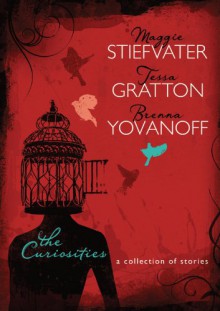

Maggie Stiefvater, Tessa Gratton, and Brenna Yovanoff are YA fantasy authors who have been writing buddies since 2008. In 2012, they decided to demonstrate what it is that their critique group does by publishing The Curiosities, a collection of short pieces that one of them had written and the other two had marked up. Now, with The Anatomy of Curiosity, they again open up their writing process, in the form of a round robin where each in turn comments on all the things that go into a work from first inklings to final revision, and each contributes a novella annotated by the author.

This is not so much “how to write” (though tips can be gathered from it) as “how I write” × 3. Stiefvater says, of how they came to work together, “their reading and writing tastes are similar enough to mine that they enjoy my writing for what it is”; yet placing their reflections next to each other makes clear that they actually work quite differently. It should encourage a beginning writer to find what suits them personally. Yovanoff has a method that everyone including her originally thought was cockeyed: she writes according to a rhythm, leaving blanks for words and paragraphs to be filled in later. And yes, her story flows rhythmically!

In her introduction to her story “Ladylike” Stiefvater describes starting it by thinking of a character interaction, then fleshing out the characters involved and expanding from there. The main character, Petra, is a painfully awkward girl who only loses her self-consciousness when reciting poetry; hired to visit and read to an elderly woman, the elegant and gracious Geraldine, Petra finds someone to admire and be encouraged by, and begins remaking herself into a better version from the seed of confidence she already had. The plot takes a dark turn when we learn that Geraldine has formerly remade herself more radically. A third character is introduced whose development complements the other two thematically. It’s a nice story, well-paced (except, perhaps, some of the large amount of quoting and discussing poetry). I found Geraldine more compelling than Petra, but maybe a teen would disagree.

Gratton’s story “Desert Canticle” takes place in a secondary world; she started with a couple of small worldbuilding details, imagined what sort of cultures might go with them, and brought those cultures to life with her characters. Her very interesting notes point out the ways in which, in the final version, worldbuilding, characters, and themes are inextricably intertwined; she also convincingly shows how she used small details to tie in themes. The story’s main character, Rafel, is a soldier who was once a very effecive killer and now has been assigned to a squad disarming magical mines, working closely with a mage, Aniv, from the people whose insurgency he helped defeat. The two of them fall in love, but over the course of the story it becomes clear how each of them has been shaped (and fettered, particularly in Rafel’s case) by their respective cultures; they may not find a way to join together. The very non-real-world cultures are excellently developed, with interesting gender dynamics (central to the story, but not the only theme); the characters are memorable and the plot is suspenseful. Recommended.

The third story, “Drowning Variations” by Brenna Yovanoff, is different because she decided to describe her writing process in the fictional form itself. The main character is an author (a version of Yovanoff) who has had two formative experiences, once when she nearly drowned as a young chld, and once when a fellow teenager drowned near her house; over the course of many years these experiences work in her head and she tries to write them over and over. We are given three very different stories (with some elements carried over from one to the next), ony the last of which she considers successful. In it, drowning, and the mental forces that sink troubled teens, are embodied as a monstrous green-haired girl. The main character, Jane, is struggling to find what to say to Ethan, the boy she’s attracted to; more so when Ethan’s best friend drowns, possibly suicide, and Ethan is visibly foundering himself. I wasn’t altogether enthused by this story, whose high-school romance seems just a bit generic and whose monster lacks consistency in description. However, the larger story’s depiction of reworking and reunderstanding a thematic idea is interesting.

The hardcover book is beautifully and legibly laid out. Overall, this is a very appealing publication.

Incredible. Normally, I can't stand short stories and flash fiction. I hate being ripped out of a world or away from characters too soon, hate the dangling, interpretative open endings, hate the overly refined clever little twists and touches.

Incredible. Normally, I can't stand short stories and flash fiction. I hate being ripped out of a world or away from characters too soon, hate the dangling, interpretative open endings, hate the overly refined clever little twists and touches.

Log in with Facebook

Log in with Facebook