.... and I'm out.

This is insufferable.

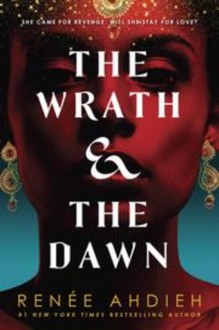

Granted, I'm not the target audience to begin with. But it's not even the concept of "1001 Nights as a YA love story" that is putting me off the most, even though that does have at least something to do with it. Shahrazād, in the original version, uses a potent brew of methods to get the king so wrapped up in her -- and her storytelling --, and a key element of that brew is seduction and sex appeal. Which I'm not seeing here at all, not even on the tamest "clean YA writing" level. We're repeatedly told that Shahrazad -- Western spelling, but let that be -- is "pretty" (or "beautiful"), and apparently the "boy king" she's gotten herself married to seems to be thinking so as well. BUT that doesn't deter him for a second from wanting to kill her straight at the beginning of the first night. Off which desire she temporarily manages to wean him by just batting her eyelashes and saying "Please grant me this one wish, before you kill me let me tell you a story??"

Which however brings us to the first thing that really sat wrongly with me straight from the start: motivation. As in, his, for letting her live -- past her first morning at that. We start off in the first night with the Thief of Baghdad, and by the time morning comes creeping in, we're just at the point where the Magic Lamp has been rubbed for the first time (not by Aladdin, either, in other words, just in case you'd been wondering). And just when some mysterious smoke begins to rise from the lamp, -- zing!!! -- Shahrazad offers up a cliffhanger and tells the king she can't possibly go on and she'll tell him the rest of the story tomorrow night. At which ... he's mildly annoyed but in short order agrees to let her live a little more, just like that, so he can listen to the ending of a story that doesn't even seem to have done more for him than amuse him on some level or other?! Sorry, but that's just ridiculous -- we're talking tyrant material here, after all.

Even more importantly, though: I could probably chog along with the book just fine if Adieh had taken the original collection's cue and kept from locating it all too firmly in reality. The original is a hodge podge of source material from all over the Orient, after all, very likely at least partly based on oral tradition and with none too firm and consistent a grasp on place names and time periods. And at heart, it's a collection of fairy tales. So what more proximate thing than to turn it into a fantasy tale, right? But what does Adieh do instead? She writes a historical novel ... without obviously having spent a single second on the historical and cultural research that such an approach requires. And there's only so much in terms of obvious errors and inconsistencies piling up within a very short time span that I am willing to take.

To stick with just a few of the "highlights":

Adieh bases her book in "Khorazan" -- let's assume that by this she means Greater Khorazan, which she may have settled on because the ruler whom Shahrazād marries in the original collection is characterized as a Sasanian king, and Khorazan, in the 7th century, swallowed up the Sasanian Empire. (Besides, it has the charm of having been a hotbet of Islamic culture with a rather lasting effect on all of the Middle East and Central Asia -- at least until the Mongols came calling.)

Now, my first problem with this is that she gives her boy king the official title of "caliph". Because NONE of the four caliphates whose territory included all or at least part of Greater Khorazan were ruled by a caliph residing (as this one does) in a city this far east. During the (earliest) Rashidun Caliphate it was Medina and Kufa (a city some 110 miles from present-day Baghdad); during the two caliphates with the largest territorial extension, the Umayyad and Abbasid Caliphates, it was successively Damascus, Harran, Kufa (again), Anbar, Baghdad, Raqqa, Samara, and Cairo, and during the (final) Ottoman Caliphate -- i.e., the Ottoman Empire -- it was several successive Turkish cities; with Constantinople / istanbul being capital for by far the longest time (but the Ottoman Empire no longer extended far enough east to begin with). The only thing Khorazan has to say for itself in terms of impacting the dynastic history of the caliphates is that the Abbasid Revolution started there (geographically and militarily / strategically speaking, that is).

Tl;dr: There never was a "Caliph of Khorazan" -- as Adieh, however, gives as her "boy king'"s title.

Again: If she hadn't written this as a historical novel (or indeed, as any sort of book set in the real world), that wouldn't be a problem. Since she insists on giving specific historic and geographical details, however, readers such as me expect her to have done her homework and verified that at least the major elements of her story are consistent with historic fact and reality. This one isn't.

