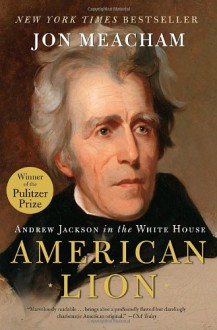

Considered by some the most dangerous man to be President and others as one of their own that deserved the office, he ushered in a sea change in Washington and American politics. Andrew Jackson: His Life and Times by H.W. Brands follows the future President of the United States from his birth in the South Carolina backcountry to frontier town of Nashville to the battlefields of the Old Southwest then finally to the White House and how he gave his name to an era of American history.

Brands begins with a Jackson family history first from Scotland to Ulster then to the Piedmont region of the Carolina where his aunts and uncles had pioneered before his own parents immigrated. Fatherless from birth, Jackson’s childhood was intertwined with issues between the American colonies and Britain then eventually the Revolutionary War that the 13-year old Jackson participated in as a militia scout and guerilla fighter before his capture and illness while a POW. After the death of the rest of his family at the end of the war through illness, a young Jackson eventually went into law becoming one of the few “backcountry” lawyers in western North Carolina—including Tennessee which was claimed by North Carolina—before moving to Nashville and eventually becoming one of the founders of the state of Tennessee and become one of it’s most important military and political figures especially with his marriage to Rachel Donelson. Eventually Jackson’s status as the major general of the Tennessee militia led him to first fight the Creek War—part of the overall War of 1812—then after the successful conclusion of the campaign was made a major general of the regular army in charge of the defending New Orleans from British attack which ultimately culminated in the famous 1815 battle that occurred after the signing of the peace treaty in Ghent. As “the” military hero of the war, Jackson’s political capital grew throughout the Monroe administration even with his controversial invasion of Florida against the Seminole. After becoming the first U.S. Governor of Florida, Jackson left the army and eventually saw his prospects rise for the Presidency to succeed Monroe leading to the four-way Presidential contest of 1824 which saw Jackson win both the popular vote and plurality of electoral college votes but lose in the House to John Quincy Adams. The campaign for 1828 began almost immediately and by the time of the vote the result wasn’t in doubt. Jackson’s time in the White House was focused on the Peggy Eaton affair, the battle over Bank of the United States, the Nullification Crisis with South Carolina, Indian relations, and finally what was happening in Texas. After his time in office, Jackson struggled keeping his estate out of debt and kept up with the events of around the country until his death.

In addition to focusing on Jackson’s life, Brands make sure to give background to the events that he would eventually be crucial part of. Throughout the book Brands keeps three issues prominent: Unionism, slavery, and Indian relations that dominated Jackson’s life and/or political thoughts. While Brands hits hard Jackson’s belief in the Union and is nuanced when it comes with slavery, the relations with Indians is well done in some areas and fails in some (most notably the “Trail of Tears”). This is not a biography focused primarily on Jackson’s time in the White House and thus Brands only focused on the big issues that is primarily focused on schools instead of an intense dive into his eight years.

Andrew Jackson: His Life and Times is a informative look into the life of the seventh President of the United States and what was happening in the United States throughout his nearly eight decades of life. H.W. Brands’ writing style is given to very easy reading and his research provides very good information for both general and history specific readers, though he does hedge in some areas. Overall a very good biography.

The presidential election of 1840 in America was a notable one for a number of reasons. Not the least of these was its result, as it was the first election in which the nominee of the Whig Party, William Henry Harrison, triumphed by defeating his Democratic opponent, incumbent president Martin Van Buren. Though this was the product of a variety of factors, foremost among them was the Whig's perfection of electioneering techniques that had emerged over the previous sixteen years, the employment of which served in many ways as a model for presidential campaigns down to the present day. In this book Mark Cheathem describes the evolution of presidential campaigning during the antebellum era, showing how these techniques emerged and how they framed the contests for the growing number of Americans voting in national elections.

