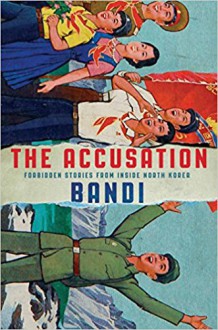

This is a collection of short stories criticizing the North Korean government. Purportedly, it was written by an anonymous North Korean official still living in the country, and smuggled out as a handwritten manuscript. Upon reading the first couple of stories, though, I began to wonder if that backstory is a publicity stunt. I’ve read a lot of contemporary English-language fiction, and a lot of fiction from countries around the world, and what struck me about this collection is that it is written in a style characteristic of modern English-speaking authors. This makes it easy reading for those audiences: it’s written with the immediacy and emotional intimacy with the characters that one typically sees in English-language fiction; it has that pleasing balance of dialogue and narrative, that easy-to-read plot-driven flow, that immersion in the characters’ thoughts and feelings that characterizes most popular fiction today. Authors from cultural traditions very different from the mainstream western ones rarely write this way unless they have immigrated to an English-speaking country, even though almost all of them would have ready access to popular fiction, unlike someone living in North Korea.

Having these doubts, I poked around on the Internet for more information about the book (the New Yorker article is worth a read). No one has proven it to be a hoax, and a vocabulary analysis apparently indicates that the writer used North Korean language, which has diverged somewhat from South Korea’s over the decades of separation. However, I found it significant that journalist Barbara Demick, author of the fantastic Nothing to Envy (a nonfiction narrative of life in North Korea, based on her research and defectors’ accounts) also doubts the official version. Her doubt seems to stem primarily from the author’s keen awareness of the regime’s internal contradictions; this is apparently an understanding that takes defectors significant time outside the country to fully comprehend.

As for the book itself, each of its seven stories is a quick and easy read, though they average around 30 pages each. However, after the first two or three stories, which were fairly enjoyable, I began to tire of their incessant drumbeat. All of the stories are about how the regime and life in North Korea crushes a character in one way or another (usually metaphorically, but in one case physically): there is no conflict that doesn’t have the Party at its base and no possibility of happiness. At the end of the final story, a character, gazing at the red-brick local Party office, reflects, “How many noble lives had been lost to its poison! The root of all human misfortunate and suffering was that red European specter that the [party official] had boasted had put down roots in this land, the seed of that red mushroom!” Perhaps I ought to take the idea that the government could be the cause of all human suffering as evidence that the author does in fact live in North Korea, but in any case, such a simplistic view of the world doesn’t make for high-quality literary work.

Whoever the author may be, the fundamental storytelling skills are certainly there, despite a singular political focus, and it will be an especially interesting book for those who haven’t read much about North Korea. But for those who want to learn more about the country, I recommend starting with the brilliant Nothing to Envy.

Log in with Facebook

Log in with Facebook