It's not that often that a book about murder makes me smile, but Emsley has bit of a "Battle of the Grand Dames of Mystery" going on here. (I have put the titles in spoiler tags in case the plot description provides spoilers...)

In the red corner, Dame Agatha:

Agatha Christie built one of her murder mysteries around thallium poisoning. In

(spoiler show)1952 she wrote The Pale Horse

, in which the murderer used it to dispose of people’s unwanted relatives and disguised his activities as black magic curses. The plot involves a murdered priest and a pub owned by three modern-day witches.* Christie described the symptoms of thallium poisoning very well: lethargy, tingling, numbness of the hands and feet, blackouts, slurred speech, insomnia, and general debility, and she is sometimes blamed for bringing this poison to the attention of would-be poisoners. However, her book was responsible for saving the life of one young girl as we shall see.

In the blue corner, we have Ngaio Marsh also using Thallium:

In

(spoiler show)Final Curtain, written in 1947

, the novelist Ngaio Marsh had her villain using it. The murder to be investigated was the death of

(spoiler show)Sir Henry Ancred

who had been poisoned with thallium acetate which had been prescribed in the treatment of his granddaughter’s ringworm. Marsh clearly had no knowledge of how thallium worked in that she imagined that those poisoned with it would drop dead in minutes. Would-be murderers seeking to emulate her villain would have been very puzzled when their intended victims appeared to suffer no ill effects, although this disappointment might only have lasted a few days, and then they would have been fascinated at the many symptoms it produced.

I haven't read Marsh, yet, (something I intend to remedy someday) but one of the fun aspects in Dame Agatha's work is that she seldom gets the use of poisons wrong. Her training as a nurse and familiarity with pharmacy had much use, of course, but she also didn't slack on her research in that field.

This is the only instance in Emsley's book that cites crime writing. The rest of the book recounts real events and people.

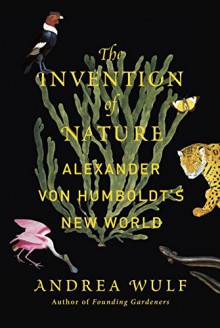

The Invention of Nature is not flawless (for me the weakest chapter was on Humboldt and Thoreau - but I've always thought Thoreau was over-rated), but it is a fascinating read.

Because before Carl Sagan's Cosmos, there was Alexander von Humboldt's Kosmos. (I don't think this is accidental, somehow.) Humboldt's was even more popular in the 19th century than Sagan's was in the 20th. Humboldt, in fact, was probably the most famous scientist of his own time - the Einstein of the 19th century. There was mass mourning when he died at 87, and mass celebrations, across the planet, on the centenary of his birth (September 14, 1869).

And today he is mostly forgotten, except in South America. Though people may wonder why there's a Humboldt Park in Chicago, a Humboldt County in California, and a Humboldt Current in the Pacific, and why many species are Humboldtii. Who was this Humboldt person, anyway?

He was the Energizer Bunny of naturalists. He never shut up, and most people didn't try to stop the font of knowledge (to quote his great friend, Goethe). Should they try, if they succeeded for more than a sentence or two, it was a miracle. He also refused to be stopped by piranhas, crocodiles, erupting volcanoes, great heights (though the very top of Chimborazo finally beat him), outbreaks of anthrax, or anything else.

He made two great expeditions - to South America, in his early thirties, and to Siberia, when he was sixty. (He longed for the Himalayas, but the British East India Company refused him permission to go.) He spent all his inherited money on science, and was forced to become a royal chamberlain at the Prussian court, waiting attendance on his king, while he longed for the Himalayas, or, at the very least, Paris. At night he wrote book after book, for some fifty years. And he found many readers.

A handful of chapters are about not Humboldt himself, but some of the men he inspired. Simon "Iron Ass" Bolivar. Charles Darwin. Henry David Thoreau. George Perkins Marsh. Ernst Haeckel. John Muir. These chapters are of varying quality, but they show that we have to thank Humboldt, at least in part, for everything from the theory of evolution to Art Nouveau to the Sierra Club.