The Brave Adventures of Lapitch by Ivana Brlic-Mazuranic

A sweet, lovely children’s book about a cobbler’s apprentice who leaves his abusive master and sets out to seek his fortune, having many adventures along the way. As the story explains, Lapitch is cheerful as a bird, brave as a knight, as wise as a book, and as good as the sun. I can see why this is a Croatian classic.

Wet Magic by E. Nesbit

A family of brothers and sisters and the urchin they befriend encounter a mermaid who brings them to a magical underwater kingdom. My favorite part was the first half, set in our regular world. I noticed a bunch of reviewers on Goodreads saying the same. Considering that E. Nesbit was a radical Marxist, I was surprised by her obsession with royalty and how much better they are than anyone else. There was a part where the children had to fight storybook legends who were on the side of evil. The storybook legends had no power if the children didn’t know them, so I would have been super-helpful in this fight because I’d never heard of any of them. All the storybook legends were male except for a generic horde of Amazons. Trite racist trope: boy stolen by gypsies. Otherwise charming.

The Flirt by Booth Tarkington

In possibly one of the earliest examples of a movie tie-in, the copy I read was a 1931 reprint containing photos from the movie version. (The Bad Sister was based on The Flirt and is notable for being Bette Davis’ screen debut, with a minor role for Humphrey Bogart. What’s hilarious is that not only do the movie characters have different names than the characters in the book, nothing portrayed in the movie photos happens in the book at all.) This novel has that classic device of two sisters, one good and one thoroughly bad. The bad sister uses her feminine wiles to steal all the men and get everything she wants. There’s also a kid brother, who was my favorite character because he sees through everyone, plus he’s a bully who then gets bullied himself. I also enjoyed the witty, doomed, alcoholic character Richard Lindley and the con man character. The bad sister has to be punished at the end, which is kind of a downer. There was no room in 1913 for a woman to be anything but a saintly pushover. Other than that, a fun read. Downfall: racism against a stereotypical manservant character.

The Custom of the Country by Edith Wharton

Undine Spragg, a vain, self-involved woman from some hick town, climbs the social ladder, oblivious to the body count she leaves along the way. I probably would have enjoyed this book more if I hadn’t just read The Flirt, which has a similar plot and theme but is more light-hearted. Other than Undine’s son, there weren’t really any characters I felt sympathy with. Edith Wharton is a great writer but I just felt vaguely oppressed while reading this one.

When William Came by Saki

I didn’t enjoy Saki’s 1911 offering, so I was going to skip this one, until I read the plot description and realized it was speculative fiction. This novel is set in a world where Germany has conquered Britain! This fascinated me, and it was clear that Saki was the only writer who saw World War I coming, so I had to read it.

Saki’s prose is witty and crisp; here’s an example: “Plarsey had never been able to relinquish the idea that a youthful charm and comeliness still centered in his person, and labored daily at his toilet with the devotion that a hopelessly lost cause is so often able to inspire. He babbled incessantly about himself in short, neat, complacent sentences, and in a voice that Ronald Storre said reminded one of a fat bishop blessing a butter-making competition.” It’s Saki’s usual satire of high society, except this time his aim is to roast England for being insufficiently militaristic. The idea is that soft Britain was completely caught off guard and was unable to defend itself against a German invasion.

All the spec fic elements are great, especially his descriptions of how the German overlords changed the public parks in London. (They spruce up Hyde Park but add tacky public art, like a statue of Alice in Wonderland, just like what we have in NYC.) Saki foresaw the Hitler Youth phenomenon by a couple of decades with his description of Germany’s attempt to win over the young people via the Boy Scouts. You have to read the book to find out if this works or not. All the British aristocrats are lazy and muddle-headed and just want to go on with their lives as usual even though their country has been annexed. There are two main characters, a husband and wife. The wife, Cicely, is a beautiful woman who only cares about her own pleasure, very similar to many other female characters in the books of 1913. Her husband, Yeovil, is very worked up about the fait accompli, which is what they call the take-over, but may be lulled into apathy by the delights of upper class British country life (hunting and riding and other outdoorsy things.)

The downfall of this book is the same as last time: anti-Semitism. Cecily is going to have a piano player visit, and her husband asks, “Not long-haired and Semitic or Tcheque or anything of that sort?” “There are even more [Jews] now than there used to be,” says another character. “I am to a great extent a disliker of Jews. . .” It’s very hard to picture German society as a haven for Jews, but that is how Saki imagines it. There aren’t really a lot of charcters in this story that I could sympathize with.

