What with the pandemic still very much ongoing, BL acting up again, MR's and Char's resulting posts re: BookLikes, the BL experience, and moving back to Goodreads, this feels like a somewhat odd moment to post my half-yearly reading stats. I hope it won't be the last time on this site, but I fear that the community to which I've belonged for almost a decade -- longer than to any other online community -- and which, most recently, has played a pivotal role in making the Corona pandemic more bearable to me, is on the point of breaking up. And frankly, this is making me incredibly sad.

Book-wise, too, the pandemic has had a huge impact on my reading; for three out of the past six months, I pretty much exclusively withdrew into Golden Age mystery comfort reads, because I just didn't have it in me to tackle anything else. Though I suppose in comparison with others, who went into more or less full-fledged reading slumps, I can still color myself lucky.

That said, the past six months' reading highlights definitely included all of the buddy reads, both for the shared reading experience and for the books themselves -- as well as a number of books that I read either before the pandemic began or in the very recent couple of weeks ... though I'm tempted to list every single favorite Golden Age mystery that I reread during the pandemic, too; in addition to a whole number of new discoveries. So, without further ado (and roughly in reverse chronological order):

Highlights:

The Buddy Reads:

Jean-François Parot: L'énigme des blancs-manteaux (The Châtelet Apprentice)

Jean-François Parot: L'énigme des blancs-manteaux (The Châtelet Apprentice)

The first of Parot's Nicolas le Floch historical mysteries set in 18th century Paris. Nicolas is a Breton by birth and, on the recommendation of his godfather, a Breton nobleman, joins the Paris police force under the command of its (real) Lieutenant General Antoine de Sartine, one of the late 18th century's most influential statesmen and administrators. -- Parot was an expert on the period and a native Parisian, both of which elements clearly show in his writing, and I'm already looking forward to reading more books from the series.

French-language buddy read with Tannat and onnurtilraun -- we're now also looking into the possibly of "buddy-watching" the (French) TV adaptation starring Jérôme Robart.

The pandemic buddy reads; including and in particular:

* Josephine Tey: A Daughter of Time (with BT's and my individual add-on, Tey's play Dickon, written under the name Gordon Daviot, which likewise aims at setting the record straight vis-à-vis Shakespeare's Richard III) -- A Daughter of Time was a reread; Dickon was new to me.

* Georgette Heyer: No Wind of Blame (the first of the Inspector Hemingway mysteries -- also a reread);

* Agatha Christie: Towards Zero and Cat Among the Pigeons (both likewise rereads);

* Ngaio Marsh: Scales of Justice (also a reread; one of my favorite Inspector Alleyn mysteries);

* Cyril Hare: Tenant for Death (the first Inspector Mallett mystery -- new to me);

* Patricia Wentworth: The Case Is Closed (Miss Sliver book #2 -- also new to me; this isn't a series I am reading in publication order).

Dorothy Dunnett: The Game of Kings (book 1 of the Lymond Chronicles

Dorothy Dunnett: The Game of Kings (book 1 of the Lymond Chronicles

16th century Scotland; the adventures of a main character somewhere between Rob Roy, Robin Hood and Scaramouche (mostly Scaramouche), but it also features a range of strong and altogether amazing female characters. Another series I'm looking forward to continuing.

The first buddy read of the year, together with Moonlight Reader, BrokenTune, and Lillelara.

My Individual Highlights:

Bernardine Evaristo: Girl, Woman, Other

Bernardine Evaristo: Girl, Woman, Other

Heaven knows the Booker jury doesn't always get it right IMHO, but wow, this time for once they absolutely did. If you haven't already read this, run, don't walk to get it. And though initially I was going to say "especially if you're a woman (and from a minority)" -- no, I'm actually going to make that, "especially if you're a white man".

Saša Stanišić: Herkunft (Origin) and Gaël Faye: Petit pays (Small Country)

Saša Stanišić: Herkunft (Origin) and Gaël Faye: Petit pays (Small Country)

Two autobiographical books dealing with the authors' genocide experience, in Bosnia-Herzegovina and Burundi, respectively. Stanišić's account -- an odd mix of fact on fiction, which does lean pretty strongly towards the factual, however -- asks, as the title indicates, how precisely our geographical, ethnic and cultural origin / sense of "belonging" defines our identity; and it focuses chiefly on the refugee experience and the experience of creating a new place for oneself in a new (and substantially different) country and culture. Faye's short novel (barely longer than a novella) packs an equal amount of punch, but approaches the topic from the other end -- it's a coming of age tale looking at the way our cultural identity is first drummed into us ... and how ethnic stereotypes and hostilities, when fanned and exploited, will almost invariably lead to war and genocide.