As Cheathem explains, the development of presidential campaigning was a relatively recent phenomenon. With George Washington as a consensus choice, the nascent political parties did not even confront the problem of electing candidates until the third election in 1796. Even then, elections took place in a very different context, with the electoral college delegates chosen by their state's legislatures rather than in a popular vote. This changed in the 1820s as popular democracy was expanded, a development intertwined with the emergence of the "second party system" in the aftermath of the presidential election of 1824.

With the new parties now needing to appeal to this growing pool of voters they began to develop a range of electioneering devices. Here Cheathem details the emergence of a variety of tools in print, music, and visual culture that sought to promote a chosen candidate and undermine their opponent. As the dominant mass media of their time newspapers were at the forefront of this, often serving as the most direct means for candidates to reach out to their supporters across long distances. But the songs and displays at rallies also emerged as important implements for campaigns to rally voters to support their man. Cheathem also details the growing role women played in this process, as the contemporary views about their role as moral guardians proved a valuable asset in political campaigns.

Cheathem describes this in a brisk narrative that demonstrates a command of both the campaign material of the era and the secondary source literature on his subject. By weaving into this a succinct narrative of the presidential politics of the time, he provide a useful background to the issues touched upon in the campaign materials he describes. All of this is presented in a fluid text that provides its readers with a clear presentation of the era and makes a convincing argument about the development of presidential campaigning in the era. The result is a book that everybody interested in American politics should read, both for the understanding it provides in the development of modern electioneering, both for better and for worse.

The presidential election of 1828 stands as one of the most important in American history, not just, or even primarily, because of the election of Andrew Jackson that year, but because, as Donald Cole argues in this book, it marked the beginnings of the party system in American politics. While on the surface a contest between Jackson and the incumbent, John Quincy Adams, this was only the culmination of years of political maneuvering and organizing by a host of talented politicians and newspaper publishers. Cole’s book details the course of this development, looking at how the two sides struggled at both the national and local level to build a party organization that would ensure their candidate’s victory.

Cole’s begins his examination with the aftermath of the last presidential election, one of the most bitter and contentious in American history. Much of the controversy over Adams’s election reflected the changes the nation was undergoing, as a “rising tide of democracy” was broadening the electorate and challenging the domination of political offices by the elite. Because of this, the quest for the presidency became a contest over who could mobilize this growing population of voters. To that end, both sides worked to create organizations at the national, state, and local level that could advocate their cause and turn out their supporters. Here Jackson’s camp had the advantage; though their leading members were people from lower down the social scale than their counterparts, they were hungrier for office and better able to connect with the enlarged electorate. Yet for all of their handicaps Adams’s main backers, ably organized by Henry Clay and others, were no less determined to hold onto office, and Cole demonstrates that the election ultimately proved much closer than the tally indicates.

A longtime historian of the antebellum period, Cole has written a perceptive account of presidential politics in the 1820s. While never losing sight of the main protagonists, he convincingly demonstrates the decisive role that organizing at the local level played in determining the outcome. He is careful never to overstate the impact of the election, noting that the formal establishment of the political parties of the period came later, yet he make a strong case for the role of the election in enhancing democracy in the nation through the emergence of organized political camps. This combination of balance and insight make this book an excellent study not just of the presidential election of 1828, but of the emergence of the modern political process, one that can be read profitably by anyone seeking to understand party politics in our nation today.

That the race for the White House in a large republic should have been affected by the sexual history of the wife of the secretary of war seems bizarre; yet politics is often driven not only by large ideas about policy and destiny but by affections and animosities. From Helen of Troy to Henry VII, what Alexander Pope called "trivial Things" in The Rape of the Lock have led to wars, revolutions, and reformations, and so it was to be in the administration of the seventh of the United States.

As someone who hates making generalizations based off of gender:

It's so easy to tell when a historian is a man.

EDIT: To make my reasoning a bit more clear:

1) Mostly thinks of fictional examples of sex scandals involving women in power.

2) Finds the idea of sex scandals in of themselves "bizarre," despite this sort of thing affecting every woman ever in power ever.

3) Presents sex scandals (and, in the rest of the book, important women in general) in a "how did this affect the men" narrative.