I'm a little late with my reviews of the books of 1915! Then again, what's really the difference between a century, and a century and ten weeks?

The Song of The Lark by Willa Cather

I’m going to go out on a limb and say this was the best novel of 1915. When I told my brother I was reading The Song of The Lark, he said he had read it too, after he had read a mention of it in an article by Arlene Croce saying that it was one of the only novels about the development of a young girl into an artist. I was curious exactly what kind of zingy one-liner had entranced my brother into reading this book, so I looked up what Croce said specifically, and it was in a review of the dancer Suzanne Farrell’s autobiography. “Holding On to the Air isn’t really the inside story of Suzanne Farrell and George Balanchine. The real inside story would take a writer of Willa Cather’s stature to deal with. In The Song of the Lark, Cather’s novel about a girl from a prairie town who becomes a great Wagnerian soprano, we discover the true dimensions of a life lived for art.” I do wish that I got to read more often about a girl developing into a great artist. In addition, the main character was a florid example of Enneagram Type Four, my favorite type, which I just loved.

The protagonist, Thea, is a Scandinavian-American girl living in a no-account town in Colorado. She has always felt that she is different from everyone else, and is fiercely sensitive and beset by envy. She is taking piano lessons from a decrepit alcoholic who was once a brilliant pianist, and it is understood that when she is grown she can make her living as a piano teacher herself. The town doctor is her closest friend and confidant. There’s a freight train conductor, Ray, who is in love with her even though she’s only eleven. Cather manages to convey this as sort of sweet but I still couldn’t help reading it as creepy. However,

Ray dies before he can get his hands on Thea, and he leaves her some money which allows her to go to Chicago at the age of seventeen to study piano.

(spoiler show)

Always in her heart she’s thought of herself as a singer, but she’s too independent-minded and it’s too precious for her to discuss it. However, when her piano instructor finally hears her sing, he sets her on another path.

Although Thea is very single-minded about her art, she does fall in love at one point with a rich young man. Unfortunately

he’s a louse who doesn’t tell her until after he’s proposed and they’ve gone away together that he’s already married and can’t get a divorce. (His wife “goes mad” and is put in the asylum. Did she have syphilis or was that in another book of 1915?)

(spoiler show)

Willa Cather writes about this guy like she likes him, but I don’t. I do get the impression that Cather finds it hard to take romantic love between a woman and a man very seriously. Anyway, the rich beau does remain very loyal to Thea, and so does her doctor friend.

One thing that’s really notable about this book is how not-racist it is, compared to most of the books of 1915. As a girl, Thea likes to hang out with the Mexicans who live in her town, especially Spanish Johnny and the other musicians. These characters and their music are described with seriousness, individuality, and respect. (I don’t think she achieved this high standard in all her books, though. I’m not looking forward to Sapphira and the Slave Girl, Cather’s last novel, but maybe by 2040 I’ll be too old and decrepit to review books.) Anyway, Cather’s descriptions overall are marvelous. They have a poignant quality, making me feel as if she’s depicting my own self, when nothing could be farther from the truth.

What I remember best about this book is a long conversation my wife and I had about the following passage about childhood and having a rich inner life:

“But you see, when I set out from Moonstone [her hometown] with you, I had a rich, romantic past. I had lived a long, eventful life, and an artist’s life, every hour of it. Wagner says, in his most beautiful opera, that art is only a way of remembering youth. And the older we grow the more precious it seems to us, and the more richly we can present that memory. When we’ve got it all out,—the last, the finest thrill of it, the brightest hope of it,” she lifted her hand above her head and dropped it,—“then we stop. We do nothing but repeat after that. The stream has reached the level of the source. That’s our measure.”

When I was looking for the Arlene Croce quotation online, I found a lot of other strange quotations about Willa Cather. People have many weird things to say about her. For example, in an extremely transphobic and unreadable 1997 New Yorker article, the author speculates that Willa Cather would have been “impatient” with Brandon Teena and considered his “gender confusion” as “self-indulgent.” I think of all the authors of this time period, Willa Cather would be the least likely to be a hater, but obviously no one including me has any idea what she thought (or would have thought) about something that didn’t have a name in her time period. Gore Vidal in 1992: “(Willa Cather) liked men to be men, and women to be men, too. She seemed unaware of the paradox.” Huh? It seems that Willa Cather conjures up some very strong ideas in people’s minds and she is still kind of a lightning rod when it comes to gender.

