TITLE: The Invention of Nature: Alexander von Humboldt's New World

AUTHOR: Andrea Wulf

Publisher: Knopf

Format: e-book

ISBN-13: 978-0-385-35067-9

BOOK REVIEW

The Invention of Nature by Andrea Wulf is not a complete or in-depth biography, but rather a journey to discover the forgotten life (and far reaching influence) of Alexander von Humboldt, the visionary Prussian naturalist and explorer whose ideas changed the way we perceive the natural world, and in the process created modern environmentalism.

In this book, Wulf traces the threads that connect us to this extraordinary man, showing how Humboldt influenced many of the greatest artists, thinkers and scientists of his day. However, today he is almost forgotten outside academia (due to politics and changing fashions), despite his ideas still shaping out thinking. Ecologists, environmentalists and nature writers rely on Humboldt's vision, although most do so unknowingly. It is the author's stated objective to "rediscover Humboldt, and to restore him to his rightful place in the pantheon of nature and science" and to "understand why we think as we do today about the natural world". In my opinion, Andrea Wulf successfully shows the many fundamental ways in which Humboldt created our understanding of the natural world, and she champions a renewed interest in this vital and lost player in environmental history and science.

Alexander von Humboldt was one of the founders of modern biology and ecology, and had a direct effect on scientists and political leaders. Wulf examines how Humboldt’s writings inspired other naturalists, politicians and poets such as Charles Darwin, Wordsworth, Simón Bolívar, Thomas Jefferson, Goethe, John Muir and Thoreau. The author successfully integrates Humboldt's life and activities into the political and social scene so we can get a picture of how important Humboldt was, and still is. Many people considered him the most famous scientist of his age.

Humboldt was a hands-on scientist. His expeditions of discovery led him through Europe, Latin America and eventually Siberia. He strongly desired to see the Himalaya, but the East India Company didn't want to co-operate for fear that he would write unflattering comments about their form of governance.

Humboldt also continued to assist young scientists, artists and explorers throughout his life, often helping them financially despite his own debt.

Alexander von Humboldt led a colourful and adventurous life, but this book also shows us why Humboldt is so important:

- he is the founding father of environmentalists, ecologists and nature writers.

- he made science accessible and popular - everybody learned from him.

- he believed that education was the foundation of a free and happy society.

- his interdisciplinary approach to science and nature is more relevant than ever as scientists are trying to understand man's effect on the world.

- his beliefs in the free exchange of information, in uniting scientists and in fostering communication across disciplines, are the pillars of science today.

- his concept of nature as one of global patterns underpins our thinking today.

- his insights that social, economic and political issues are closely connected to environmental problems remain topical today.

- he wrote about the abolition of slavery and the disastrous consequences of reckless colonialism.

- he believed that knowledge had to be shared, exchanged and made available to everbody.

- he invented isotherms (the lines of temperature and pressure on weather maps).

- he discovered the magnetic equator.

- he developed the idea of vegetation and climate zones.

- his quantitative work on botanical geography laid the foundation for the field of biogeography.

- he was one of the first people to propose that South America and Africa were once joined.

- he was the first person to describe the phenomenon and cause of human-induced climate change, based on observations made during his travels.

- he contributed to geology through his study of mountains and volcanoes.

- he was a significant contributor to cartography by creating maps of little-explored regions.

- his advocacy of long-term systematic geophysical measurement laid the foundation for modern geomagnetic and meteorological monitoring.

- he revolutionized the way we see the natural world.

- he developed the web of life (the concept of nature as a chain of causes and effects).

- he was the first scientist to talk about human-induced environmental degradation.

- he was the first to explain the fundamental functions of the forest for the ecosystem and climate: the tree's ability to store water and to enrich the atmosphere with moisture, their protection of the soil, and their cooling effect.

- he warned that the agricultural techniques of his day could have devastating consequences.

- he discovered the idea of a keystone species (a species that is essential for an ecosystem to function) almost 200 years before the concept was named.

- he confirmed that the Casiquiare was a natural waterway between the Orinoco and the Rio Negro, which is a tributary of the Amazon, and made a detailed map.

- he considered the replacement of food crops with cash crops to be a recipe for dependency and injustice. He felt that monoculture and cash crops did not create a happy society, and that subsistence farming, based on edible crops and variety, was a better alternative.

I found the chapters that describe Humboldt's expeditions to be fascinating - filled with hazards, wild animals, pests, injuries, epidemics, new discoveries and ideas. The chapters that discuss his busy social and work life were also interesting. However, I wish the author had spend more page space on his expeditions and discoveries, and less on the biographies of the people he influenced, especially the last few chapters which were somewhat long-winded. What I found rather refreshing was the lack of author speculation and interjection of her own theories - the narrative sticks to what is known. The author also manages to convey Humboldt's enthusiasm and energy so that the reader feels breathless just reading about all his activities.