Josephine Tey: The Inspector Grant series, Dickon, and Miss Pym Disposes

Having already read two books from Tey's Alan Grant series (The Daughter of Time and The Franchise Affair) as well as her nonseries novel Brat Farrar in past years, and Miss Pym Disposes at the beginning of this year, I took the combined (re)read of The Daughter of Time and the play Dickon during the pandemic buddy reads (see above) as my cue to finally also read the rest of the Inspector Grant mysteries. And I'm glad I finally did; Tey's work as a whole is a paean to her much-beloved England -- and though she was Scottish by birth, to a somewhat lesser degree also to Scotland --; a love that would eventually cause her to bequeathe her entire estate to the National Trust. -- Though the books are ostensibly mysteries, the actual "mystery" element almost takes a back seat to the land ... and to its people, or rather to people like those who formed Tey's personal circle of friends and acquaintances. And it is in creating characters that her writing shines as much as in the description of England's and Scotland's natural beauty.

Pete Brown: Shakespeare's Local

Pete Brown: Shakespeare's Local

Another book that I owned way too long before I finally got around to reading it; the discursive -- in the best sense --, rollicking tale of one London (or rather, Southwark) pub from its earliest days in the Middle Ages to the 21st century, telling the history of Southwark, London, public houses, and their patrons along the way. The title is glorious conjecture and based on little more than the fact that the pub is near the location of Shakespeare's Globe Theatre (combined with the equally demonstrable fact that Shakespeare loved a good ale and what today we'd call a pub crawl) ... so it's highly likely that, like many another celebrity over the centuries, he'd have had the occasional pint at this particular inn, the George, as well.

Dorothy L. Sayers: Love All

Dorothy L. Sayers: Love All

A delightful drawing room comedy that was, owing to its completion during WWII, only performed twice during Sayers's own lifetime and never again thereafter, which is utterly unfair to both the material and its author -- topically, this is the firmly tongue in cheek stage companion to such works as Gaudy Night and the two speeches republished under the title Are Women Human? (I'd call it feminist if Sayers hadn't hated that term, but whatever label you want to stick on it, its message comes through loud and clear and with plenty of laughs.)

Christianna Brand: Green for Danger

Christianna Brand: Green for Danger

One of the discoveries of my foray into the realm of Golden Age mysteries; an eerie, claustrophobic, psychological drama revolving around several suspicious deaths (and near-deaths) at a wartime hospital in Kent during WWII. None of Brand's other mysteries that I've read so far is quite up to this level, but she excelled in closed-circle settings featuring a small group of people who all genuinely like each other (and really are, for the most part, likeable from the reader's -- and the investigating policeman's -- perspective, too), and in this particular book, the backdrop of the added danger arising from the wartime setting adds even more to the tension. It's also fairly obvious that Brand was writing from personal experience, which greatly enhances every single aspect of the book, from the setting and the atmosphere to the individual characters.

Sonia Sotomayor: My Beloved World

Sonia Sotomayor: My Beloved World

Sotomayor's memoirs up to her first appointment to the Federal Bench. What a courageous woman! A trailblazer in every sense of the word -- a passionate advocate for women, Latinos/-as (not just Puerto Ricans), those hindered in their career path by a pre-existing medical condition (in her case: diabetes), and more generally, everybody up against unequal odds. Fiercely intelligent and never satisfied with second best (for herself and others alike), she nevertheless comes across as eminently likeable and open-minded -- on the list of people I'd like to meet one day (however unlikely), she shot right up to a top spot after I'd read this book; in close vicinity with Michelle Obama.

