Disclaimer: ARC via Cambridge University Press and Netgalley. Read in exchange for a fair review.

I have some deal breakers when it comes to the books I read. I am not fond, sometimes even hate, books where the eldest sibling is by default the bad one. I am fond of wives being blamed for their husbands porking anything that moves. I judge Shakespeare biographies by how the writer treats Anne Hathaway.

No, you fool, not the actress.

Shakespeare’s wife.

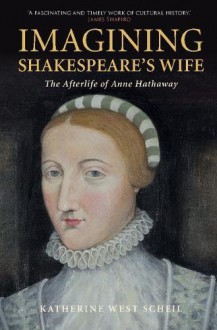

A few years, Germaine Greer published Shakespeare’s Wife, a biography/study of Anne Hathaway. In large part, Greer’s book seemed to be a rebuttal to Stephen Greenblatt’s harsh attack on Hathaway in his Will in the World. Katherine West Scheil’s book, Imagining Shakespeare’s Wife, also takes Greenblatt to task, but Scheil’s purpose to look at how the image or reputation of Shakespeare’s wife reflects on the period in which a work is published.

While Scheil does seem partial to Anne, the beginning of the book, dealing with the known facts of Hathaway’s life is fair. Scheil remembers that there is no way we can do for sure what exactly happened between the Shakespeares. She presents the facts, she presents the debates, but she keeps her view out and lets the reader reach a decision, if the reader wants to. The rest of the book deals largely with how people at various times have viewed Anne Hathaway. As Scheil notes, many times writers have made their Anne Hathaway as opposed to writing about the real Hathaway.

This starts, in part, Scheil notes with the romance of the Anne Hathaway Cottage – which, to be frank, you can understand the romance part because it is absolutely beautiful. Scheil notes that the one time owner and tour guide of the house, Mary Baker, had connections to the Hathaways and was, in part, making sure of her family’s connection to the Bard of Avon. My guess is that Mary Baker was getting a bit pissed off about all the people standing on Anne Hathaway’s grave to get a better look at her husbands. Taking about wiping their feet on the woman.

ON the other hand, Scheil notes that the anti-Anne venom was set by Malone whose biography of Shakespeare was one of the earliest. She even ties Malone’s view of Anne to his proving the Ireland forgeries as fakes. We then tour other early biographies and fictional accounts, all of which even the non-fiction, seem to be proto-fanfiction if not outright fanfiction.

The analysis is best when looking at recent authors, though she doesn’t fully account Peter Ackroyd’s unwillingness to admit to certain sexual misconduct on the part of his heroes – she acknowledges Ackroyd’s seeming blindness of a sexual relationship between the Shakespeares before marriage as willful disregard of the time of their daughter’s birth, but Ackroyd also contorts himself in regards to Dickens extra-marital life as well. Scheil doesn’t pull punches, and if you, like me, were luke- warm to Greenblatt, Scheil aims and hits torpedoes at him.

Hence I love her.

It is a bit of surprise that Greer’s book doesn’t get more coverage. The response, in many cases unfair and overly harsh, is noted, but Scheil gives little speculation why – is it due to sexism or how someone suggest that Hathaway might have been worthy (or over worthy) of our Shakespeare? Additionally, she doesn’t ponders some of the more reaching claims of Greer, which also fall into the realm of this book. Greer’s book is a must read, but surely some of her conclusions were also influenced by feminist views. It seems strange not to discuss this year.

The most horrifying aspect of the back is the discussion of the modern historical romance novels and movies (such as Shakespeare in Love). This is not because of Scheil’s writing, but of some of the response of readers and movie viewers as well as the writers who have a tendency to either write Anne of as Shrew who deserves to have her husband cheat on her (common) to an Anne who embodies the traditional good wife that young female reader should aim to be (less common). There is some hope, though. Scheil covers more recent works that are fairer to Anne in terms of fiction. Her book about Hathaway will also add to your must read shelf, if you are a Shakespeare fan.

Considering the mutability of Shakespeare the man, it is hardly surprising that Anne Hathaway has become a channel on which writers sail their version of Shakespeare – family man, unhappy husband, child of nature. It is too Scheil’s credit that while she presents and discusses these myriad Annes, she always keeps the reader aware of the true Anne, the one who we cannot know, who is impossible to know, but who deserves to be acknowledged simply because she is human.

Highly recommended.

Log in with Facebook

Log in with Facebook