Something Fresh by PG Wodehouse

This is hands-down the funniest novel of 1915. All of Wodehouse’s novels are hilarious. Probably the reason I didn't crown this one as the best novel is a terrible societal prejudice against comedy. This one is in the Blandings Castle series, where people end up at the country home of kooky Lord Emsworth, none of them who they are pretending to be. This time, the heroes are two young struggling but spirited writers, a woman and a man, who both become enmeshed in the quest to steal back an Egyptian scarab that Lord Emsworth has absentmindedly walked off with. There are a number of delightful subplots and love plots, and several characters have health problems with the lining of their stomachs. The only thing that was at all tough about this marvelous novel is that the details of all the imposters are so intricate that when I put the book down for a week I had trouble remembering what was really going on when I picked it back up.

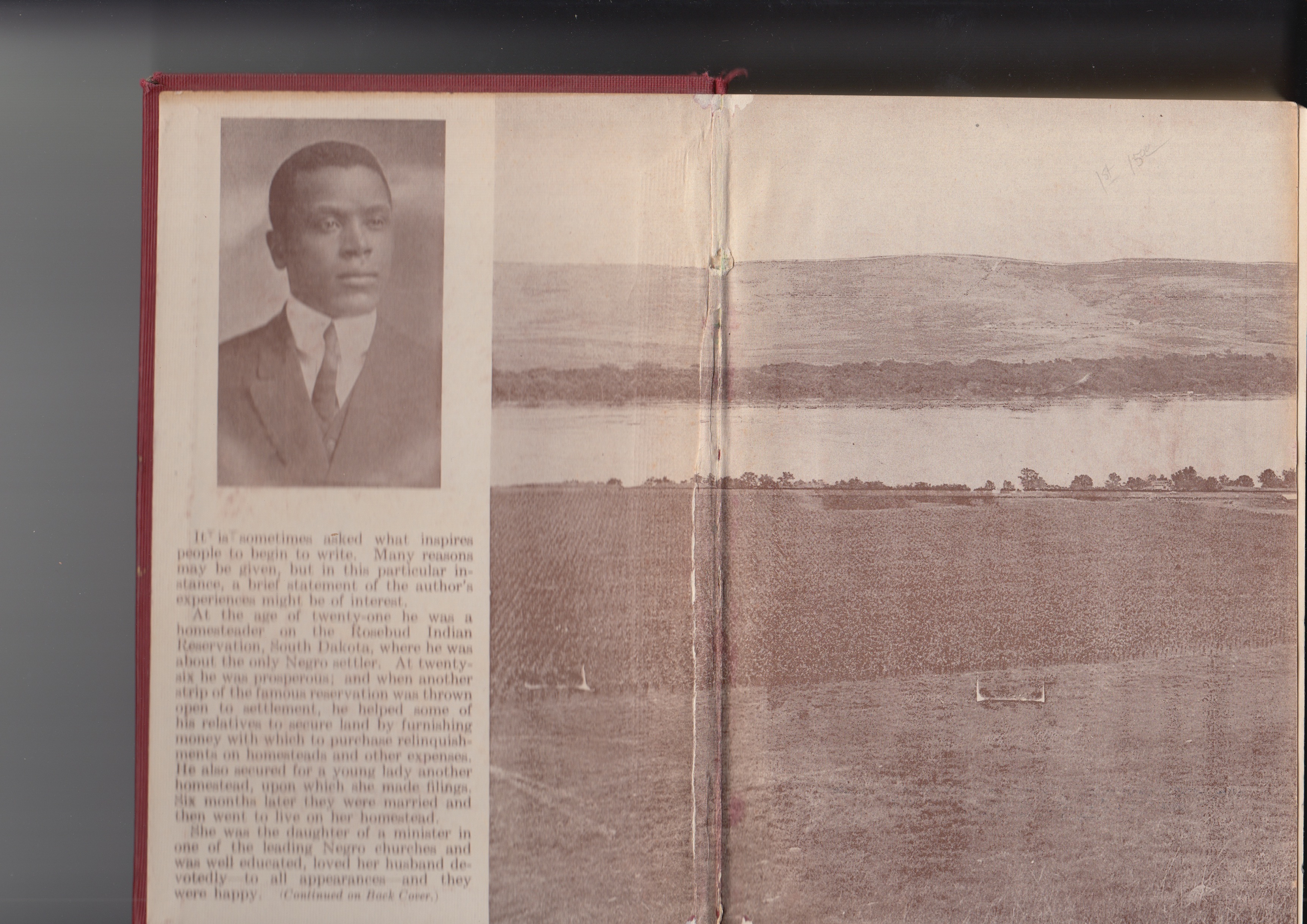

The Forged Note: A Romance of the Darker Races by Oscar Micheaux

This was one of my favorites of 1915. It was different from all the others in several ways, the most obvious and notable one being that it was written by an African-American author. So as I opened it up I was really rooting for it to be good. I was a little perturbed by the dust jacket copy, which was a perplexing diatribe describing how the author had been cheated out of his homestead by his ex-wife and ex-father-in-law, very similar to the kind of off-the-wall, off-topic back cover copy you might get on some contemporary self-published books. This contretemps with the homestead involved a forgery, so from the title it looked like this would be the plot of the book. But it became clear that the homestead-marriage-forgery had all been covered in Micheaux’s previous novel The Conquest: The Story of a Negro Pioneer (which I should have read in 2013 but didn’t because 2013 was such a hard year.) It also became clear that although the hero of The Forged Note has a different name from the hero of The Conquest, this is basically a sequel, and very closely based on Oscar Micheaux’s real life. So, for example, the hero of The Forged Note is an author whose ex-wife and her father conspired against him, and he is now engaged in selling his first novel. Confusing? Yes! Meta and interesting? Yes!

Micheaux has a very engaging style and describes things in a witty way. The main character, Sydney Wyeth, travels to different cities to sell his novel to the black community. He does very well selling it door-to-door to domestic workers and other people with humble jobs, but it angers him that the intellectual leaders like teachers rarely buy his book. He thinks they’re a bunch of hypocrites, and even worse are the pastors, who are depicted as a bunch of ignorant power-hungry men who only seek to aggrandize themselves. (Although there’s also one good pastor character to act as a foil.) Even though Sydney is very clean-living, he finds petty criminals who get drunk and gamble away all their money amusing and good company. These characters, who would be the villains or jokes of other books, are three-dimensional, realistic, charming people.