John Bercow: Unspeakable

John Bercow: Unspeakable

Bercow's time as Speaker of the House of Commons was doubtlessly among the more remarkable periods in the history of the British Parliament, both on account of his personality and of the momentous decisions taken during those years; and his unmistakeable style jumps out from every page of his memoir -- as well as every minute of the audio edition, which he narrates himself. The last chapter (his attempt at outlining the odds for Britain post-Brexit) was already obsolete before the Corona pandemic hit; this is even more true now. However, the vast majority of the book makes for a fascinating read, not least of course because of his insight into the politics -- and politicians -- of his time (he is neither sparing with the carrot nor with the stick, and some of his reflections, e.g., on the qualities of a "good" politician / member of parliament, would constitute ample food for thought for politicians anywhere).

Statistics:

As I said above, the one thing that definitely had the biggest impact on my reading in the first six months of 2020 was my three-month long "comfort reading" retreat into the world of Golden Age mysteries. So guess what:

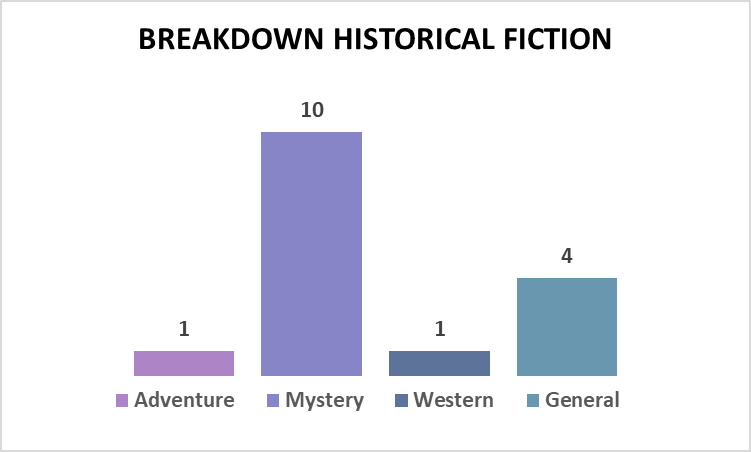

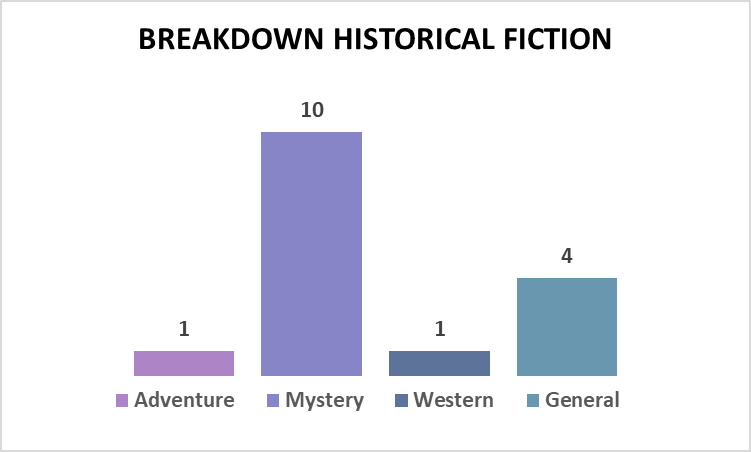

Of the 129 books I read in the first six months of 2020, a whopping 63% were Golden Age and contemporary mysteries -- add in the 10 historical mysteries that also form the single biggest chunk of my historical fiction reading, you even get to 91 books or 70.5%.

