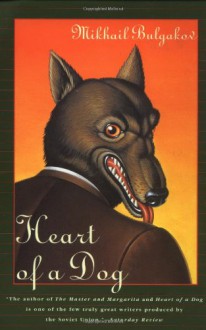

"The whole horror of the situation is that he now has a human heart, not a dog's heart. And about the rottenest heart in all creation!"

The recipe for success a la Bulgakov:

# Take a street dog, hungry and flea-ridden and wickedly smart (yes, he can even read - you gotta do that to survive on the cruel winter Moscow streets!).

# Take a brilliant and renown professor with a knack for brain surgery/transplants and desire to advance science.

# Add to the mix a dead good-for-nothing delinquent alcoholic's brain.

# Add the flavor of the Soviet mid-1920s, after the Socialist Revolution but still before the iron fist rule of Stalin's terror policy.

# Let Bulgakov's genius mix all of these ingredients together - and you will end up with a brilliantly written satirical fantastical commentary-on-contemporary-society laughter-through-tears piece of literary art that is Heart of the Dog.

Despite its short size, this book has endless layers. On the surface, it is a hilariously sad story about a science experiment gone very wrong in the direction that its creator did not quite anticipate, and all the funny antics of the newly created sorta-human Sharikov. Yes, that includes obsessive and funny cat-chasing even when the dog becomes "human". On the other level, it is a cautionary warning about what happens when power falls in the hands of those who should not be allowed to yield it, and the dangers and pitfalls of the system that allows that to happen. Yes, that includes an easy step from killing cats to pointing guns at real people, and demanding sex in exchange for keeping a job, and of course the ultimate evil that was to penetrate the fabric of the years to come - writing denunciations for little else than petty personal gains.

"But just think, Philip Philipovich, what he may turn into if that character Shvonder keeps on at him! I'm only just beginning to realize what Sharikov may become, by God!"

"Aha, so you realize now, do you? Well I realized it ten days after the operation. My only comfort is that Shvonder is the biggest fool of all. He doesn't realize that Sharikov is much more of a threat to him than he is to me. At the moment he's doing all he can to turn Sharikov against me, not realizing that if someone in their turn sets Sharikov against Shvonder himself, there'll soon be nothing left of Shvonder but the bones and the beak."

I do believe that this book should be used as an illustration of the whole "laughing through tears" concept. It's the epitome of that concept. At times sidesplittingly funny with some sad overtones, it quickly crosses the territory into the mostly sad and even scary, especially given the context of the events still to come to this world of Soviet Union in the mid-1920s. Yes, it's the Stalin era and the Purges and the labor camps and denunciations and mass trials of the "enemies of the people" that I'm talking about. For the characters of this book, these events are just a few years away.

Keeping this in mind, you quickly realize that Bulgakov's short novel has undoubtedly way more impact on its reader now than it did back in the mid-twenties when it was written. Back then it was sad and funny, and held a note of warning, and shed the uncomfortable light on the parts of the pre-Stalinist pre-Purges society that were already beginning to feel uncomfortable. However, it ended on a quasi-happy note, the futility of which had only become fully visible years later. And now, for the readers that have the benefit of knowing what history had in store just a few short years later for the likes of those "undesirable elements" described in this book, the impossibility of anything remotely good coming out of the whole situation and of the entire future for Bulgakov's characters becomes painfully clear.

'But Philipp Philippovich, you're a celebrity, a figure of world-wide importance, and just because of some, forgive the expression, son of a bitch… Surely they can't touch you!'

'All the same, I refuse to do it,' said Philipp Philippovich thoughtfully. He stopped and stared at the glass-fronted cabinet.

'But why?''Because you are not a figure of world importance.'

'But what…'

'Come now, you don't think I could let you take the rap while I shelter behind my world-wide reputation, do you? Really… I'm a Moscow University graduate, not a Sharikov.'

C'mon, we all know that even world-class fame will never save Professor Preobrazhenky from Stalin's labor camps as eventually his higher-up protectors will themselves become victims of the new regime, and likely from a gunshot to the head in the middle of the night. And Bormental's fate will undoubtedly be very similar to that - just as Professor kinda-sorta anticipated already. After all, neither of them has made their unpopular views very secret.

"'Yes, I don't like proletariat,' sadly agreed Philipp Philippovich."

And Professor Preobrazhenky's clearly anti-socialist views definitely would not make his ultimate fate anticipated by the reader after the events of this story any easier. His grumpy views of a cultured and educated person who is baffled and annoyed with the "new" society of coarseness and rudeness and inefficiency and "class struggle" and the undeserved in his opinion entitleness of those who perceive themselves as the oppressed working class and whom Professor in turn perceives as lazy and irresponsible people. And among the rambles of the old and annoyed man there may or may not be a grain of truth. Judge for yourself:

'What do you mean by "ruin"? Is it an old woman with a stick? A witch who smashed all the windows and put out all the lights? There's no such thing! What do you mean by that word?' Philipp Philippovich angrily inquired of an unfortunate cardboard duck hanging upside down by the sideboard, then answered the question himself. 'I'll tell you what it is: If instead of operating every evening I were to start a glee club in my apartment, that would mean that I was on the road to "ruin". If when I go to the lavatory I don't piss, if you'll excuse the expression, into the bowl but on to the floor instead and if Zina and Darya Petrovna were to do the same thing, the lavatory would be ruined. Ruin, therefore, is not caused by lavatories but it's something that starts in people's heads. So when these clowns start shouting “Stop the ruin!” – I laugh!'

But there is much more to this book than just the condemnation of the system. Had it been only that, it would have become quite dated quite soon. No, just like in Bulgakov's other works, it has a commentary on the state of humanity as a whole, on what makes us truly human versus merely humanoid. It is about the importance of morals and values, the etiquette and politeness and respect that make us really human, and moreso, civilized humans.

'I'm sorry, professor, not a dog. This happened when he was a man. That's the trouble.'

'Because he talked?' asked Philipp Philippovich. 'That doesn't mean he was a man.'

And this respect for culture and etiquette and civility is what permeates the message of this book. This respect for what Bulgakov sees as the essentials of being human are precisely what puts him in the conflict with his contemporary Soviet state that believed in intimidation and terror as the viable way of governing and existing - the principles that newly formed humanoid Sharikov is very eager to learn and internalize. And neither Bulgakov nor Professor Preobrazhensky or Bormental are having that.

"Kindness. The only possible method when dealing with a living creature. You'll get nowhere with an animal if you use terror, no matter what its level of development may be. That I have maintained, do maintain and always will maintain. People who think you can use terror are quite wrong. No, no, terror is useless, whatever its colour – white, red or even brown! Terror completely paralyses the nervous system."

"Nobody should be whipped. Remember that, once and for all. Neither man nor animal can be influenced by anything but suggestion."

Well, my review is getting long and I have nothing bu praise for this book. So I will wrap up with the highest possible recommendation for any fans of Bulgakov or, really, any fans of well-written literature.

5 stars.

Log in with Facebook

Log in with Facebook