Because Sydney is so handsome, a number of women are interested in him, but he keeps thinking of a woman he knew that he had to give up because of a shocking secret he learned about her. Meanwhile, far away, too-sweet-for-this-world Mildred can’t stop thinking about Sydney, so she sets out to sell his book as well.

Sydney is a close observer of human nature, and he sees a lot of interesting things. Like so many of these old books, the things that are most fascinating to a modern reader are too ordinary for the author to even make note of. And there were a couple of places where I could not understand what was going on. Unsurprisingly Micheaux paints a grim picture of Jim Crow cities. Black people aren’t allowed to use the library, playgrounds, or community centers so there’s literally nothing for kids to do. Lynchings are mentioned casually, and the police arrest black people for being out on the street at night. This happens to Sydney, and when he goes to his court date, he is thrown back in jail for being articulate and insufficiently cringing. The lesson this character takes from this is that he should never show up at his court date and just say goodbye to his bond money. To me it seemed like a lot of this stuff is unpleasantly relevant to today.

Sydney (and Micheaux) have no interest in white racism or why it exists or whether it might be overthrown; it’s just a force of nature that’s part of the landscape. One of the other characters, a newspaper editor who like Sydney seems to be a mouthpiece for Micheaux’s views, says that white people will always hate black people and that’s just the way it is. Instead, Sydney/Micheaux was hung up on the idea, which seems completely bonkers to a modern reader ie me, that the black people weren’t working hard enough. For example, in one of the cities (I forget which one because they all had pseudonyms) there was a movement to open either a library or a YMCA for African-American people. A Jewish donor promised a sum of money but only if it were matched by an equal sum. The churches were apathetic and didn’t raise nearly enough money. Sydney is enraged by this and writes an editorial in the paper talking about how lazy and no-good the black people of this city are. He leaves town immediately because he knows everyone will be mad, and I don’t blame them. Talk about kicking people when they’re down! At this point I really lost patience with Sydney. I think he’s an Enneagram Type 1 so he has a lot of great qualities but he also has a stick up his butt and he thinks he’s always right and that everyone should be like him.

But it’s really interesting to read what is basically a civil rights story that’s actually from the time period. I feel like when I read these things framed as historical narratives, it doesn’t show the in-fighting and batshit craziness and sense of hopelessness that I get from this novel, and I know those are all characteristics of present-day activism. Also, when I was discussing this novel with my wife, but talking about it as if it were science fiction, she said that if her life were completely circumscribed by weird aliens who hated humans, she wouldn’t be mad at the aliens either, she would just be mad at her fellow humans, so maybe Micheaux’s response is more natural than I thought.

