As I just finished the last book of Josephine Tey's Inspector Grant series (and have also read both of her nonseries mysteries, Brat Farrar and Miss Pym Disposes), it occurred to me that there is a third "series reading" master post I should keep, in addition to the First in Series and Ongoing Series posts that I created a while ago, as inspired by Moonlight Reader; namely, one to collect all my completed reading. So this post collects everything from books / series recently finished to those that I read a long time ago in a galaxy much further away than I care to think about: in the latter case, if fiction, I can't guarantee that I remember much about the plot or the characters (which just might mean that it's time for a reread, but that's a different matter); if nonfiction, whatever I remember of their contents has long merged into the general muddle of information about our world, past and present, that has passed through my brain over the years, mostly without taking permanent residence and definitely without me still being able to pinpoint any specific source. But so help me, I did read all of these -- some only once, some have become favorite comfort reads.

I'll only be collecting completed series or other similarly definable groups of books here (e.g., "all novels / short stories by ..."); beginning with actually completed books and concluding with a section listing the series I have abandoned. This is not intended as a master post listing all of my completed reading.

COMPLETED

MYSTERIES

Dermot Bolger

- Finbar's Hotel (ed.)

G.K. Chesterton

- Father Brown

Agatha Christie

- all mystery novels and short stories:

- Miss Marple

- Poirot

- Tommy & Tuppence

- Superintendent Battle (incl. Bundle Brent)

- Colonel Race

- Parker Pyne

- Qin & Satterthwaite

- Nonseries mysteries

Arthur Conan Doyle

- Sherlock Holmes

Michael Connelly

- Terry McCaleb

The Detection Club

- The Floating Admiral

Colin Dexter

- Inspector Morse

J. Jefferson Farjeon

- Inspector Kendall

Caroline Graham

- Midsomer Murders

George Heyer

- All mysteries:

- Inspector Hannasyde

- Inspector Hemingway

- Nonseries

Tony Hillerman

- Leaphorn & Chee

P.D. James

- Adam Dalgliesh

- Cordelia Gray

Stephen King

- The Green Mile

Stieg Larsson

- Millennium (original series)

Dennis Lehane

- Kenzie & Gennaro

Henning Mankell

- Wallander

Ngaio Marsh

- Roderick Alleyn

Denise Mina

- Garnethill Trilogy

George Pelecanos

- Derek Strange & Terry Quinn

Catherine Louisa Pirkis

- Loveday Brooke

Edgar Allan Poe

- Dupin Tales

Ian Rankin

- Jack Harvey Thrillers

Dorothy L. Sayers

- Lord Peter Wimsey (incl. Wimsey & Vane subseries)

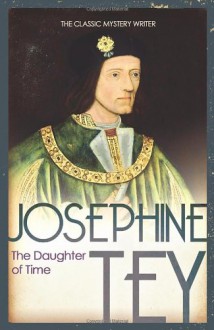

Josephine Tey

- All mysteries:

- Inspector Grant series

- Nonseries mysteries (Brat Farrar & Miss Pym Disposes)

HISTORICAL FICTION (ICNL. HISTORICAL MYSTERIES)

Robert van Gulik

- Judge Dee

Anthony Horowitz

- Sherlock Holmes sequels

John Jakes

- North and South Trilogy

Patrick O'Brian

- Aubrey & Maturin

Ellis Peters

- Brother Cadfael

David Pirie

- The Dark Beginnings of Sherlock Holmes

Jean Plaidy

- Mary Stuart

Tony Riches

- Tudor Trilogy

FANTASY / FAIRY TALES / SUPERNATURAL

Hans Christian Andersen

- Complete Fairy Tales

Brothers Grimm

- Complete Fairy Tales

Wilhelm Hauff

- Complete Fairy Tales

C.S. Lewis

- Chronicles of Narnia

Tamora Pierce

- Song of the Lioness

J.K. Rowling

- Harry Potter (minus The Cursed Child, which contrary to the sales hype wasn't actually written by Rowling)

J.R.R. Tolkien

- Middle Earth: The Hobbit & The Lord of the Rings

T.H. White

- The Once and Future King

Tad Williams

- Memory, Sorrow & Thorn

CLASSICS & LITFIC

Aeschylus

- Oresteia (Agamemnon / The Libarion Bearers / The Eumenides)

Louisa May Alcott

- Little Women (incl. Good Wives, Little Men & Jo's Boys)

Margaret Atwood

- Gilead (The Handmaid's Tale & The Testaments)

Jane Austen

- Novels and fragments (minus juvenalia, except for The History of England)

