Tarzan of the Apes by Edgar Rice Burroughs

This book was a lot of fun, however you will not be surprised to learn that it is marred by horrible racism toward Africans. Things that might surprise you about the world of Tarzan:

- apes have fangs

- apes eat lots of big game

- Tarzan had an innate sensibility that stopped him from eating humans

- although Tarzan could not speak, having been raised by apes, he learned to read and write English by looking at books

Tarzan fell in love with Jane, and rescued her (and everyone else in her party) from terrible danger, and behaved like a complete gentleman to her. He left her love notes, however she did not understand that they were from him, since she did not know he could read and write. Then Tarzan found someone to teach him to speak. Unfortunately he was taught to speak French! His one aim was to go to Baltimore where Jane was, and on the way he learned to eat cooked food with a knife and fork, speak English, etc. He arrived just in the nick of time to rescue Jane from a terrible fire. Unfortunately Jane had just gotten engaged to be married to another guy because she and her father were broke, but Tarzan threatened the guy into breaking the engagement, and Tarzan also gave Jane and her father a big treasure chest of gold. Then Jane decided that although she loved Tarzan, she’d better marry someone else because Tarzan was too wild. When Tarzan proposed, Jane realized she wanted to marry him after all but she’s just agreed to marry Tarzan’s cousin. Then Tarzan got the result of his fingerprint analysis (don’t ask) that proved he was the real Lord Greystoke. But since Jane was going to marry the supposed Lord Greystoke, Tarzan nobly suppressed this information, and told people that he was the son of a human woman and an ape. I know I’ve focused a lot on Jane, but this book was mostly swinging on ropes and adventure and killing and other good clean fun.

