There are melodies so unique that it’s enough to hear their first notes to know what is coming. Without doubt the Boléro by Maurice Ravel (1875-1937) is such a memorable piece of music. Although it’s a classical orchestra tune and not actually new – it premiered as a ballet in November 1928 –, virtually everybody knows it at least partly; most people will even remember the name of its French composer notwithstanding that they may never have heard any other work of his. After all, Ravel was celebrated already during his lifetime and his fame hasn’t faded since his tragic death following the desperate attempt to stop or even reverse his mental decline with brain surgery. But what kind of a man was Maurice Ravel apart from his compositions? In his short critically acclaimed biographical novel Ravel, which first appeared early in 2006, the French author Jean Echenoz evokes the last decade in the life of the musical genius starting with his 1928 grand tour of America.

Actually, Jean Echenoz set his unusual as well as comical opening scene of Ravel in the world-famous composer’s house in Montfort-l’Amaury that inspired him to write this almost completely fact-based biography in the first place. More precisely he shows the celebrated star in his bathtub on the morning of his departure for the USA on one of the last days of 1927 musing whether he should venture out of the warm water. It quickly becomes clear that Ravel is a bachelor who attaches such great importance to his appearance that it’s almost an obsession… and that it’s difficult for him to ever get ready on time. Moreover, his behaviour marks him as eccentric and inconsiderate. On this particular morning, for instance, he leaves his friend Hélène Jourdan-Morhange waiting for him outside in her cold car for almost an hour and it doesn’t once occur to him that he could invite her in to warm up. When he finally emerges from the house, he is neat like a pin, the spit image of a – rather short and slightly old-fashioned – dandy in his early fifties on his way to the racecourse. Hélène takes him to Paris to make sure that the always-confused musical genius catches the special train to Le Havre where the steamer SS France is waiting to take him along with about two thousand others to New York. He is tired and grumpy because as so often insomnia has plagued him during the night, but he hopes that the six-week passage will be as good as a holiday for his strained nerves. Unfortunately, people recognise him, ask him for autographs or to play something. And insomnia doesn’t spare him, either. In New York begins an exhausting four-month concert tour crisscross America that Jean Echenoz skilfully traces without deviating unnecessarily from known facts. By the middle of the novel it’s late in April 1928 and the composer returns to France and his life continues as ever. He travels, attends concerts and mundane parties, smokes without end, but most importantly he writes the Boléro and the Piano Concerto for the Left Hand in D Major. All the while, Ravel struggles with insomnia, boredom and indolence as the author shows at length and with the sly wit characteristic of him. After a car accident in October 1937, however, the humorous tone of the novel changes from major to minor key. Although the composer isn’t very seriously hurt, it’s from this moment that his mind increasingly fails him until he no longer knows how to write or to read and he not even recognises his own music. Doctors recommend a craniotomy as last treatment option. Ten days later the musical genius is gone.

Having read only a German edition of Ravel, it would be preposterous of me to comment on Jean Echenoz’s language and style although I think that unusually much of the original wit shines through in the translation by Hinrich Schmidt-Henkel at my hand. Certainly, it’s a succeeded biography that makes skilful use of dry facts from the composer’s life setting them against the backdrop of his time to show the unique character of Maurice Ravel as his contemporaries have known and loved him. Moreover, the gifted narrator doesn’t depend on dialogue or extensive stream-of-consciousness to make the celebrated star appear as a human being with odd edges like everybody else instead of some kind of unearthly genius. It’s definitely a worthwhile read – not just for lovers of classical music.

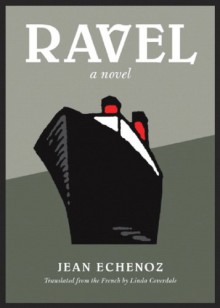

Ravel - Jean Echenoz,Linda Coverdale

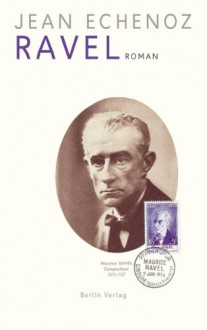

Ravel - Jean Echenoz

Ravel - Jean Echenoz

If you’d like to read a work of fiction from the pen of Jean Echenoz, I recommend his 1999 novel Je m’en vais available under the English title I’m Off, but also brought out as I’m Gone. Click here to read my review on Edith’s Miscellany.

Log in with Facebook

Log in with Facebook