Gabriel Chevalier

- Clochemerle (Clochemerle & Clochemerle Babylon)

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

- Faust (Parts I & II and Urfaust)

Lewis Grassic Gibbon

- A Scots Quair

Robert Graves

- I, Claudius

- Books on Greek mythology (The Greek Myths; Greek Gods and Heroes)

Selma Lagerlöf

- Jerusalem

D.H. Lawrence

- Brangwen Family (The Rainbow & Women in Love)

Naguib Mahfouz

- Cairo Trilogy

- Novels & stories of Ancient Egypt (Khufu's Wisdom, Rhadopis of Nubia, Thebes at War, Akhenaten, Voices from the Other World)

Thomas Mann

- All novels and short stories

Edna O'Brien

- Country Girls Trilogy

William Shakespeare

- All plays, sonnets and short poems

Sophocles

- Theban Plays (Oedipus Rex, Oedipus at Colonnus, Antigone)

Wallace Stegner

- Joe Allston (All the Little Live Things & The Spectator Bird)

Anthony Trollope

- The Pallisers

HISTORY, (AUTO)BIOGRAPHY & OTHER NONFICTION

Will & Ariel Durant

- The Story of Civilization

Fischer Weltgeschichte

(various authors; elsewhere known as Universal History and Storia Unversale)

Antonia Fraser

- A Royal History of England (ed.)

Hugo Hamilton

- Childhood Memoirs

Hans J. Massaquoi

- Destine to Witness

Hans Silvester

- Cats in the Sun

ABANDONED

SERIES

Renée Ahdieh: The Wrath and the Dawn (after book 1, The Wrath and the Dawn)

Alan Bradley: Flavia de Luce (after book 1, The Sweetness at the Bottom of the Pie)

Dan Brown: Robert Langdon (after book 2, The Da Vinci Code; no other books from series read)

Miles Burton: Desmond Merrion (after book 1, The Secret of High Eldersham)

Trudi Canavan: Black Magician Trilogy (after book 1, The Magicians' Guild)

Zen Cho: Sorcerer to the Crown (after book 1, Sorcerer to the Crown)

Jennifer Estep: Crown of Shards (after book 1, Kill the Queen)

Helen Fielding: Bridget Jones's Diary (after book 1, Bridget Jones's Diary)

James Forrester: Clarenceux Trilogy (after book 1, Sacred Treason)

Elizabeth George: Inspector Lynley (after book 16, This Body of Death)

Lee Goldberg: Even Ronin (after book 1, Lost Hills)

Kerry Greenwood: Phryne Fischer (after book 1, Cocaine Blues, aka Miss Phryne Fisher Investigates)

Philippa Gregory: Tudor Court (after book 3, The Other Boleyn Girl; no other books from series read)

L.B. Hathaway: Posie Parker (DNF book 6.5, A Christmas Case; no other books from series read)

Martha Grimes: Richard Jury (after book 21, Dust)

Dorothy B. Hughes: Griselda Satterlee (after book 1, The So Blue Marble)

E.L. James: Fifty Shades (after book 1, Fifty Shades of Grey)

Carole Lawrence: Ian Hamilton (after book 1, Edinburgh Twilight)

Edward Marston: Christopher Redmayne (after book 1, The King's Evil)

Francine Matthews: Caroline Carmichael (after book 1, The Cutout)

Pat McIntosh: Gil Cunningham (after book 1, The Harper's Quine)

Stephenie Meyer: Twilight (after book 1, Twilight)

S.J. Parris: Giordano Bruno (after book 1, Heresy)

Louise Penny: Armand Gamache (after book 1, Still Life)

Elizabeth Peters: Amelia Peabody (after book 1, Crocodile on the Sandbank)

Valerie Plame Wilson & Sarah Lovett: Vanessa Pierson (after book 1, Blowback)

Patrick Senécal: Le vide (after book 1, Vivre au Max)

Helene Tursten: Inspector Irene Huss (after book 2, Night Rounds)

AUTHORS

Anne Rice

Read:

- Maifair Witches through book 2 (Lasher)

- Vampire Chronicles through book 6 (The Vampire Armand)

- Stand-alones: Cry to Heaven, Violin, Vittorio the Vampire

Log in with Facebook

Log in with Facebook

Tower of London: The round building center/left is the Bloody Tower, where King Edward IV's sons, today known simply as "the Princes in the Tower," are believed to have been held.

Tower of London: The round building center/left is the Bloody Tower, where King Edward IV's sons, today known simply as "the Princes in the Tower," are believed to have been held.