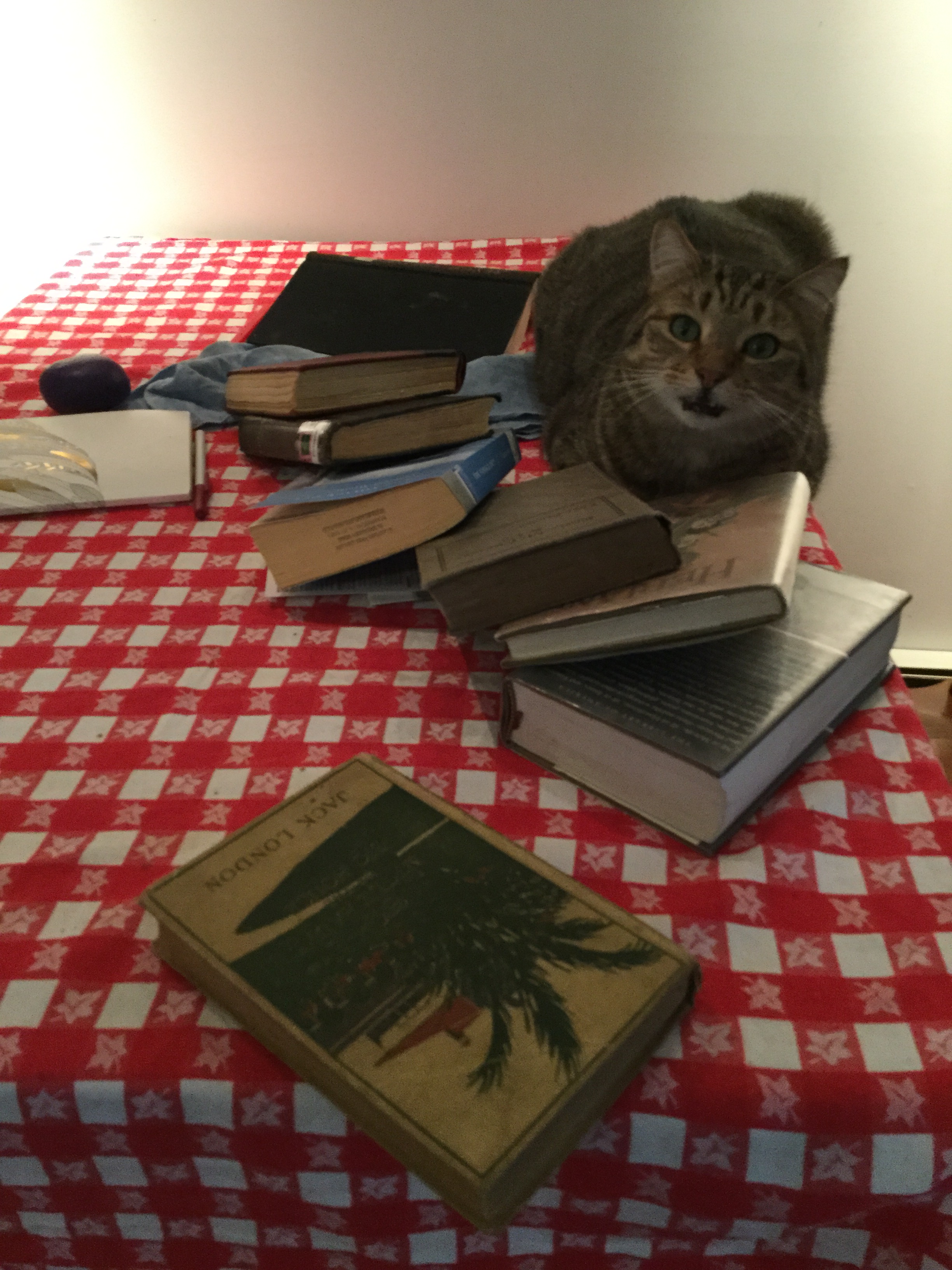

These two covers are surprisingly similar, yes?

The Titan by Theodore Dreiser

I really enjoyed Dreiser’s other books Sister Carrie and Jennie Gerhardt, but didn’t like this one so much. I’m only now learning that this is a sequel to a previous book, which makes me feel kind of stupid. It’s about a man named Cowperwood who wants to become really rich and successful. At the opening of the book, he’s just getting out of the penitentiary for stock exchange fraud or something along that line. His mistress Aileen has been waiting for him. He moves to Chicago, divorces his wife, marries Aileen, and makes a ton of money by hook or by crook buying up the streetcar system and other concerns. The financial/political part was not very appealing to me but that’s just a matter of taste. The one element that was interesting to me was how much homo-eroticism plays into business and finance in this book. All these different men meet Cowperwood and are magnetised by how handsome and charismatic and commanding he is, and they end up supporting him in his schemes. The back of the book promises that his every triumph will become a hollow defeat, but they read as hollow to me all the way through.

Cowperwood cheats on Aileen with a lot of different women, but the one he is really in love with he has known since she was a teen, which is pretty gross. Aileen is angry and decides she will cheat too to get back at Cowperwood and picks out an idle society man. When she invites the man to her house, he date rapes her. They end up “having an affair,” but Cowperwood doesn’t care. Aileen is also disappointed that she’s not a social success. Cowperwood was a pretty unlikeable character.

Even though the Enneagram (a personality typing system) is not really my thing, I couldn’t help seeing Cowperwood as a 3 with a 4 wing (because all he cares about is status and success, but he has an artistic side.) So I kept trying to picture him as David Bowie, a legendary 3 with a 4 wing, to make myself like him more, but it didn’t work. At the end of the book, Aileen slits her wrists and Cowperwood stops her and scolds her. He resolves to avoid her as much as possible in the future and decides that she won’t try again. I feel Dreiser’s female characters are more real and easier to relate to, which is probably why I enjoyed those other two books. So you can imagine how surprised I was to read in the afterword that Cowperwood was very similar to Dreiser himself and that Dreiser’s women characters are “unconvincing.” My other complaint about this book is that there are one million minor characters and they all have funny names. But I have to take my hat off to Dreiser for not being a racist as so many other writers of 1914 are. He has a couple of Jewish characters who speak with an accent, but not offensively so, and they are no more money-grubbing than every other single character in the book.