Weirdly, the book that this one most reminded me of is Heinlein’s Starship Troopers, because they both have the same wacky message that the key to civic virtue is military service.

Also, this is the book of 1913 that has the second-most porn-y name, after Wet Magic.

Roast Beef Medium by Edna Thurber

This novel is about a middle-aged, divorced traveling saleswoman named Emma McChesney and the prejudice and hardship she faces. She earns “a man’s salary” and supports her teenaged son. The book was absolutely fascinating as a document of sexism in 1913. Thurber wanted to get into controversial topics but had to talk around them, so sometimes I was baffled as to what was going on, but eventually everything would become clear. (I think.) For example, there was one part where I thought the main character Emma was befriending a drag queen but it turned out instead the woman was a stripper. (This makes me sound really thick, but all the talk about “I’m not a real woman” and working in a special club for men only was confusing. And there’s a lot of mystifying period slang.)

I cannot tell if Edna Thurber really believed that housewifery and marriage were the only things that could fulfill a woman, or if she felt (perhaps rightly) that it was obligatory to throw that kind of sentiment over a book that’s about a strong single woman with a career. Reading this book was actually a bit painful because of the unending sexual harrassment Emma faced. It was of a very sanitized “let me take you out to dinner because you’re so beautiful” kind, but I still found it upsetting. Weirdly, this book reminded me of the Lad: A Dog series by Albert Payson Terhune because they both have the same thing happening over and over: Lad/Emma meets someone who is prejudiced against him/her, but then Lad/Emma proves him/herself through incredible heroism and nobleness, and the person realizes how wonderful s/he is. Couldn’t Emma just once meet someone who didn’t make all kinds of assumptions about her, and why did she have to educate these sleazebags over and over? It was just depressing, but I think hyper-realistic.

Here’s a description of Emma and her best friend. “Theirs was not a talking friendship. It was a thing of depth and understanding, like the friendship between two men.” Hate yourself much? But then, “They sat looking into each other’s eyes, and down beyond, where the soul holds forth. And because what each saw there was beautiful and sightly they were seized with shyness such as two men feel when they love each other, so they awkwardly endeavored to cover up their shyness with words.” Oh, I see, so it’s like that kind of friendship between men.

I looked at Edna Ferber’s Wikipedia page and it seems a lot of people think she was gay, but there’s no evidence she ever had a romantic or sexual relationship with anyone, so a lot of other people think there’s no basis for that assumption. I am equally compelled by both points of view, especially based on the passage above. On the one hand, it seems obvious that a woman who never had any attachment with a man was a lesbian and just kept it on the DL; practically everyone I know is gay so why not Edna Ferber? On the other hand, maybe she was ace and just wanted to gaze into someone’s eyes, but people can’t conceive of that as possible so they are unfairly stuffing her into the gay category. Either way, Edna Ferber was not your average bear, and this book reads as very “coded” but I can’t quite crack the code.

O Pioneers! by Willa Cather

I read this in college and remember almost nothing about it, other than it was about immigrant agricultural workers and it was kind of a downer. I remember liking it. Thank Heavens I went to college, huh? I learned so much! There’s also controversy about whether Willa Cather was a lesbian but I think this time it’s an open-and-shut case.

Laddie by Gene Stratton-Porter

Narrated by the youngest child, this novel depicts growing up in a large family in the country as alternately idyllic and horrifying (although clearly Stratton-Porter thought it was all awesome.) The good: playing unsupervised outdoors all day, having adventures and learning all about flora and fauna. The bad: playing unsupervised outdoors all day, so one older brother tries to hang her to see what it’s like, she tries to kill a ram, she and the same brother feed a goose until it splits open and dies. This dichotemy seems incredibly realistic to me and reminded me of my girlfriend’s account of her childhood in County Clare. The teacher hits the main character across the face on her first day and her brother tells her it was her own fault and to keep quiet about it; again, this seemed like searing realism. At first the main character feels unwanted and unloved because her mother didn’t want to have another child, but her brother Laddie of the title is her champion and truly cares about her, and by the end of the book so does the rest of the family. There’s a romance between Laddie and a neighbor girl, and a lot of religious content that was completely mystifying to me. I thought it was forward-thinking for the mom to say that women should have their own money.

