could come back."

Monologues by Those Who Returned

2 January 2012

Log in with Facebook

Log in with Facebook