(French text, maps and images below. / Texte français, cartes et images en bas.)

Well, consider me well and truly hooked at this point. There are a few mighty convenient and improbable conincidences --

e.g., the "inner voice" that guides Nicolas to more or less effortlessly draw pretty much the entire plot out of a wily old madam, and ink-stained footprints showing the path that a ransacking intruder has taken through Descart's home

-- surely you could have done better than that M. Parot? (I also could seriously have done without Nicolas's -- and the author's -- patronizing attitude towards Awa and her "decapitated rooster" fortune telling stunt. And towards Catherine on that same occasion, for that matter.) But at least we didn't also get the "[shocking things happening to the hero during a] dark and stormy night" cliché on the one occasion when the temptation to use it must have been huge, and I confess that both the action and the wealth of historical detail have rather drawn me in. And it certainly helps to now also know why de Sartine felt he had to select an investigator from outside the ranks of the established police force (even if neither that nor Nicolas's quick understanding and intelligence completely accounts for quite such a young, inexperience choice). By and large, though, I am really enjoying this book, and I am looking forward every day to the time I've set aside at night (and / or in the morning) for this buddy read.

That being said, even before reaching the book's halfway point -- what with the things that Nicolas had learned at the Dauphin couronné and from Antoinette, and the subsequent discoveries at Vaugirard -- it seemed to me that the mystery was pretty much solved,

and the only things remaining to be discovered at that point were the hiding place of the stolen papers, the exact role of Semacgus (if any), and the location of the final body to be found (which I'm sure we know at this point, too, even if Nicolas hasn't clued into it yet),

and I think so even more now that I'm slightly past the halfway point. Can it really take another 150+ pages to unveil the rest of what we've yet to learn? The Golden Age mystery writers published entire novels of not much more than that length ...