This biographical search for the invention of nature and the man who "invented" it, provides a great deal of food for thought, woven around the life of a great (and overly energetic) scientist. This was an enjoyable and informative reading experience.

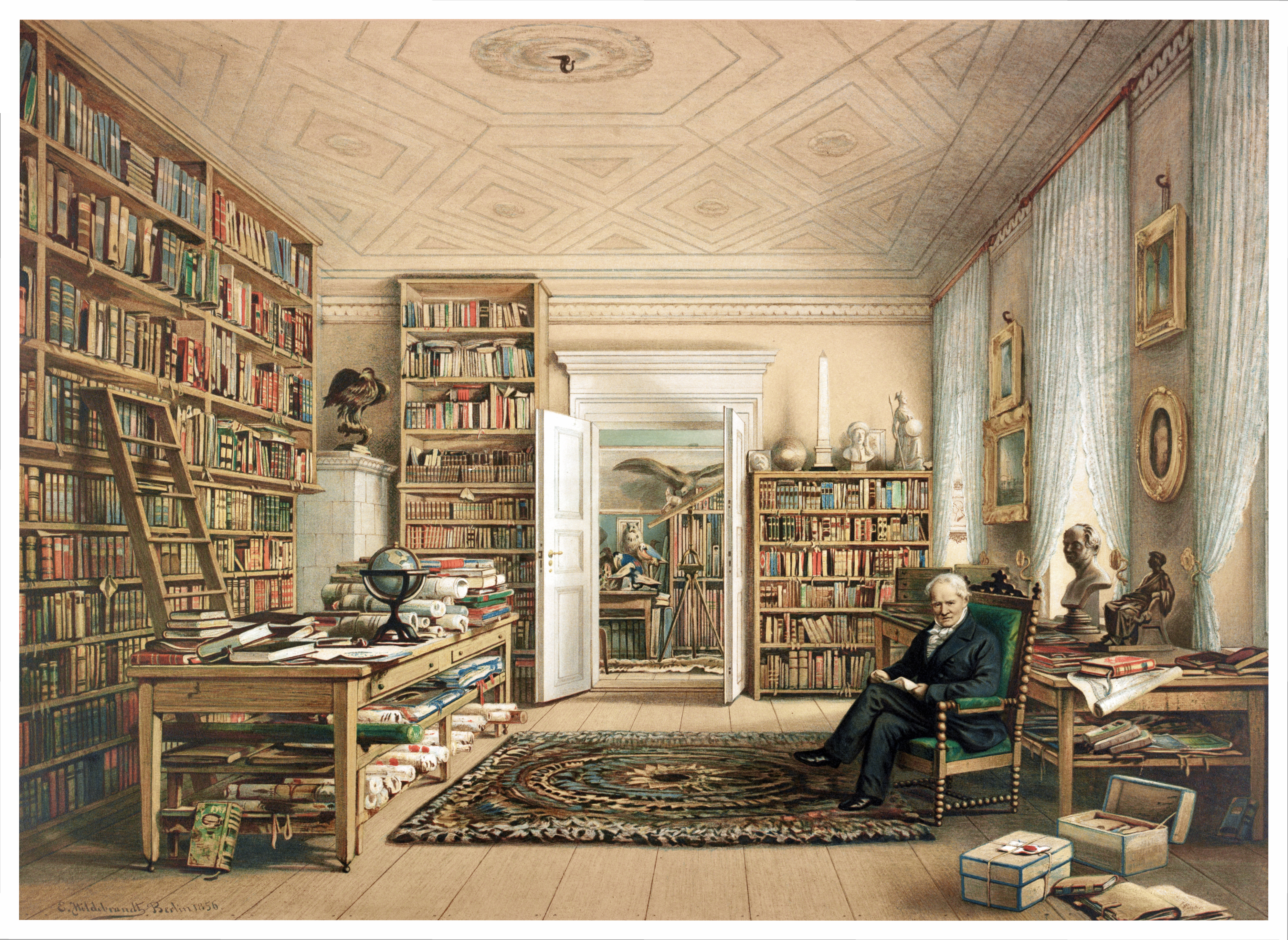

NOTE: This book includes three clear, easy to read maps that were particularly useful in following Humboldt's Journeys, and a large number of black and white, as well as colour illustrations were also included in the book. In addition, the author included an extensive section of notes, sources and bibliography, an index and a note on Humboldt's publications.

Log in with Facebook

Log in with Facebook