The Valley of The Moon by Jack London

I haven’t read that much Jack London and I thought he only wrote nature stories about wolves and people dying in the snow. So this novel took me by surprise, especially the social commentary on working class life. The story is about a factory girl named Saxon who falls in love with a teamster/former prizefighter named Billy. Life is hard, the teamsters’ strikes keep getting busted, the cops are shooting strikers, and all the stress is driving Billy to drink and be brutal to Saxon. But just when it’s all looking bleak, they decide to drop out of city life (I think they’re in Oakland) and go on the road in search of their dreams and a peaceful place to live sustainably, and everything changes for them. It kind of reminded me of Steinbeck, with a bit more muscular prose style. It was really interesting to read about these rural farm places in California that I know are today very populated. The downfall: anti-immigrant sentiment and racial slurs.

The Golden Road by L.M. Montgomery

I read the previous book in this two-book series (The Story Girl) two years ago for the books of 1911, but I had forgotten the characters and never really caught up to speed. It’s about a group of children who are friends, one of whom is the narrator. The narration was weirdly Jamesian (complicated, obfuscating) and actually kind of made me think of books with a group narrator like The Virgin Suicides—not what you expect for a children’s book. It didn’t help that two of the children are named Sara—I know there were fewer names a century ago, but still. My favorite parts were a case of mistaken identity in which the children thought a visitor was deaf but she wasn’t; when they were forced to stay overnight with a witch; and when their cat went missing. The children wrote a newspaper about their doings, which was a tiny bit boring. I felt there was an over-reliance on the children accidentally using the wrong product with disastrous results, in baking and so forth. This device was so effective in Anne of Green Gables when Anne dyed her hair green and got her best friend drunk but has now gotten a bit over-done. I think L.M. Montgomery was a bit bored by the book too, because at the end almost all the characters had moved away or were soon to die of consumption, so there’s no possibility of a sequel except in fan fiction. The nicest thing about this novel was its depiction of the last days of childhood and how precious it is when you can actually see it about to slip away from you. Overall I would recommend the Anne or Emily books before this one.

Totem und Taboo by Sigmund Freud

DNF. When I saw that the subtitle was “Some Points of Agreement between the Mental Lives of Savages and Neurotics,” I had a pretty good sense that this book was going to be awful. But I wanted to give it a fair shot. On page one of Chapter One (“The Horrors of Incest”), I read, “I shall select as the basis of comparison the tribes which have been described by anthropologists as the most backward and miserable of savages, the aborigines of Australia.” At that point I just gave it up as a lost cause. I flipped through the rest and basically his point is that psychologically people in traditional societies are just like children. I think in general the non-fiction of a century ago is not going to stand up as well as the fiction. I do grant this book the third most porn-y name, which seems only right.

What did I miss from 1913?

I had to bring these books back to the library, overdue and unread.

Pollyanna by Eleanor H. Porter

The Return of Tarzan by Edgar Rice Burroughs

I really do plan to read these and there’s nothing to stop me, because I bought them. When I do, I’ll write reviews.