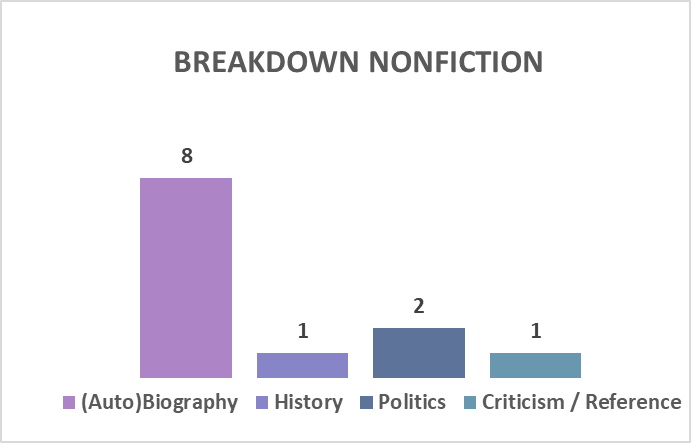

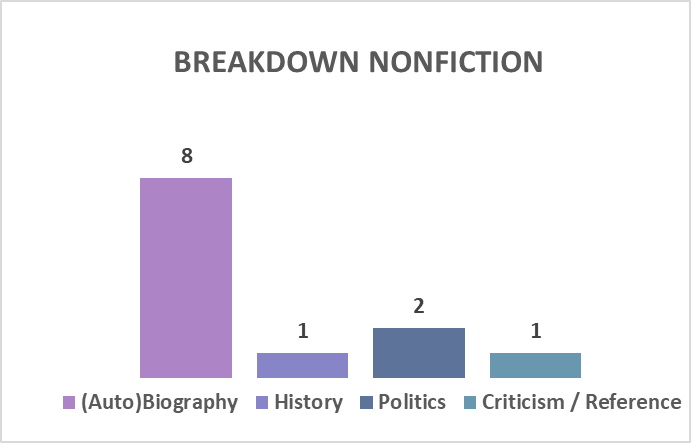

I am rather pleased, though, that -- comfort and escape reading aside and largely thanks to a number of truly interesting memoirs and biographies -- the number of nonfiction books is roughly equivalent to the sum of "high brow" fiction (classics and litfic).

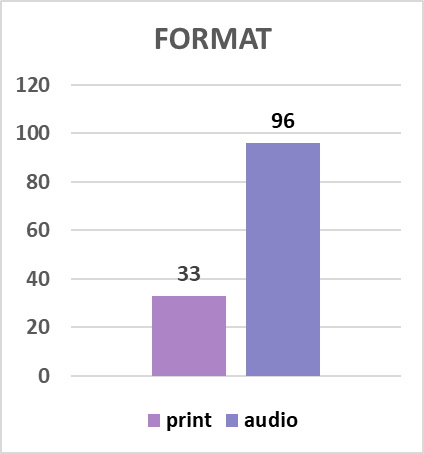

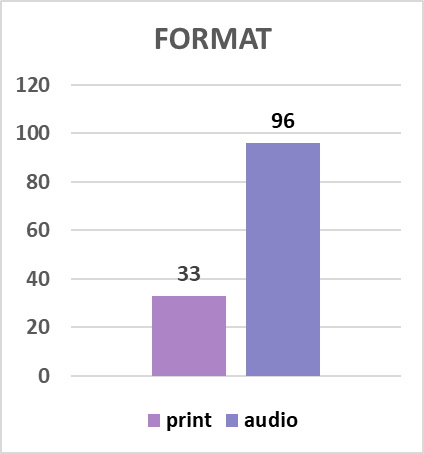

Another thing that makes me happy is that my extended foray into Golden Age mysteries was not overwhelmingly limited to rereads; these accounted for only 28% of all books read (36 in absolute figures), a percentage which is not substantially higher than my average in the last two years. At the same time, as a comparatively large number of Golden Age mysteries are not (yet?) available as audiobooks -- not even all of those that have been republished in print in recent years --, and as I have spent considerably less time driving to and from meetings and conferences than in the past two years, the share of print books consumed is higher than it was in 2018 and 2019.

Given the high percentage of comfort reading, it's no surprise that my star ratings are on the high side for the first half of 2020 -- the vast majority of the books were decent, if not good or even great reads.

