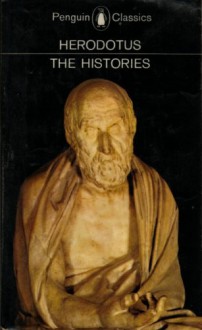

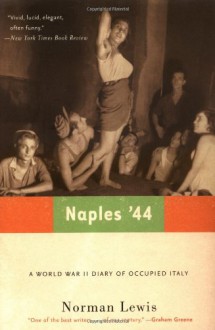

Located in the Ancient Agora in Athens, under the reconstructed Stoa (porch) of Herod Atticus, is a bust of what could be considered to be the world's first ever historian.

It always fascinates me that in an era long before photography was ever conceived, and the ability to paint was restricted to basic drawings and sketches (if indeed they have survived), that because of the skill and ability of the ancient sculptors we are able to have a good idea of what these ancient people looked like. As for me, when I wondered into the Stoa of Atticus on hot Greek summer sunday, I stood amazed before the bust of Herodotus and said to myself, 'so, he did have a beard'.

Anyway, for those who have been dying to know where Frank Miller got the idea for these movies (and comic books from which the movies were adapted):

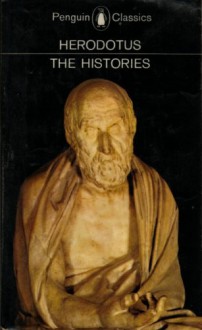

then this is the book. In fact, Herodotus of Halicarnasus, in the opening paragraph, says that the purpose of this book is for the readers to understand the background to how these particular events occurred, namely the war between the Persians and the Greeks, which culminated in the battles of Thermopylae (300), Salamis (300: Rise of an Empire, though the movie is much, much, much more loosely based on the actual events than is 300) and Plataea (mentioned in passing at the end of 300). Oh, and I probably should also mention the battle of Marathon, where the Athenians managed to defeat the Persian landing party using the same tactics that Hannibal used to defeat the Romans at Cannae.

Herodotus brings back a lot of memories for me though, especially sitting in Ancient Greek translating the entirety of book (or chapter) two, which is an 80 page exposition on the Egyptian culture (which, in my own opinion, is quite fascinating, particularly since he notices that the Egyptians practiced circumcision). Anyway, there have been a number of debates as to whether Herodotus is actually a history, or whether it is more of an anthropological text because he does spend an incredible amount of time exploring the culture and practices of many of the nations that live in the regions that he is interested in (namely everything to the east of Greece because, for some reason, in Herodotus' world, there is nothing all that much interesting to the west, despite the fact that at this time Rome did exist as a city – though he does mention Carthage and the Greek colonies in Sicily).

They (and by they I pretty much mean everybody) refer to Herodotus as the 'Father of History' and in many ways that is the case. The original Greek title of the book is 'Historia' which, in Greek, means, well, a story or a tale, which is in many cases correct because it is the story, or the tale, of how we arrived at this particular point. Ignoring all of the distractions (and there are some pretty fascinating distractions at that) regarding the cultural behaviours of the people that Herodotus explores (for instance the Persians did not have market places, the Egyptians loved al-fresco dining, and the Scythians did not believe in marriage, but rather shared and shared alike), the whole purpose of this incredibly long (and fascinating) book is about the Third (or second, depending on whether you include the first attempted invasion of Greece where Darius' fleet was destroyed off the coast of Mount Athos) Persian War and the victory of the Greeks over the much more powerful Persian Empire (though one could say that this is not actually all that surprising considering that at the time the Persian Empire had reached the limits of its power).

Another thing they (and by that I mean a handful of Classical Historians) say about Herodotus is that he is the 'Father of Lies'. Personally I thought that this is probably a little bit too harsh for the poor guy since the Bible refers to this guy:

as the father of lies, and I won't throw in the picture of some politician as another comparison since, as everybody knows, all politicians lie for their own benefit. Anyway, back to Herodotus and as to why they refer to him as such. First of all it seems that it is because he writes about a number of things that he himself could simply not know about. This I feel may be a little strenuous because throughout his book Herodotus does indicate that he obtained much of his information from people who have been to those places or where witnesses to those events, and we also need to consider that back in those days the writers (especially the first Historian) did not need to quote sources in the same way that academics do today. The other reason that I suspect is probably because Herodotus is writing from an Hellenic point of view meaning that one could consider that much of his writings are little more than propaganda, exulting the Greeks above that of the other races. However the fact that Herodotus goes into enormous details in relation to the other cultures that existed around him at the time, I believe, is evidence against the idea that Herodotus is little more than an Ancient Greek propagandist.