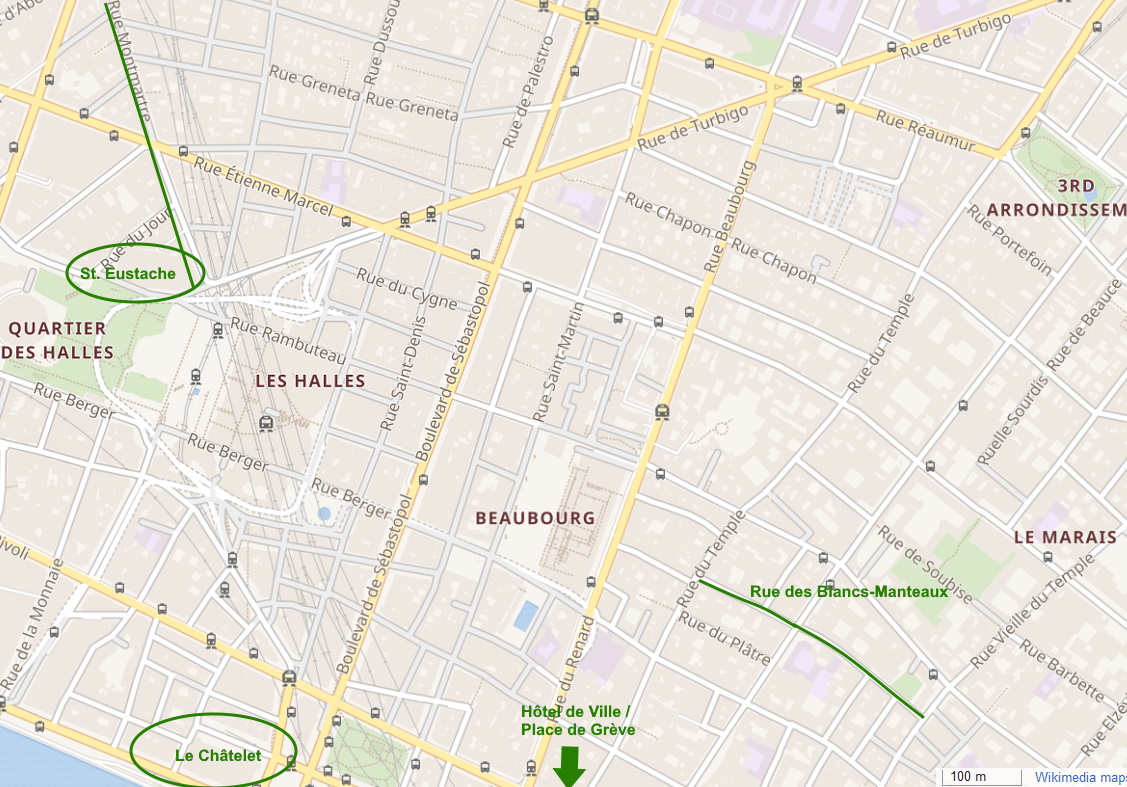

Final side note for now: I've learned a new verb -- "bastiller" (or "embastiller"). I was aware of the Bastille, of course, whose name, however, my mom's battered Petit Larousse informs me, derives from the erstwhile "bastir" ("bâtir" in modern French) -- so the name actually just denotes that it's a building -- whereas from the context it's clear that "(em)bastiller" means "to imprison". So the Bastille, much more than even Le Châtelet and the Conciergerie, was synonymous with "prison", to the point that it, in turn, gave rise to the use of a corresponding verb. Which then again, of course, only goes to underline why it played such a symbolic role in the French Revolution ...

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Eh bien, on peut me considérér entièrement captivée de l'action du livre à ce moment. Il y eu quelques coïncidences assez bien convenientes et improbables,

telles que la "voix intérieure" qui guidait Nicolas à tirer, sans effort, plus ou moins le complot entier d'une rusée propriétaire de maison infâme, et les empreintes encrées signalant le chemin pris par un pilleur pénétré à la maison de Descart

-- sûrement, vous auriez sait faire mieux que ça, M. Parot? (J'aurais bien voulu renoncer aussi à l'attitude paternalisante de Nicolas -- et de l'auteur -- vis-à-vis Awa et son coup de prophésie au coq décapité. Et, en ailleurs, vis-à-vis Catherine à la même occasion.) Mais du moins on nous épargne le cliché "[des chocs souffert par le héros durant une] nuit sinistre et orageuse" au moment où la tentation de l'user doit avoir été la pire, et il me faut admettre que l'action autant que la richesse du détail historique m'ont bien sucée dans le livre. Et bien sûr ce procès a été facilité aussi par le fait que maintenant nous savons pourquoi de Sartine le pensait indispensable de choisir un investigateur du dehors la police établie (même si ni ceci ni la compréhension rapide et l'intelligence de Nicolas expliquent entierement le choix d'un homme tellement jeune et inexpériencé). Tout-en-un, pourtant, le livre me fait grand plaisir, et je me réjouie chaque jour au temps que j'ai réservé pour ce buddy read à la nuit (et / ou au matin).

Tout ceci étant dit, même avant d'avoir achevé la moitié du livre -- en vue de ce que Nicolas avait appris au Dauphin couronné et d'Antoinette, et ses découvertes suivantes à Vaugirard -- il me paraissait que le mystère était plus ou moins résolu,

et les seules choses à découvrir ètaient la cachette des papiers volés, le rôle exacte de Semacgus (s'il en avait un), et l'endroit du corps final à trouver (lequel je suis sûre nous connaissans déjà aussi à ce moment, bien que Nicolas ne l'ait pas encore entendu),

et je pense le même d'autant plus maintenant que j'aie lu un peu plus qu'à demi du livre. Est-ce que ça prendra vraiment encore une 150e de pages de nous réveiller ce qui nous reste à découvrir? Les auteurs des romans policiers de l'Âge Doré ont publié des romans entiers de pas trop plus que ce calibre ...