As far as the library/YMCA goes, Mildred saves the day by donating the missing amount of money, which was something like $10,000 that she made selling books. But various characters express doubt whether the library/YMCA will even make any difference or if the community will even appreciate it. Oy! By the way, everyone and everything in The Forged Note has a pseudonym. W.E.B. DuBois is called Derwin, and The Crisis is called The Climax. I forget what Booker T. Washington is called; I should have taken notes. I think Atlanta is called Attalia. Leo Frank is called “The Jew.” :( (That whole part was depressing.)

At last,

Sydney and Mildred get together, and we find out what the forged note of the title was. If I’m remembering right, Mildred’s father engaged in a forgery and got into terrible debt, which Mildred got the family out of by selling herself to a wicked man and losing her virtue. Luckily Sydney understands her true worth.

(spoiler show)

Something one of the Micheaux mouthpieces says (maybe the editor again) is that there are no black novels with a romance between two black characters, because no one can take seriously that there would be two such people of fine character and that their love would be worth writing about. Micheaux clearly set out to right a wrong, or “write” a wrong, and I think he succeeded because it is a grand romance in the melodramatic style of the time. He really was a trailblazer as well as a great writer, and I think this book was an epic accomplishment, especially when the plot makes it clear how hard it was to sell a book of this kind. This novel made me think more than any of the other books of 1915 (even if what I was thinking was sometimes, “This is completely whacko!”) Also just about everything in this novel is relevant in some way to the #WeNeedDiverseBooks conversation currently happening about the publishing industrial complex. Actually, I would make make the argument that not much has changed since 1915 in this area, except that today there is a different set of stereotypical stock characters, and it’s depressing. I don’t know how well known Micheaux was at the time but I think today he is a complete unknown; I never would have heard of him if it weren’t for this project. If Micheaux is famous at all, it’s as a film maker, but I think he deserves a big reputation as a novelist.

Pointed Roofs by Dorothy Richardson

Another top book of 1915 by an author I’d never even heard of. Dorothy Richardson is a modernist writer, and one of the first to use interior monologues or “stream of consciousness.” Pointed Roofs is about a shy, awkward English girl whose father has lost all his money, so she goes to Germany to become a teacher in a girls’ finishing school. (All this really happened to Richardson.) Of course it reminded me a little bit of Villette, and the nice part is it reminds the main character of Villette too. The novel had such a natural, authentic-feeling flow. It is so refreshing and inspiring to read the thoughts and feelings of a girl, treated with such seriousness and depth. I feel like even in contemporary literature, men’s feelings are serious business and women’s feelings are chick lit, so for Richardson to have pulled this off in 1915 fills me with profound respect and gratitude. I really liked how the main character was able to relax and play the piano better once she got to the German school; it seems like just being British is a huge handicap to emotional and artistic development. The interplay between the girls at the school seemed very realistic. Everything that happened was realistic! Because Richardson was presenting such a slice of life, there were more things that I had no idea what the hell they were than in other books of 1915, because she was talking about products and fads of the day without explaining what they were. This may mark me as an incredibly shallow person, but one of the most interesting parts was when the main character Miriam is forced to have her hair washed when “Miriam’s hair had never been washed with anything but cantharides and rose-water on a tiny special sponge.” To her horror, hair washing involves having a raw egg cracked onto her hair. In some ways 1915 is just like today; in other ways it’s like another planet. I’m pleased there are many more books to come by Richardson.

Strange Life of Ivan Osokin by P.D. Ouspensky

This was the last book of 1915 I read. I kept putting it off because I was sure it would be incredibly boring and all about philosophy. I mean, Ouspensky, right? Surprise!! This was amazing, one of the best. Guess what? It is about time travel! I used to be obsessed with time travel and have read so many time travel novels, and even written some, and even got one published. So I thought I knew all the usual time travel tropes and tricks. But Strange Life of Ivan Osokin is completely original. It’s a completely realistic novel about time travel. This is what time travel would really be like if it were possible, or maybe it even is actually happening constantly.