The final thing that I want to look at is Herodotus' relationship with the Bible. Okay, as far as I know nobody is using Herodotus as a means to disprove the accounts of the Old Testament because, well, he is neither here nor there with regards to the accounts in the Bible. For those who want to disprove the Bible, my position is that you are going to have to look elsewhere because the fact that Herodotus does not mention the Jewish nation is a pretty flimsy attack, especially since at the time of Herodotus' writing it was most likely around the time the Jews had returned from exile and were probably did not even appear on his radar. In fact, you will notice that Herodotus does not even mention the existence of the Philistines or any of the other tribes that inhabited the area (though we should note that when the Assyrians and Babylonians conquered Palestine they shifted the populations around so as to prevent nationalist uprisings).

What we do have with regards to Herodotus and the Bible (with the exception of the three main kings of Persia, who are mentioned in both accounts) is the fall of Babylon. For those who believe that there is a difference (Herodotus mentions two incidents, though the second was a nationalist uprising against the Persian overlords) we need to consider the reasoning behind the two accounts. Herodotus is writing a detailed history of the Greco-Persian conflicts and in doing so is writing a history of the Persian Empire from its inception. One of the significant events in the rise of the Persian Empire was the fact that they managed to conquer the Babylonian Empire (who had previously held sway over the Middle East), and Herodotus goes into explicit details in how that happened. The Biblical account of the fall of the Babylonian Empire can be found in the book of Daniel (Chapter 5). Here we have what is in effect a very brief description of what happened, namely Belshazzar went to sleep (probably quite drunk) King of Babylon and work up a Persian slave. The reason that Daniel does not go into explicit detail in relation to the fall of Babylon is that he is not writing a history but rather a theological tract and in doing so he is demonstrating the power of God over the Earthly authorities. Up until that time nobody imagined that Babylon would fall. Even though at the time the Persian army was camped outside the gates of the city, nobody believed that they would be able to breach the walls. However, the Persians did manage to breach the walls and the Babylonian empire was overthrown. Daniel's purpose was not to say how it happened (most likely because his readers probably already knew how it happened) but rather he was showing God's hand in the event. What Herodotus shows us, though, is how it happened, and by reading Daniel's account we can see God's hand in these events.

For those who are interested, I have written a blog post on what the world would have been like if the Greeks had lost at Marathon, and lost at Salamis.

Log in with Facebook

Log in with Facebook

The best part of this book is where us readers get a glimpse at the times when Kapuściński is setting out on his fledgling career

The best part of this book is where us readers get a glimpse at the times when Kapuściński is setting out on his fledgling career  Herodotus’s opus appeared in the bookstores in 1955. Two years had passed since Stalin’s death. The atmosphere became more relaxed, people breathed more freely. Ilya Ehrenburg’s novel 'The Thaw' had just appeared, its title lending itself to the new epoch just beginning. Literature seemed to be everything then. People looked to it for the strength to live, for guidance, for revelation.

Herodotus’s opus appeared in the bookstores in 1955. Two years had passed since Stalin’s death. The atmosphere became more relaxed, people breathed more freely. Ilya Ehrenburg’s novel 'The Thaw' had just appeared, its title lending itself to the new epoch just beginning. Literature seemed to be everything then. People looked to it for the strength to live, for guidance, for revelation. Here he is, in his yellow shirt!

Here he is, in his yellow shirt!

At Sealdah train station, Culcutta, Kapuściński encounters poverty and distress that beggars belief:

At Sealdah train station, Culcutta, Kapuściński encounters poverty and distress that beggars belief:

Hyderabad

Hyderabad