Less than a year ago I reviewed a novel by Catalan author Mercè Rodoreda (1908-1983) who is much celebrated in her country but virtually unknown elsewhere. I was so impressed by the book that I felt like reading also others of her works and from the two novels published posthumously, both of them unfinished, I eventually picked the one available in English translation, namely Death in Spring or in the original Catalan La mort i la primavera, i.e. Death and Spring. At first the title seems a bit strange, if not contradictory because it links death with nature’s rebirth after winter, but given that the novel flows over with powerful as well as poetical symbols and metaphors of life and death it’s quite appropriate. It’s a complex and well-constructed story about society that reminds me a lot of the works of Franz Kafka although it’s different in style.

The nameless I-narrator and protagonist makes his first appearance as a fourteen-year-old boy who enters the river passing under his mountain village built generations earlier on the debris of a huge rock-slip. He inhales the beauty of nature surrounding him and realises that he is “being followed by a bee, as well as by the stench of manure and the honey scent of blooming wisteria” representing the village with its pink houses that is always on his mind. As it turns out people there have many rituals to keep misfortune at bay. On the other side of the river is the forest of the dead with a tree dedicated to every inhabitant living or already dead with a plaque and a ring. During funerals all children are locked away into the stifling wooden kitchen cupboards, a custom that clearly mirrors the cruel death ritual practiced by the villagers for generations that requires to force pink cement down the throats of the dying in order to keep their souls from escaping and turning into shadows creeping “among the shrubs, always threatening to attack the village”. At the same time, and less obviously, it reflects the oppressive atmosphere in the village where everybody has to follow strict rules and not even the children are allowed to breathe freely in the literal as well as in the figurative sense. For being a boy the narrator doesn’t understand why the man whom he watches from behind a shrub hollows out a tree and enters it to die. As it turns out the man is his father, but instead of showing himself and talking to him, the boy returns to the village and tells the blacksmith. Everybody rushes out to give the already half-dead father the necessary cement treatment. With his teenage stepmother whom everybody considers retarded and strange he roams the village and its surroundings by night taking fun in vandalising the forest of the dead and using the pink powder of the cave to find out where its waters flow – thus defying the old village rituals that don’t make sense to them. Before long their adolescent urges take over and they have a daughter, but the community doesn’t accept them neither as individuals nor as a family because they are just too different, too free, too alive…

Many reviewers argue that Death in Spring represents life during the Spanish Civil War and in the rigid regime of General Franco that followed and that forced the author into exile, but in my opinion this is too limited an interpretation. I think that the author more generally portrayed the workings of human society where conservative forces use to be the stronger ones except in times of deepest discontent and misery. Even in our modern western civilisation that holds individual freedom in such high esteem, those who aren’t like all others or behave in a different, maybe even revolutionary way are marginalised, excluded and eventually crushed, i.e. driven to suicide or madness like in the novel although more subtly than in a totalitarian regime. In a nutshell: this is another great work of literature that would deserve much more attention. Highly recommended!

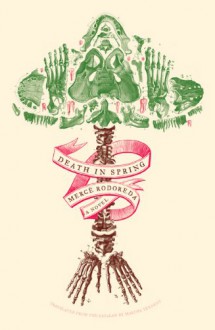

Death in Spring - Mercè Rodoreda,Martha Tennent

»»» read also my review of In Diamond Square by Mercè Rodoreda.

Log in with Facebook

Log in with Facebook