You know how sometimes the character travels back in time but because of the rules of time travel, or to keep from changing the future, or because of meddling by the super-villains, nothing can be changed? This book is NOT like that. In this story, nothing changes because the protagonist is too stuck in his ways to change, even though that’s the very reason why he traveled back in time to live life again as his younger self. You think you would do things differently if you were fourteen again, but would you really? Why would you, you are the same person you were before. At first I felt very sympathetic to Ivan as he makes the identical mistakes he set out to avoid. Because being in school is so horrible. It’s easy to think if you had a chance to do it all over again you’d be a success this time, but actually it’s a no-win situation and you still wouldn’t want to do your homework. And I felt sympathetic to Ivan as he decided that this time his mother wouldn’t die. It is such an awful and impossible thing to believe, that your mother will ever die, no wonder he still can’t believe it even after he’s already lived through it. Even after he’s longed so much to see his mother again, when he does get to spend time with her, he’s churlish and uncommunicative just like he was the first time around, and he still causes her trouble that (he believes) contributes to her early death.

But it’s hard to maintain sympathy with Ivan as he spirals down through his life. The magician told him he would remember that he had traveled through time as long as he wanted to remember it, and he doesn’t want to remember anymore. Then he meets Zinaida. She’s the reason he wanted to have a second chance, a chance to win her. When we met her the first time, at the very end of their relationship, she seemed sulky and spoiled and to be toying with Ivan. But once I got to see the actual arc of their relationship, everything she did and said made a lot of sense; this was very nicely laid out. I was really just at the edge of my seat waiting to see what would happen when the loop closed. And is this the second time he’s lived through his life, or maybe the third? Can he get out of the loop? Usually, I’m pretty cavalier about spoiling the books of 1915 but I think I’ll pause here, because you probably really want to go out and read this very accessible and short science fiction novel.

I said that The Forged Note was the book of 1915 that made me think the most, but actually it was this one. The Forged Note made me think in an academic way about black people of 1915, which is very nice but not super relevant to my life. This book made me think really hard about me and my life and what the hell should I do? You can’t ask for much more than that. Just in case you are too lazy to read Strange Life of Ivan Osokin, I’ll give you the fruits of my labor. Obviously, Ivan is just like me, and possibly you, so I studied his mistakes closely to see how I can avoid them. These are his problems. 1) He daydreams all the time, like me. After becoming a schoolboy again, how does he occupy his mind? By thinking about a made-up universe called Oceanis. Well, naturally. 2) He never talks to anyone about real stuff. Not once does he tell a friend, “Hey, this weird thing is happening to me. I think I traveled through time.” And he never tells Zinaida how he really feels; he just blathers on. 3) Ivan never mends fences with anyone he’s had a fight with. He just assumes they hate him forever and he writes them off. I bet an apologetic letter to his uncle would’ve gone a long way. 4) He cares what other people think about him. He gambles away his last dollar because he’s self-conscious about how he looks to a bunch of rich people. Actually, no one really cares what anyone else does and they’re all completely oblivious because they’re busy thinking about Oceanis or being caught in their loop themselves. So why bother? 5) He’s hella lazy. How about when Zinaida tries to get him a job as a civil servant and he turns it down even though he’s penniless, because he’s a poet. 6) He’s always making plans for the future, or thinking about how he did things wrong in the past. He is in the present zero percent of the time.

That’s the one that really got me, because isn’t making a catalog of your own/Ivan’s mistakes just another way to defer everything to the future or past? This one seems like the real problem, especially in a time travel scenario, which is every scenario really because in regular life you are supposedly traveling from the past into the future but all the time you are only ever in the present. Strange Life of Ivan Osokin makes it clear that everyone is going through their life as a zombie, stuck in the same patterns they’ve always been stuck in, and the only other option is to wake up. So then I got to thinking, is it really a good thing to be woke? Because if you are awake and present, that means being awake and present to a lot of extremely unpleasant experiences. Honestly there are advantages and disadvantages to being a zombie. Ultimately I decided that since being in the present is one of my wife’s very few interests I might as well be there with her since I married her and stuff.

Anyway, that’s enough about me. Another feature of Strange Life of Ivan Osokin is a recurring reference to an English fairy tale which is very haunting; I don’t know if it’s a real fairy tale or if Ouspensky made it up. And there are a few references to an upcoming revolution in Russia that are interesting. And I really like the open-ended nature of the book’s conclusion:

The Gurdjieff-type magician has warned Ivan that it’s very easy to get distracted, and you can almost see it about to happen to Ivan. Because on the one hand everything that Ivan thinks he wants is available to him, but on the other hand he knows that it won’t work out and he is doomed to make the same mistakes again unless he becomes a completely different person.

(spoiler show)

I wonder what he will do? I was really pleased to learn that Ouspensky has a non-fiction treatment of the same material, called A New Model of the Universe.

Log in with Facebook

Log in with Facebook