Now: Since Adieh has Shahrazad start with the story of the Thief of Baghdad, obviously Baghdad has to exist at the time in which her book is set. Which puts us into the time of the Abbasid Caliphate, as it was the Abbasides who founded Baghdad (and the Ottomans no longer ruled over Khorazan, see above). And if we look at the extension of the Abbasid Caliphate, we see that although it still extends fairly far to the west in northern Africa, it no longer covers Morocco / the Maghreb, nor any part of Spain. Why is that important? Because Adieh refers to someone as "a Moor" and, in the same breath, tells us that he is "from Spain". Which is consistent insofar as much of Spain remained Islamic after the Abbasids had expelled the Umayyads; in fact it was to the Caliphate of Córdoba that the Umayyads retrenched upon being kicked out of the rest of their territory. HOWEVER, during that time period no self-respecting Muslim would have referred to a Muslim from Spain as "a Moor"; at least not, simply by way of an introduction or explanation as it is done here. To begin with, this term (or "Mauri") merely referred to the Maghreb (= North African) Berbers, not also people from Spain; indeed, people from the Maghreb region in northwestern Africa are still referred to as "Mauri" by 16th century scholar Leo Africanus. More importantly, however, in the Middle Ages "moor" ("moro" / "mouro" in Spanish and Portuguese) was a derogative term used by the Christians during the Reconquista and the Crusades. It was a racist slur -- nothing short of the "N"-word of the Middle Ages.

Tl;dr:

Words are important. They are to your readers -- and they should be to you as a writer as well. Obviously, they aren't. That is a pity.

And speaking of words (and titles / addresses): A little later, someone is addressed as "effendi". That, in turn, is a form of address that was not used as far east as Khorazan at all -- it is a classic expression of respect used almost at the other end of the world as far as a resident of Greater Khorazan would have been conderned: in the Eastern Mediterranean of the Byzantine and Ottoman Empires. Which just might still make sense as the gentleman in question does not currently reside in Khorazan -- the problem is, however: He used to. In fact, he used to be tutor and confidant to our "boy king"'s mother practically forever (until he was kicked out by the seat of his pants). Which makes him just about anything by way of a respectful address from another Khorazani (none other than Shahrazad herself), but certainly not "effendi".

Tl;dr: See above -- words matter. Do your godd**n research, woman. Turks would address someone as "effendi" -- not Khorazans.

And literally within a few pages of the above, we learn that another young gentleman from Khorazan, in seeking support for a campaign he's mounting, is riding out to "the Badawi" -- i.e., the Bedouins. Which again would all be fine and dandy, the extent of the Abbasid Caliphate being what it was, if the next thing we'd be hearing about would be a weeks-, if not months-long trip fraught with hardship, mastered with the help of only a single horse for transport (in fact, way too good a horse to risk its health on such a trip, but let that go). But no -- he has no sooner spoken of seeking out the Badawi than he's already chatting to one of them next to a well.

At which point the story, quite literally, had hit the bottom of the well for me once and for all.

One more time: If Adieh had given me the slightest indication that she doesn't mean her book to be set in the real world -- in its past -- I'd have gone along with her. (Not quite willingly as her writing isn't exactly stellar, either, but at least I'd have finished the book.) But since she insists on peppering it with real world historic references, she must expect to be measured by the standards that such references invite. And measured by those standards, her book falls woefully short on just about every page. None of which has anything to do with this being a YA book -- YA readers have just as much of a right to be offered historically well-researched books as anybody else. (Incidentally: in this post, I'm deliberately only linking to Wikipedia pages, because that shows just how little effort it would have taken on Adieh's part to at least get a handle on the core basics.)

Side note: Ariana Delawari as a narrator goes straight onto my "never again" list, too. I've tried my hardest not to attribute her shortcomings to the author in addition to Adieh's own blunders, but Delawari's narration certainly didn't make up for the writing, either.

So, I'll pocket my $2 for BL-opoly and move straight along ... fortunately, at least today is another roll day for me!

Log in with Facebook

Log in with Facebook