Booklikes has a really strange search engine. Why would it only link to a copy of this book that has a weird picture on the cover of Dutch men from the wrong century? This is a better cover!

The Ragged-Trousered Philanthropists by Robert Tressell

This book, the exact opposite of The Titan, was completed in 1910 but published posthumously, as the Irish author died of TB at the age of 40 a year later. It’s an unabashedly socialist novel that follows the lives of a group of English working men. They earn poverty wages and live in constant fear of being unemployed. While a lot of conditions described in the book seem as true of the working poor today as a century ago, the one striking difference is that there was no safety net whatsoever. If the men were out of work for too long, they and their families would literally starve to death, and the only alternative was going to the workhouse, which is not really described in this novel but seems to be feared as an equivalent fate to death. The most harrowing part is when one of men believes he should murder his wife and bright young son and then himself to spare them a worse fate, and is mulling over the best way to do it. That was Stephen King-level horror. There are a lot of long speeches about socialism that are meritorious but boring and I ended up skimming through them. It was mostly this one guy Owen making the speeches, but the other men dismissed him as a nut. I think this book deserves its status as a classic.

Arcadian Adventures With The Idle Rich by Steven Leacock

Satirical short story collection about the lives of the American upper class. I enjoyed this one. I think my favorite story was about a pretend guru who gathers bored rich women to learn his “oriental” wisdom and then makes off with their jewelry. Or maybe it was the one about the great financial genius who turns out to be a country man who knows nothing and just struck it rich by accident and just wishes he could get back to his old home.

The Last War (also known as The World Set Free) by H.G. Wells

The most notable thing about this sf novel is that in 1914 Wells predicted atomic energy and atomic warfare. It’s too bad no one heeded his warning. In fact it seems his ideas inspired the scientists who worked on the atom bomb. This is the only book of 1914 I encountered that admitted the possibility of a war that would kill millions, even as such a war got underway. This book doesn’t have a plot or main characters in a traditional way. It’s a history book from the future, and the first chapter (the “prelude”) covers actual history. The rest of the book covers the development of atomic power which essentially creates free energy that destroys the world economy, and then atomic war destroys all the major cities, killing everyone and leaving a radioactive landscape. However, after that the book becomes remarkably upbeat as the survivors create a world government that unifies the planet. You get snapshots of life from different people throughout the book. Other than a kind of dismissive attitude toward India, this book isn’t even racist. The edition I read had an actually interesting introduction, by Greg Bear, comparing Henry James and Wells, who were frenemies. Bear says that this was the moment when speculative fiction and literary fiction parted ways. Spec fic (along with my bff Arnold Bennett) was dismissed as trying to get people to believe in something and too action/plot oriented. Literary fiction was elevated for being sexless, bloodless, and more about money and people’s inner lives than stuff happening. Bear puts forward the non-dual POV that there’s no reason these two styles had to be opposed to each other. Anyway, I thought it was notable that this was one of the few books of 1914 that has been reprinted by a reputable press with attention paid to the book design—because actual normal humans might want to read this book.

Our Mr. Wrenn: The Romantic Adventures of a Gentle Man by Sinclair Lewis

This was Sinclair Lewis’ first published book for grown-ups. It was about a milquetoast kind of guy who lives not far from where I grew up in NYC who quits his job and travels to Europe looking for adventure. But he’s actually a pretty bourgeois guy so he doesn’t want too much adventure. He meets a young bohemian woman who seemed just like the kind of unreliable bright young thing you would still meet today. She was probably my favorite part of the book because she was so vivid and realistic. But when Mr. Wrenn gets back to NYC it seems to him that he’d be better off with a more normal young lady—like this nice girl he’s just met. The downfall of this book: racism. I did enjoy it when I read it but it was strangely forgettable. I brought it on a trip with me thinking I hadn’t read it yet and I was dumbfounded when I opened it up and realized I’d just read it a few weeks earlier. But what’s to blame here, the book? Or the lack of cover art? Or my demented mind?

