Two months short of his 46th birthday, on November 25, 1970, Yukio Mishima with a handful of followers and dressed in full uniform, entered the compound of the Japan Self-Defense Force, gagged and tied up the commander of the JSDF, demanding the assembly of the entire Eastern division ( a gathering of 800 soldiers) to listen to his planned speech: "

an appeal to repudiate the post war democracy that robbed Japan of its identity; to restore Japan to her true form, and in the restoration, die."

When his speech went unheard, muffled by the noise of his audience's jeers, Mishima engaged his final bloody concept,

seppuku. His "second" then completed the ritual by beheading him with a long sword. The sequence of events played out dramatically and undeniably like something out of a violent motion picture.

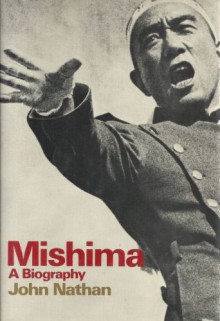

Biographer John Nathan knew Mishima professionally and personally, having translated

The Sailor Who Fell From Grace With The Sea. His analysis of Mishima's private life and novels led him to believe that his suicide was primarily about his erotic lifelong fascination with death. Mishima wanted passionately to die all his life, and consciously chose "patriotism" as a means to his fantasized, painful "heroic" end.

Mishima was born on January 14, 1925, and birth-named Kimitake Hiraoka (Yukio Mishima would become his pen name). At only 50 days old, his paternal grandmother Natsu Nagai took him away from his mother, Shizue, and moved him into her dark room downstairs of the family home. Natsu was noble born, a highly unstable woman who suffered fits of hysteria as a child. She held Kimitake "prisoner" until he was 12 years old, jealously and fiercely guarding him. She kept rigid control over his upbringing until 1937, when she became too ill to take care of him, paving the way for him finally to live in his parents' household. Nathan insightfully suggests that she possibly hoped to ingrain in her first grandchild the values she believed were the birthright of the noble Nagai.

Natsu exposed Kimitake to Kabuki theatre, and might have contributed in this way to his creative development: taking him to his first play,

Chushingura--the Tale of the 47 Ronin --a celebration of feudal allegiance, said to be the most exciting of the great Kabuki classics. Nathan also alludes to her afflicting this impressionable young boy with constant mournful lamentations of a "

lost distant past, an elegant past, a past beauty," fueling a romantic longing for "

purity and beauty and a fierce impossible desire to be other than himself."A loner and rarely seen without a book, Kimitake spent time writing poetry and fantasy stories as young as 12 years old, reading works by Oscar Wilde, Rilke, and Tanizaki. His adolescent writing sensibilities were influenced by the Japan Romantics, evolved with an aesthetic formula in which "

Beauty, Ecstasy and Death are equivalent." Later, his ideology became ultranationalistic, exalting traditional convictions "worthy of dying for."

Nathan submits Kimitake's latent homosexuality was unintentionally the result of the hostile domestic environment he grew up in, however, this

notion that a person's sexual preference is a product of living in a dysfunctional environment

did not sit well with me - that's a whole 'nother debate! As young as 16, he showed anxiety and disgust at what he sensed was an "unwholesomeness," apologizing for his

masquerade of normalcy. This is later reflected in the novel that catapulted him to stardom-

Confessions of a Mask.

In Februrary 1945, Mishima welcomed the draft into the army, but when Japan surrendered on August 15, and the Emperor called for his subjects to lay down their arms, Mishima, Nathan assumes, might have convulsed with the "existential horror" of being cheated and deprived of that morbid destiny, gleaning from his postwar essays and novels: "

The war ended. All I was thinking about, as I listened to the Imperial Rescript announcing the surrender, was the Golden temple. The bond between the temple and myself had been severed. I thought now I shall return to a state in which I exist on one side and beauty on the other. A state which will never improve so long as the world endures."Mishima found it difficult adapting to postwar reality in the atmosphere of labeling, blacklisting and enforced isolation of "literary war criminals." It was the older, established writers who were being sought and many routes were closed to getting his manuscripts sponsored. His first novel,

Thieves, was violently lyrical and in spite of a glowing preface by his new mentor, Yasunari Kawabata, the novel was ignored. Even with some guidance and editing, his stories went unnoticed and "

no one who mattered was impressed."

The autobiographical novel

Confessions of a Mask, was a book he felt he must write in order to survive. It was a therapeutic effort, a process of self-discovery for Mishima, who finally validated within himself a suppressed homosexuality, and who was incapable of feeling alive or of showing passion, except in sadomasochistic fantasies which stank of blood and death. "

This book is the last testament I want to leave behind in the domain of death where I have resided until now."

His decision to join the Army Self Defense Force (ASDF) in 1967 was partly for patriotic concern, and partly to feed his need for glory - of the hero, not the writer. In his mind, he had taken his first step in becoming a warrior, a samurai- a persona he obsessed over.

"

The samurai's profession is the business of death. No matter how peaceful the age in which he lives, death is the basis of all his action. The moment he fears and avoids death he is no longer a samurai."Rumors of a nomination for the Nobel prize ( for the third time) buzzed around Mishima in 1968. However, the prize went to his old mentor, Yasunari Kawabata. Many close to Mishima suspected this disappointment about the Nobel prize had a significant impact on his decision to end his life.

Mishima was a man who felt less real in this world than in the realm of his poetry and novels; a deeply tortured man who yearned for his eroticized, violently lyrical literary work to be acknowledged; but his brutal, unheard last words were the veritable final blow. Clearly, he was more suited to the bygone feudal days of Japan-- an accomplished swordsman loyal to the empire, who grabbed at the romantic hero's painful death he had longed for all his life. Nathan thoroughly probed Mishima's psyche through his novels; his conclusions into this tragic life lead him to hope finally that "

he found what he expected to find inside and beyond the pain."Shizue, his mother, summed it up best at his memorial, "

Be happy for him.. This was the first time in his life Kimitake did something he always wanted to do."

Log in with Facebook

Log in with Facebook