The Conquest by Oscar Micheaux

The Third Miss Symons by F.M Mayor

The Regent by Arnold Bennett

Hagar by Mary Johnston

Children of the Age by Knut Hamsun

The Sequence by Elinor Glyn

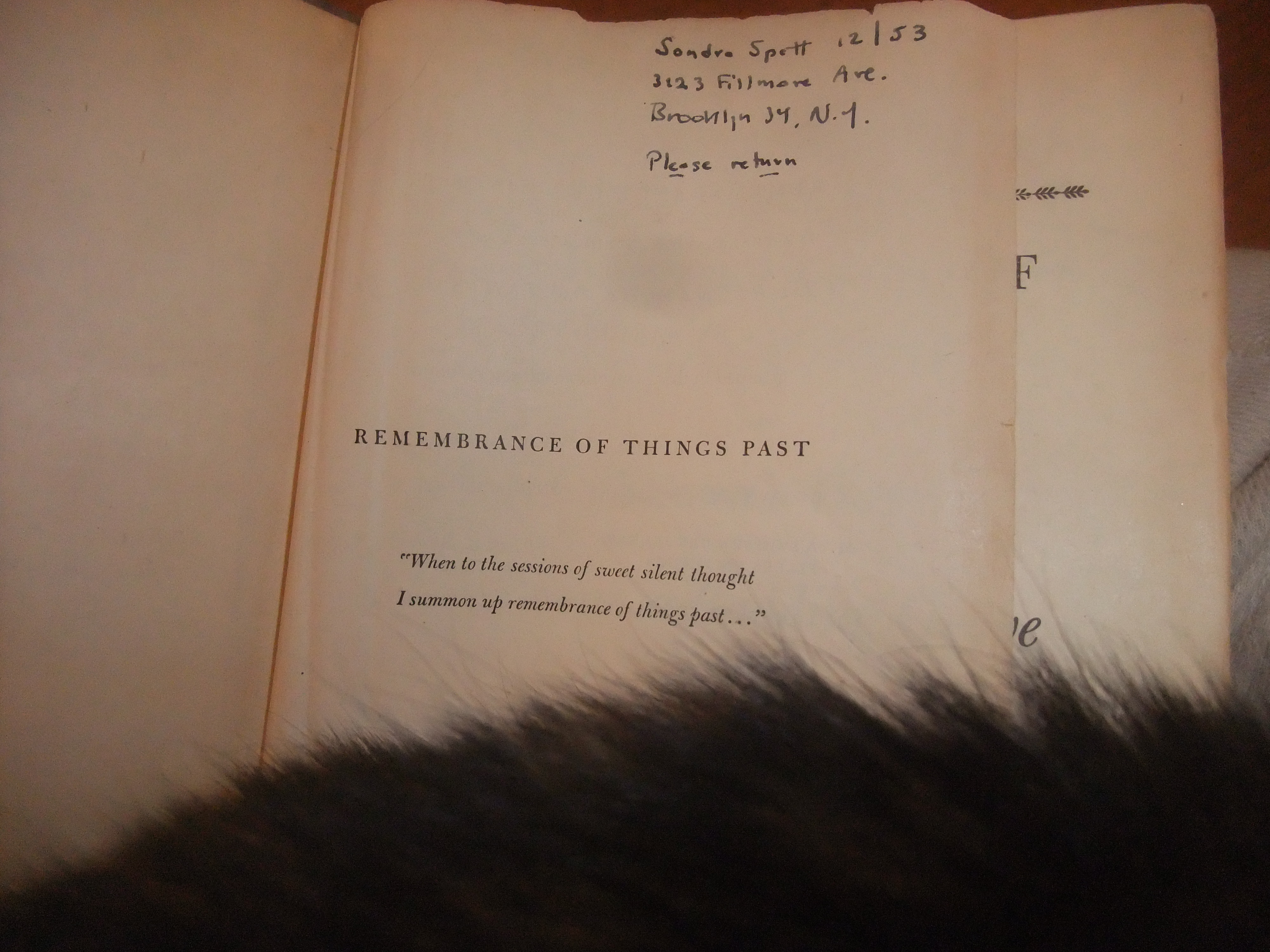

I just inherited Swann's Way by Marcel Proust from my mom but this is not the right time in my life for me this book. This copy was given to my mom in 1953 by her friend Ilse. They must have been high school seniors at the time. My mom told me she and Ilse sent postcards back and forth keeping each other updated on their progress through the book.

To learn about more books of 1913, visit the Wikipedia page.

Best of 1813

Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen

Well, I’m not sure if I’ve read any of the other novels of 1813, but I am confident that this is the most enduring novel of 1913 and the one with the most movie adaptations and spoof versions.

Best of 2113

The Martianess of Islington by Fortescue Imamu-Cottingforth

Literary trends are cyclical, and the books of 2113 have so much in common with the books of 1913. The novel takes place in 2100, just a few years after the advent of eternal life and free energy on planet Earth. Emblior, a Martian immigrant aged three hundred, lives alone, humbly and happily, in a tiny compartment in London. Everyone relies on her but she is first in no one’s heart. According to the literary conventions of the day, the love interest is not introduced until chapter thirty, when

the pleasure balloon Bowbelle explodes, causing the first deaths since the Singularity, and Emblior is thrown into companionship with the brooding and complex Lord Zabblebrox. Love blossoms, but the disembodied head of Lord Zabblebrox’s first wife looks on disapprovingly from her Hover Jar, causing trouble between the young lovers. The novel is narrated by the twelve heads of Pastor X-12, who is relating to his cousin what he witnessed through a keyhole.

Log in with Facebook

Log in with Facebook