When I think about Bruno Schulz' life story, I always feel a pang in my heart. I'm known for my displays of pity regarding every living being, even trees (several nights ago, after a big storm, I found a young tree that was bent and was probably going to be cut down; I felt so sorry for it that went out, straightened it and tied it). So it's no surprise that the unjust death of Schulz and the disappearance of his other writing provokes a dull ache in my heart, especially after having an insight into his wonderful mind, through

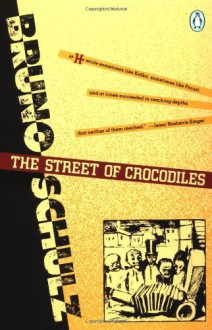

The Street of Crocodiles.

Reading about him, I've found out that he had no apparent influence from other writers. He lived in Drogobych all his life, being a recluse; he worked as a teacher of drawing and had a few friends, who had no idea of his literary aspirations. It was a lucky chance that one of his pen friends encouraged him to write - it was in these letters that his stories were shaped.

When Bruno Schulz's stories were reissued in Poland in 1957, translated into French and German, and acclaimed everywhere by a new generation of readers to whom he was unknown, attempts were made to place his oeuvre in the mainstream of Polish literature, to find affinities, derivations, to explain him in terms of one literary theory or another. The task is well nigh impossible. He was a solitary man, living apart, filled with his dreams, with memories of his childhood, with an intense, formidable inner life, a painter's imagination, a sensuality and responsiveness to physical stimuli which most probably could find satisfaction only in artistic creation — a volcano, smoldering silently in the isolation of a sleepy provincial town.

He must have had access to some unearthly world, full of rich wonderful things, that we, normal mortals, don't have the chance to get a glimpse of, other than through the writing of Bruno Schulz and gifted writers like him.

Reading

The Street of Crocodiles was like having a brain orgasm: its rich metaphors were incessantly uplifting, its words caressed my mind without ever pausing. I was constantly marveling at the poetry of Schulz' prose. This could get tiring at times, because his stories never let me breath and slack, but kept requiring my ever-present attention. The task was made even more difficult because I've read the English translation and bumped into a lot of words that I didn't know, far more than in any other book I've read so far.

After tidying up, Adela would plunge the rooms into semidarkness by drawing down the linen blinds. All colors immediately fell an octave lower, the room filled with shadows, as if it had sunk to the bottom of the sea and the light was reflected in mirrors of green water — and the heat of the day began to breathe on the blinds as they stirred slightly in their daydreams. [...] Everyone in this golden day wore that grimace of heat — as if the sun had forced his worshipers to wear identical masks of gold.

Bruno Schulz is drawing inspiration from his childhood, but his writing leaves the reality at some point and wanders into imagination, blossoming into an explosion of smells and rich imagery. In the center of the stories lies Schulz' father, an almost surreal character, who gradually acquires the traits of a mythological being, wandering freely from reality into the fantastical realm. It reminded me of Danilo Kiš' [b:Garden, Ashes|217984|Garden, Ashes|Danilo Kiš|http://d.gr-assets.com/books/1347934698s/217984.jpg|211053], where the father was also the central, elusive figure.

Bruno's father is shaped as an eccentric, an almost lunatic, constantly taking an interest in peculiar things, such as the long-forgotten rooms where mold and dust had settled, creating a throbbing world that disappears the moment one opens the door. Or the tailor's dummy that is not simply an object, but

imprisoned matter, tortured matter which does not know what it is and why it is, nor where the gesture may lead that has been imposed on it for ever. He is disgusted but also fascinated by cockroaches, imitating them to the point of becoming one (this is one of his resemblances to Kafka - [b:The Metamorphosis|485894|The Metamorphosis|Franz Kafka|http://d.gr-assets.com/books/1359061917s/485894.jpg|2373750] - although some critics say that Schulz was not actually inspired by the first).

The father is presented on the brink of immediate death, but he always resurfaces with renewed energy, captivating the house once more, disturbing the peace and quiet with his follies. He is the antidote for boredom, in those days that

hardened with cold and boredom like last year's loaves of bread. One began to cut them with blunt knives without appetite, with a lazy indifference.At some point, the child is even convinced that his father had metamorphosed into a stuffed condor, echoing the absolutely gorgeous recount of the latter's passion for exotic birds, which were raised in the attic - one of my favorite parts of the book.

Not only the father, but also the outer world is presented in a poetic manner, bordering on surreal: the rooms with their shape-shifting wallpapers, the garden with lush vegetation, the end-of-the-world storm, the family shop with oceans and rivers of cloth, the cardboard town from the Street of Crocodiles, the alluring Cinnamon Shops. Everything in this book is a feast of senses and I don't have enough words to praise it.

Perhaps the city and the marketplace had ceased to exist, and the gale and the night had surrounded our house with dark stage props and some machinery to imitate the howling, whistling and groaning... We were increasingly inclined to think that the gale was only an invention of the night, a poor representation on a confined stage of the tragic immensity, the cosmic homelessness and loneliness of the wind.

You should definitely read

The Street of Crocodiles, it is truly a literary gem.

Log in with Facebook

Log in with Facebook