Overall average: 3.7 stars

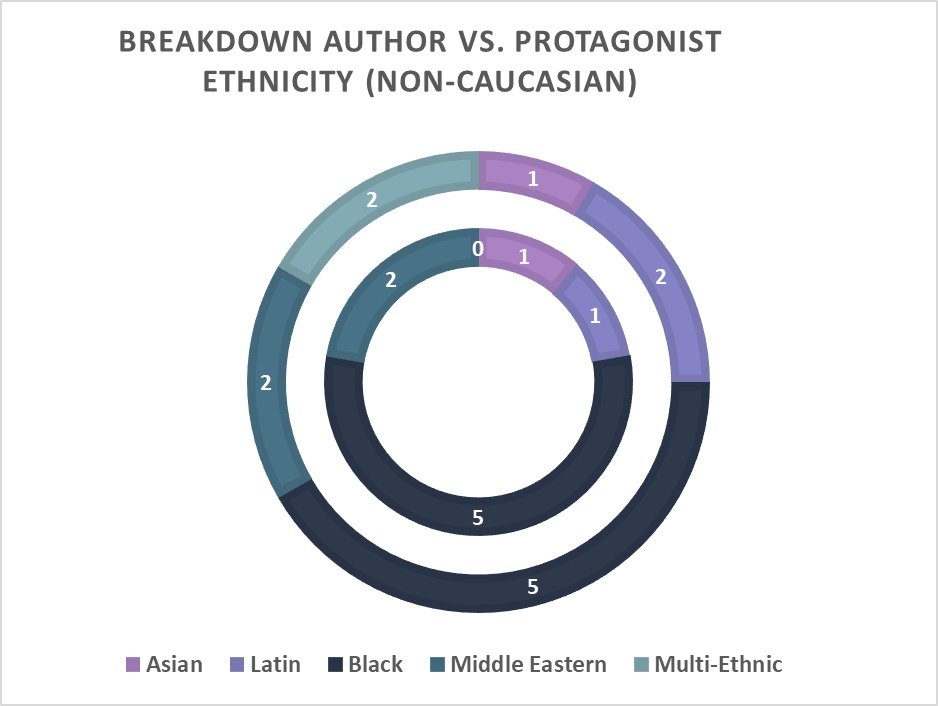

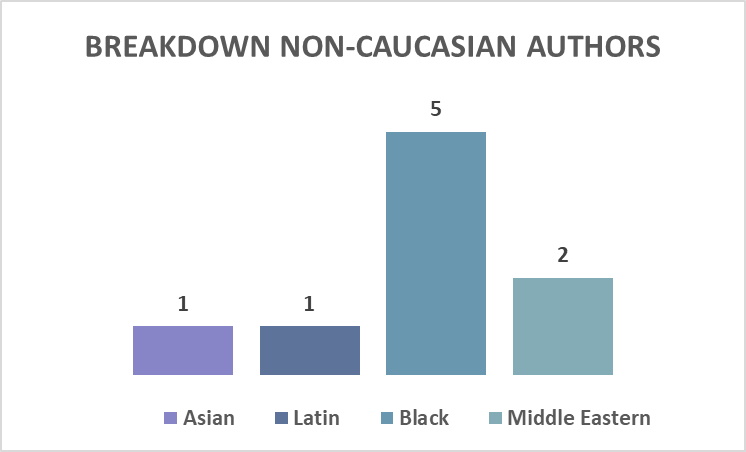

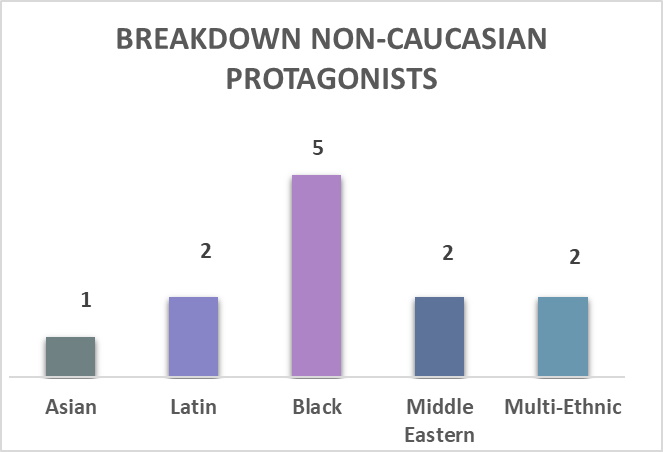

However, my Golden Age mystery binge also had a noticeable effect on the two statistics I'm tracking particularly: gender and ethnicity.

