This is a version of some comments I made on a fascinating post about this novel that Debbie Reese put up on her blog American Indians in Children's Literature.

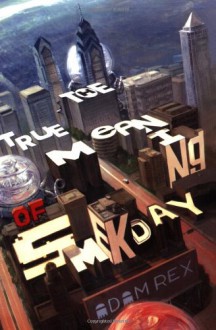

The True Meaning of Smekday tells about eleven-year-old Gratuity's experiences as two different groups of aliens invade the earth. Rex does some very clever things here in terms of paralleling the alien invasions with what happened between imperialist invaders and Indigenous people in North America and elsewhere. I think, though, that Rex's main interest throughout appears to be in exploring the humor of the situation, and while that means there’s often clever and funny satire that emerges from the colonialist parallels, that doesn’t happen consistently. Sometimes the novel is a colonial satire, and sometimes it isn’t.

For instance, it seems that the appearance and character of the alien Gorg has satiric implications: they have the uniformity, the self-centered self-importance, and the obsessive single-mindedness of totalitarian overlords, like Hitler or the British raj or the European settlers of North America. But there is no satiric implication that I can find in the fact that the other aliens, the Boov, have a sizeable number of feet. It’s just a joke, just something that defines them as alien.

Similarly, I think, what happens sometimes resonates in terms of the history of relationships between Indigenous North Americans and European colonists and sometimes it doesn’t. And sometimes, much worse, it resonates in what I see as negative ways that I suspect Rex wasn’t even aware of.

I think that happens, for instance, with the portrayal of Chief Shouting Bear, whose shouting about Native rights turns out to be a role he adopts to keep people from getting too close to him and his secrets. I like how the Chief slyly manipulates stereotypes of angrily politicized Native Americans in order to keep people from interfering in his life. He creates a safe space for himself by pretending to be something that confirms other people's negative stereotypes and makes those other people want to avoid him. But while the distance between the stereotype and the real, clever, kind man who hides behind it seems to imply the falsity of the stereotype, it also in an odd way also confirms the stereotype: the novel never suggests that there aren’t a lot of angry Native Americans who shout too loudly about their land and their rights, etc. Nor does it suggest that the anger is justified and even necessary, or that is anything but just silly and laughable. Indeed, the novel seems to be sending up the supposed silliness of politicized Native people who want to make others aware of their rights at the same time as it seems to be expressing concern about how powerful outsiders oppress people and deprive them if their rights. The novel is just too interested in making jokes and being funny to be consistent enough to be effective as satire. As a result, it undermines its own satire.

My main concern with the novel, though, is that while it makes significant points about how colonizers oppress others, points that seem modeled on the history of European settlers and Indigenous North Americans, it finally seems to want to dismiss the significance of that history and invite readers of all sorts to believe that the past is the past, what’s over is over, and that since we’re really all alike we should be forgetting our differences (and apparently the history behind those differences) and just treat each other as equals and get along. Gratuity, the protagonist who is telling what happened, implies that sort of tolerance message when she says, “The Boov weren’t anything special. They were just people. They were too smart and too stupid to be anythng else.” And the Chief agrees: “When you’re Indian, you have people telling you your whole life ‘bout the people who took your land. Can’t hate all of ‘em, or you'll spend your whole life shouting at everyone.”

The novel also undermines its colonialist satire by identifying a number of other forms of oppressions of weaker people by more powerful ones: women by men, children by adults, etc. Even Gratuity herself has to acknowledge at one point that maybe she’s too bossy and should stop oppressing others. As a result, the specific history and issues of Native Americans become just one example of a more general attack on mean bullies who take advantage of weaker people; and the solution to that particular situation as well as all other situations and relationships is just being nice to others and treating them all as equals.

To me, that reads like a massive copout, a way of avoiding the important political and historical issues that still control and limit far too many lives. And like, for instance, a lot of multicultural rhetoric, it works to erase the ongoing significance of the specific history of Indigenous peoples—what makes their situation different from those of all the other groups who now live together in countries like the US.

One final point: for someone who spends a lot of time attacking and making fun of imperialists blind to the equal humanity of people they see as different and inferior to themselves, Rex himself, quite unconsciously, I suspect, makes a hugely imperialistic mistake. He asserts that the Boov force all the inhabitants of Earth to move to Florida, and then, changing their minds, to Arizona. But he then says nothing about how the Earthlings from, say, Europe or Africa, are going to manage to get to Florida. And when Gratuity arrives in Arizona, there is no mention of people who speak Swahili or Chinese, no mention of there being disputes involving people from different countries or continents, no mention of orders given in any languages other than English and Spanish. In fact, Rex has simply assumed that the Earth = the USA. All the humans who are not American are simply erased. It’s only in one sentence towards the end that Rex hints that maybe the Boov had rounded up other people in other parts of the world in different detention areas closer to where they live--a weird thing to suddenly tell readers about when we’ve been asked all along to assume that all humanity had ended up in Arizona. This is unconscious American imperialism at its finest, and as a Canadian, I found it exceedingly annoying.

All things considered: I think that The True Meaning of Smekday is often a very funny novel, and often a cleverly satiric one. But while it certainly has the potential to give readers of all ages a lot to think about, I find myself saddened by the ways in which it sets up parallels that allow for shrewd commentary on American Indian history and politics and then squanders the opportunity to pursue that commentary in favor of jokes and a kind of obvious and dangerous message of thoughtless universal equivalence and tolerance.

Log in with Facebook

Log in with Facebook