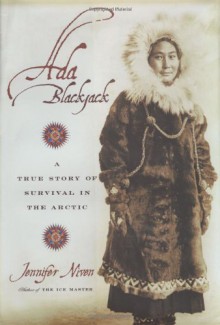

I had not heard of Ada Blackjack before seeing this book. The story sounded interesting, and since it was on sale, I figured why not.

Blackjack was only of five people (and the only woman as well as the only Inuit) to go to Wrangel Island, a decision that seems to be an ill conceived attempt to prove a silly point as well as to gain a useless island from Russia.

Gain for the Canadians that is.

This book will make you want to find Dr Who, steal the Tardis, go back in time, and hit people upside the head.

While Blackjack was Inuit (Eskimo), she was raised in the city so the survival skills that many of people learned, she didn’t have. Her first husband was abusive, and her first son ill. She took a job as a seamstress to the men going to Wrangel Island. Once there, far from home, things went bad quickly.

It is to Niven’s credit that she doesn’t whitewash anything, though she presents it with a degree of understanding. While the men’s treatment of Blackjack at some points is reprehensible, Niven points out why the men might have saw it as necessary, even as she points out while Blackjack acted the way she did. The treatment of Blackjack after her rescue is less understandable. The best parts of the book are those chronicling Blackjack’s struggle to survive on the island, in particular her discovery of her strength.

The book does confront, though doesn’t entirely answer, questions about men and women were viewed, and the white man’s view of the Inuit, in particular of Inuit women.

Disclaimer: Arc via Netgalley.

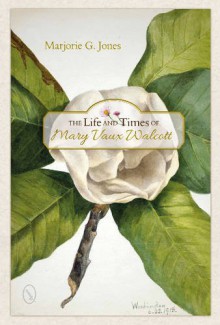

While I live in the same city which Walcott spent much of her life and have been to the Smithsonian many times, I can honestly say that the name did not register with me. I can say that after reading the book, I must have seen some of her paintings of plants (she was call the Audubon of Botany), but it never stuck.

Shame really.

Walcott was a Quaker who married for the first time in her fifties, angering her father who saw her as his permanent nurse.

That’s not the most fascinating thing about her however.

Jones’ book is a short biography, more like an introduction to Walcott. Yet, there is much here that will make any reader want to investigate further, not just about Walcott but about the other women who she sometimes met, and whom her father blamed for her betrayal. It is almost as if these women, who explored the environment are their own club. It’s quite interesting.

Perhaps the iffiest part of the book is the section concerning Walcott’s view on Native Americans. She was appointed a commissioner for the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Walcott’s view on Native Americans, while sympathetic, was more in keeping with her times and is, at the very least, disturbing and disappointing to read today. It is true Jones’ credit that she doesn’t try to whitewash this and even compares Walcott’s reaction to that of Estelle Brown, whose views are more in keeping with today. She also examines why the views were different and why Walcott would not have supported someone such as Lydia Maria Child.

ARC via Netgalley.

I really couldn’t care less about American football. Truly, couldn’t care less. Yet, I felt it was necessary to read this book because even I am aware of the various stances sport writers have taken over the name of Washington, DC’s football team. It’s like the only time I have like Bob Costas (I have never forgiven him for describing a cantering horse as flying like Pegasus).

King’s book focuses on the debate about the name of Washington’s team. For the record, in case you don’t know, the football team in Washington DC is called Redskins. This is a derogatory term for many Native Americans, and, according to King, it is basically the equivalent of the n word..

And really, you don’t even need to know the second part. It should be enough to know that it is an insult.

There has been an increasing vocal protest movement against racially incentive names for sports teams in the United States. Washington’s team is only the most obvious case in point. King’s book traces not only the meaning of the name, but also the various arguments presented by the name’s defenders and those who argue for the name’s removal.

King’s discussion of the terms history also includes how the term and where it is used can affect people. The name isn’t the sole issue, though it is a large part of it, but also is the use of the name while on land that was gained as the result war and/or resettlement as well as the taking of Native American children and forcing them into government Christian schools.

It is to King’s credit that he also looks at the motivations of those who want the name to stay. He does focus on the question of emotional ties to the name. While King clearly ranks these emotional attachments as less importance (and rightly so in my mind), he at least explores the ideas and the reasons for it. He also, then, quite deftly dismantles the arguments put forward by the team as well as the “we have Native Americans that like the name point”.

Quite frankly, you will most likely not want to root for Washington in any sporting event.

You also might find your view of such teams, like the Braves, changing as well.

At times, the book does get a little repetitive, and sometimes, I found myself wishing that at one point there was clear definition of difference and honoring. Is any Native American reference in a sports team an insult? I’m not asking to be smart nor do I mean to suggest that dressing up as a Hollywood Indian to support a team is not insulting; I seriously want to know. For instance, is there any way that the Washington (or any sports team for that matter) is legitimately honoring a Native American tribe and/or group? Is even asking the question insulting? In fairness to King, most likely this question has been addressed in his other books.

Another weak point is the section about the use of the term Redskin by non NFL sport teams. This chapter could have been more detailed, including the look of the term as used by high schools. This is made up by the section discussing the difference in view of those Native Americans who live on reservations versus those who either do not live or have lived away from reservations for a long period of time.

Seriously, this book should be required reading for any American sports fan.

This is one of those books where you understand why it won a prize.

Odds are you've heard of the Mandan people, even if you are not aware of them. Lewis and Clark met them; it's where Sacajawea and her husband joined the group.

Wein's book is a, as she calls it, a mosaic. It is not a linear history, but more of a cultural history. It's fascinating and the parts about the Native Americans and disease are particularly hard to read. The book is not only about the interactions between various Native American groups but also about first encounters. If you have read the works of Mann, check this out.