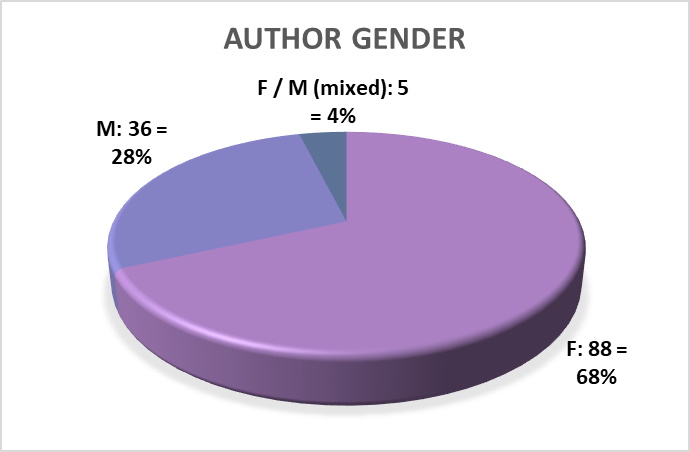

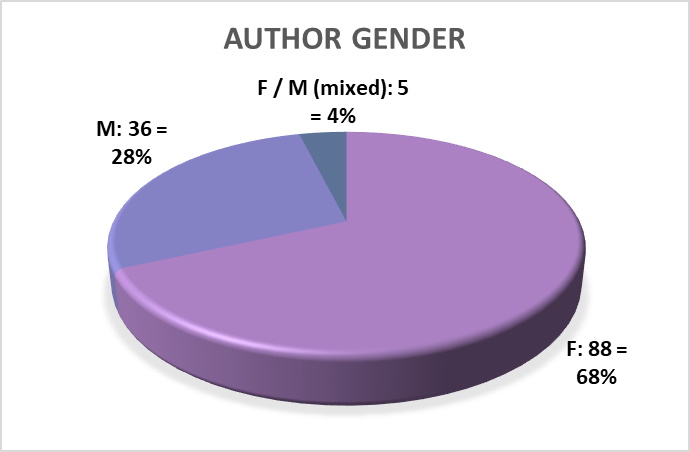

As far as gender is concerned things still look very good if you just focus on the authors: 88 books by women (plus 5 mixed anthologies / author teams) vs. 36 books by male authors; hooray! However, inspired by onnurtilraun, I decided to add another layer this time and also track protagonists ... and of course, if there is one genre where women authors have created a plethora of iconic male protagonists, it is Golden Age mystery fiction; and all the Miss Marples, Miss Silvers, Mrs. Bradleys and other female sleuths out there can't totally wipe out the number of books starring the likes of Hercule Poirot, Lord Peter Wimsey, Roderick Alleyn, and other male detectives of note. Then again, the Golden Age mystery novelists actually were ahead of their time in not only creating women sleuths acting independently but also in endowing their male detectives with equally strong female partners and friends, so the likes of Ariadne Oliver, Agatha "Troy" Alleyn, and of course the inimitable Harriet Vane, also make for a significantly higher number of books with both male and female protagonists. Still, the gender shift is impossible to miss.

(For those wondering about the "N / A" protagonist, that's Martha Wells's Murderbot, who of course is an AI and deliberately created as gender-neutral.)