Delia Blanchflower by Mrs. Humphrey Ward

I enjoyed Mrs. Ward’s 1913 offering, but this anti-suffragette novel was hard to take. The eponymous character is a rich, beautiful, and charismatic young woman whose father has just died. But instead of inheriting her fortune outright, she’s been saddled with a guardian/trustee because her dying father correctly believed that she would devote all her money and all her to life to the cause of woman’s suffrage if she had control. Of course the guardian is a magnificent unmarried middle-aged man who is handsome, noble, etc etc, and sparks fly between him and Delia Blanchflower. Delia is under the sway of an unscrupulous older suffragette. They live together and are devoted to each other. Although it’s explained that the older woman only wants Delia’s money for the cause and doesn’t really care about her, she appears to get jealous of the guardian and basically cuts Delia off. There was a lot of stuff about how their group was blowing up mailboxes, which seemed ridiculous to me, but it turns out that suffragettes really did blow up mailboxes. One woman complains about how her former servant was sick and dying and wrote a letter to her, but it was blown up, so the servant died thinking her mistress didn’t care about her. (I learned from this book that the most important part of noblesse oblige is taking care of your servants when they’re sick.)

There are a number of anti-suffrage women role model characters in the book, and also a woman who believe that women should get the vote, but she doesn’t care if it’s in her lifetime or her daughter’s lifetime or neither, and that it’s wrong for women to do anything except patiently wait for the vote. The stuff that these women say makes absolutely no sense and reminds me of the stuff that people say today that makes absolutely no sense. It’s not about content, it’s about being dignified and an upstanding member of society. People just want everything to be comfy and pleasant. Anyway, there’s a beautiful old historic home that the suffragettes want to blow up (I’m assuming this is based on Lloyd George’s home that really was bombed) and in the end even though Delia and her guardian try to prevent it, the wicked suffragette lady sets it on fire, killing a little disabled girl who has no function in this book other than to be sacrificed—and the suffragette lady dies too. Is this book racist? Of course. Here’s a sample line: “From her face and figure the half savage, or Asiatic note, present in the physiognomy and complexions of her brothers and sisters, was entirely absent.”

Personality Plus by Edna Ferber

This was the most disappointing book of 1914 for me. I really loved Roast Beef Medium last year and this is the sequel. But I could tell Edna was just phoning it in. It’s about Emma McChesney’s son going into the advertising industry and triumphing. But you can tell Edna Ferber didn’t know anything about the advertising industry so there’s a curious lack of substance to it. It’s okay, Edna, I still believe in you! I see there’s another sequel next year and I bet that one is going to be great!

Penrod by Booth Tarkington

I read most of this. It’s fairly funny, about a little boy who gets into different scrapes. Think Otis Spofford. But it’s also pervasively racist, with many casual racial epithets for African-Americans, and talk of “Congo man eaters.” I got to a part where Penrod makes friends with three African-American brothers. One has a speech impediment, one is missing a finger, and I forget what was the deal with the third brother. Penrod decides he’s going to open a freak show starring the three brothers. I just couldn’t take it anymore and brought the book back to the library. I think the fact that it’s a children’s book is what makes it the most awful.

Revolt of the Angels by Anatole France

I only made it through a couple chapters of this book before I ran out of time. It seems good so far. No angels have appeared yet. It’s just some family history and a description of a library. Speaking of libraries, this book is not due back at the library for another two weeks so we’ll see how I do.

Log in with Facebook

Log in with Facebook

![The Ragged Trousered Philanthropists Volume I [Easyread Comfort Edition] - Robert Tressell The Ragged Trousered Philanthropists Volume I [Easyread Comfort Edition] - Robert Tressell](http://booklikes.com/photo/max/220/330/upload/books/4/5/457a1381fbb29d8e3d5692d3a6e240e2.jpg)