Commentaire marginal final pour le moment: J'ai appris un verbe nouveau -- "bastiller" (ou "embastiller"). Je connaissais La Bastille, naturellement, le nom de laquelle pourtant, le Petit Larousse battu de ma mère m'enseigne, descend de l'ancien "bastir" ("bâtir" en français moderne) -- donc son nom seulement dénote, en effet, qu'il s'agit d'un bâtiment -- pendant que du contexte c'est clair que "(em)bastiller" signifie "emprisonner". Donc c'étail La Bastille, beaucoup plus que même Le Châtelet et la Conciergerie, qui était synonyme de "prison", au point d'engendre, en revanche, un verbe correspondant. Tout ce qui, bien sûr, de son tour seulement va à souligner son rôle symbolique dans la Révolution française ...

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

One of Parot's historical notes contains a "by the way" reminder that Nicolas's boss, Antoine de Sartine, was a historical person; he really was the Paris Chief of Police (and, for all practical purposes, the city's true administrator) during the time in which this book is set. He was reputed as a scrupulously fair and forward-thinking magistrate and a proponent of law and order, who however also didn't shy away from locking people up or taking other measures on the basis of "lettres de cachet" (unappealable extraordinary orders signed by the King or by himself), and who used a wide network of spies, both abroad and at home. His reputation preceded him to such an extent that his help and advice was frequently also sought by foreign governments and police forces. (According to Wikipedia, "once, a minister of Maria Theresa wrote to Sartine asking him to arrest a famous Austrian thief who was thought to be hiding in Paris. Sartine replied to the minister that the thief was actually in Vienna, and gave the minister the street address where the thief was hiding, as well as a description of the thief's disguise.")

At about the halfway point of our novel, Nicolas overhears a conversation between de Sartine and another official (whose identity remains undisclosed), which -- while chiefly about the disastrous French losses during the Seven Years' War and the role of Mme. de Pompadour -- also foreshadows de Sartine's later role as Secretary of State for the Navy and architect of the new French naval forces which, in decades to come, would prove such a formidable adversary to those of Great Britain.

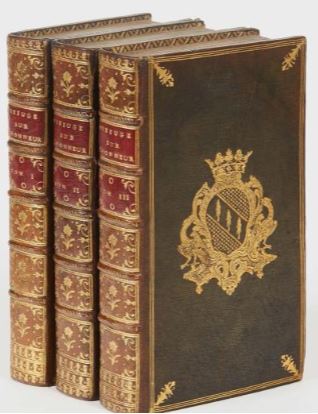

The set of books above right shows de Sartine's coat of arms, with the representation of three sardines in the center (phonetically representing his name).

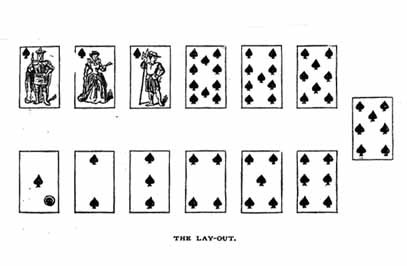

Pharaon (Faro) -- the popular card game mentioned repeatedly in the novel, especially in connection with the goings-on at the Dauphin couronné. (Another repeatedly-mentioned game is Lansquenet.)

Nicolas would probably not recognize the Faubourg Saint-Honoré of today (the location of the Dauphin couronné in the novel) -- it, and especially the rue du Faubourg Honoré, is one of the most exclusive addresses of Paris nowadays, where haute couture, art galleries, embassies, and even the entrance of the Palais de l'Élysee are all sitting right next to each other. -- (For reference, on the map the "P" of "Paris" again represents the Place de l'Hôtel de Ville / formerly Place de Grève; Le Châtelet would have been just beyond the second bridge to the left of there.)

Église Saint-Eustache -- now and then, one of the unmissable sights in the Quartier des Halles -- and its location with reference to the novel's other key locations in the centre of Paris.

For those who are already at this point in the novel: the rue Montmartre is just north of the église Saint-Eustache and the Quartier des Halles.

Log in with Facebook

Log in with Facebook

Tower of London: The round building center/left is the Bloody Tower, where King Edward IV's sons, today known simply as "the Princes in the Tower," are believed to have been held.

Tower of London: The round building center/left is the Bloody Tower, where King Edward IV's sons, today known simply as "the Princes in the Tower," are believed to have been held.