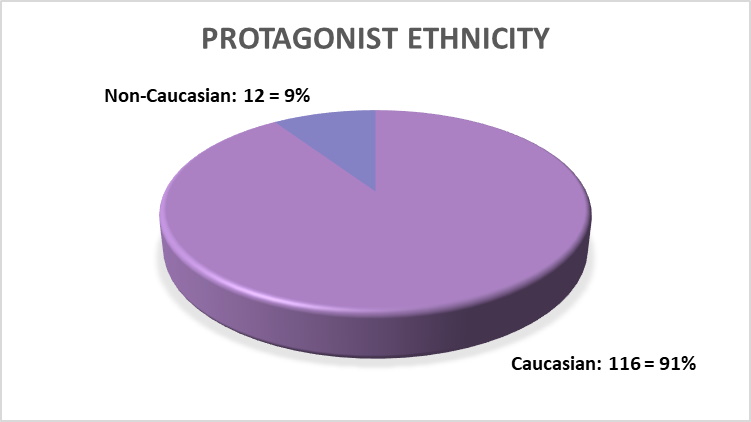

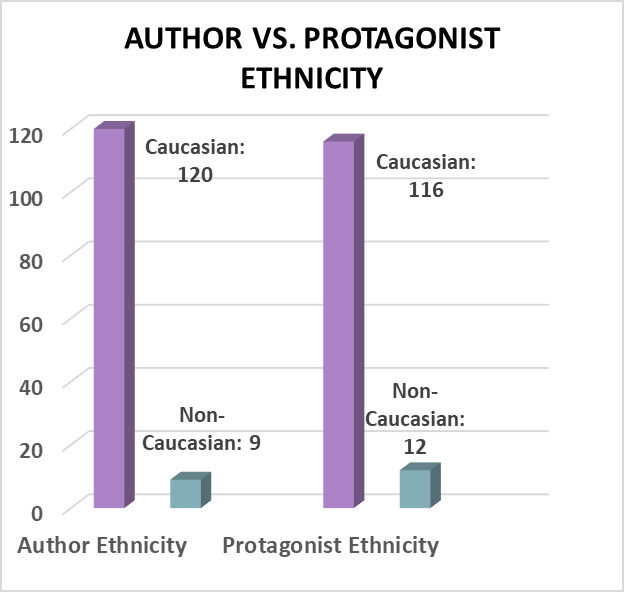

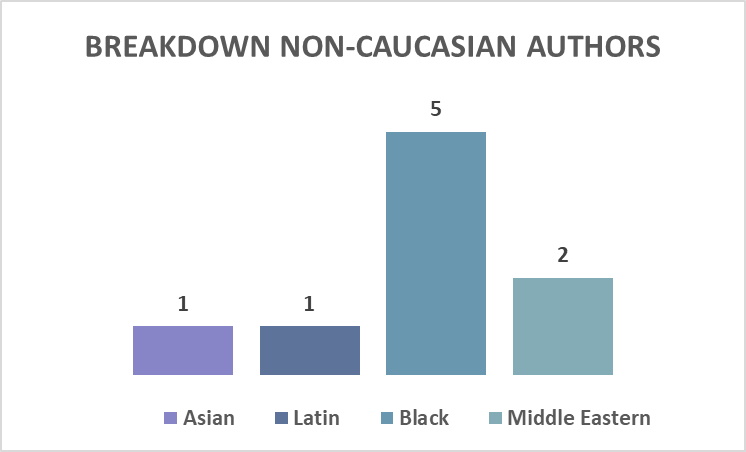

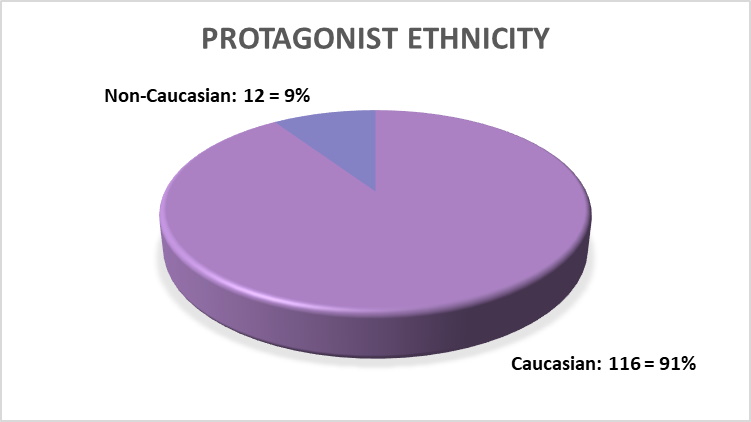

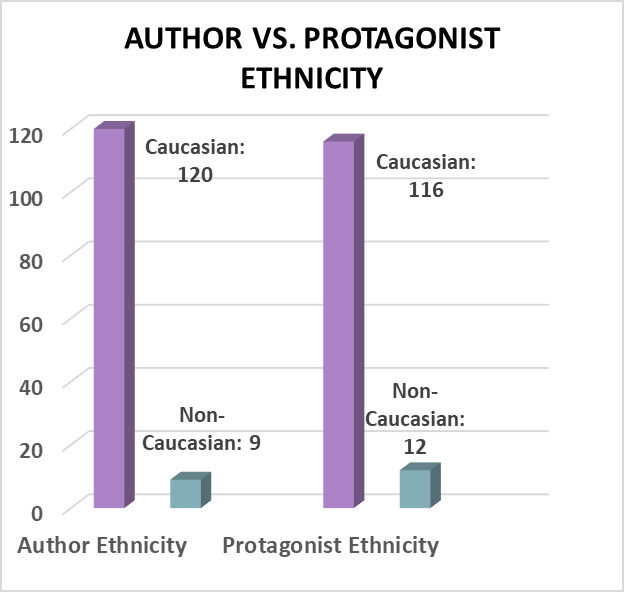

And of course, since there isn't a non-white author to be found among the Golden Age mystery writers (or at least, none that I'm aware of and whose books figured as part of my reading during the past couple of months), the ethnicity chart goes completely out of the window. Again, as long as you just look at the number of countries visited as part of my Around the World reading challenge (and if you ignore the number of books written by authors from / set in the UK and the U.S.), the figures actually still look pretty good -- and yes, the relatively high number of European countries is deliberate; I mostly focused on authors from / settings in the Southern Hemisphere last year, so I figured since tracking ethnicity was substantially impacted by the mystery binge this year anyway, I might as well make a bit of headway with the European countries, too.

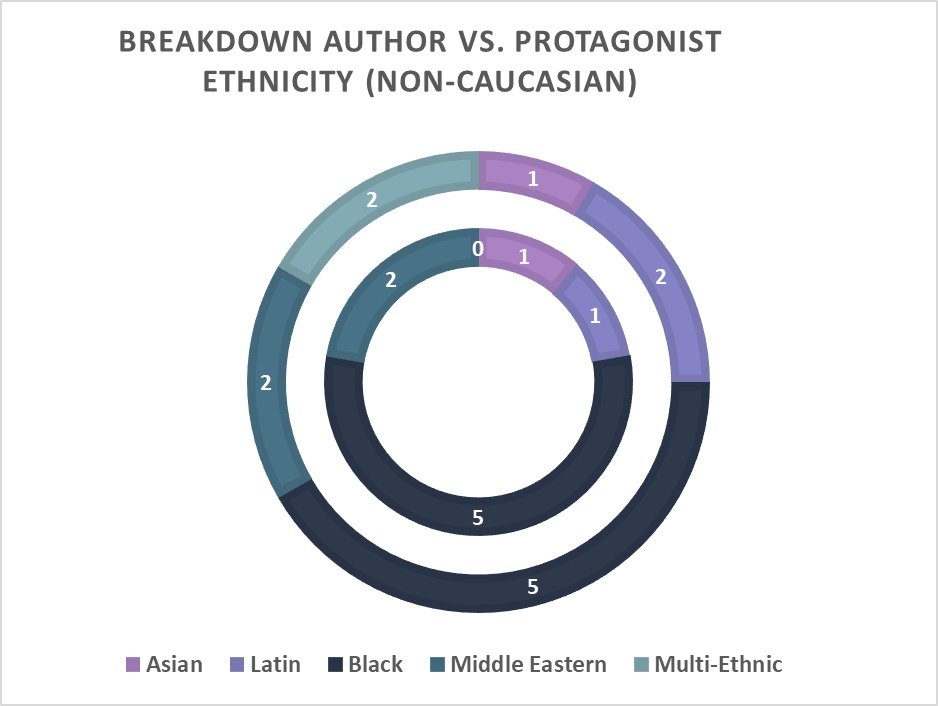

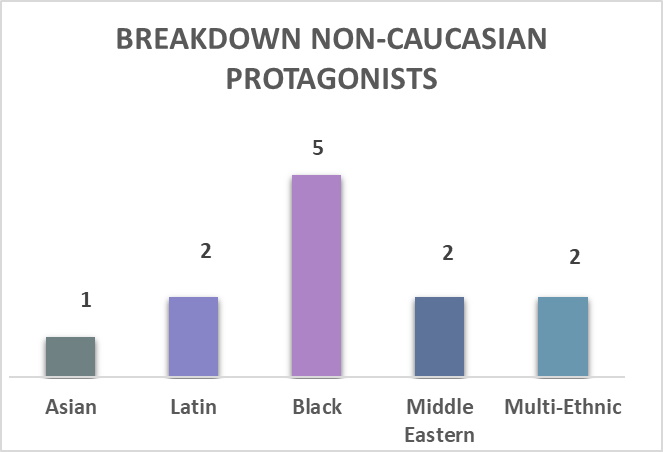

Yet, there is one interesting wrinkle even in the comparison of author vs. protagonist ethnicity; namely, where it comes to the non-Caucasian part of the table: It turns out that the number of non-white protagonists is slightly higher than that of non-white authors, because I managed to pick a few books at least which, though written by white authors, did feature non-white protagonists. Make of that one what you will ...

Nevertheless, for the rest of the year, the aim is clear ... catch up on my Around the World reading challenge and build in as many books by non-Caucasian authors as possible!

Log in with Facebook

Log in with Facebook

Saša Stanišić: Herkunft (Origin)

Saša Stanišić: Herkunft (Origin)