Today my sister and I sat down to talk about a book by a Polish writer, literary critic, university professor and a feminist. Below you will find the transcript shabbily translated from Polish by me.

Kinga: Some time ago I asked you: Basia, do we like that Inga Iwasiów or not? And you told me that we didn’t have an official position on that yet and then you went and bought me ‘Blogotony’ which we read together. What are your impressions?

Basia: ‘Blogotony’ consists mostly of Inga Iwasiów’s blog published in a book form. It’s hard to describe my feelings about it in one word, because, as usual with different collections, I was taken in by some chapters and irritated by others. However, if you asked me now if we like that Inga Iwasiów , I would tell you that we do.

Before we proceed to talk about the book in detail and the reasons why I decided for both of us that we like Ms Iwasiów, I wanted to ask you if you think publishing an Internet blog in a book form makes sense?

Kinga: I suppose you can say, it doesn't make sense, because it’s all already been published on the internet so what’s the point? However, I dare to say that a book is a slightly more mainstream product and, in a way, it elevates the blog. Anyone can write a blog, but a book published by an established publisher is only achieved by some. A blog in book form is like a seal of approval and, of course, it’s another (tiny) revenue stream for our forever broke Polish men and women of letters. On the other hand, there is a problem with such a book because a blog, by its nature, describes everything as it happens, and without its temporal context it might appear undecipherable and in need of footnotes.

Basia: Indeed. I agree with you about publishing things earlier available on the internet. They say nothing is ever lost on the internet but why tempt fate?

Some time ago W.A.B. published Jacek Dehnel’s essays, which can be easily found online, but I’m happy they've been published in a book form. The problem with ‘Blogotony’ is that they are not essays but your typical blog posts, often commenting on current events, and some of them long past their due date, like the one talking about the rape joke about a Ukrainian cleaner spoken on air by Figurski and Wojewódzki. The issue which Iwasiów writes about will sadly be valid still for a long time, but here it appears as a comment on a micro-event which won’t be remembered a few years from now, and I assume while reading a book you don’t want to have to go on the internet all the time to understand what’s going on. That’s why I think the book would’ve been a lot better if the author implemented some changes in the text before publishing it.

But since we are talking about that post about Wojewódzki and Figurski, I’d be interested to know what you think about it. Do you agree with the author that there was nothing funny about it or do you think that maybe there is some truth to the stereotype that ‘feminists don’t have a sense of humour, especially if they are the butt of a joke’?

Kinga: Feminists have an amazing sense of humour, a case in point being that they don’t find Wojewódzki and Figurski’s jokes funny. The issue here is the kind of humour. I expect more originality and finesse from my comedians than just spitting out crass, done-to-death, sexist lines. Maybe one day, when sexism in Poland stops being such a pressing issue we will be able to make jokes about it. Right now those are not funny because they are just too close to the sad reality. For the same reason I don’t find funny jokes about Slavic girls, who are Poland’s main ‘natural resource’ and ‘most precious export product’ (vide: Polish Eurovision entry this year), because human trafficking of women from Eastern Europe is a real issue and I’d rather we didn't reinforce the stereotypes that Slavic women are a commodity.

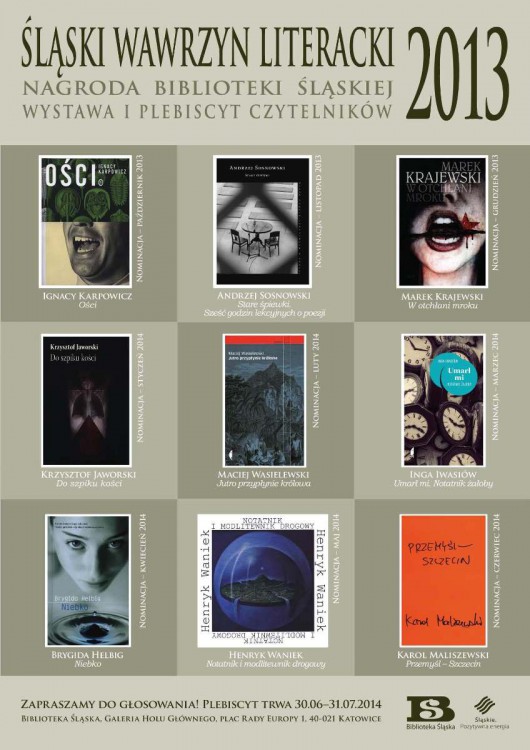

Anyway, feminism in Poland is still strange. I have lived abroad long enough to forget that in Poland educated men and women are still using the word ‘feminist’ as an insult so they distance themselves from it just in case. Here, I would say the majority of my friends of both sexes would call themselves feminists. Before our conversation I read a few reviews of ‘Blogotony’ on the internet and almost every one of them mentioned in the beginning that Iwasiów is a writer, university professor, literary critic, but also…, and here a pregnant pause, a feminist. As if Iwasiów were a hermaphrodite unicorn. And obviously in the next paragraph the reviewers would reassure their worried readers that they were not feminists themselves, they disagreed with feminist views but generally they praised the book. In none of those (rather uninspired) reviews did I find a single mention of any of those revolutionary views that the reviewers disagreed with.

Basia: Maybe those from the post where Iwasiów explains why she thinks reading romance novels can be harmful, even modern ones, or maybe especially those, because while we know exactly what to expect from Monika Szwaja or Małgorzata Kalicińska, some younger authors fool us with their liberated, independent heroines, while really presenting a distorted image of male-female relationships.

to cut it short, the fact that women are cunning and men are childish. […] Because men are never good, and being a housewife is terrible, it is necessary to use some mythical female potions and con men. There is no room for understanding, openness, dialogue, community. In this narrative men and women really do come from different planets, they are enemies, but they have to (I feel so sorry for them!) live together. […] Ladies, luckily, have their little ways. They never forget to put make up on, the bra strap […] Brrr! Just thinking about such a life, where you can’t tell your life partner the truth […], you always have to act, always look pretty […] fills me with dread. […] Men and women fit together only anatomically, and manipulation is the only way for both sexes to co-exist.”

Maybe those women who declare they are not feminists because it’s repulsive to them prefer to live in a world where there is a never-ending war between sexes because we come from different planets.

Kinga: I really find it hard to believe that any emotionally mature person would want to play such games. That constant strategising to fool the other person, bend them to your will. Many men (as well as women) like to accuse feminists of starting some war with men, which is total nonsense. It’s the feminists who want to be equal partners to their men, they want to play on the same team. I feel that people with limited and superficial interests are more prone to such dysfunctional antagonistic attitudes. If he only cares about football and beer, and she only likes chocolate ice-cream and shoes, then it’s easier for them to get involved in such a guerrilla war, because they have no common ground they could meet on. Additionally, all this insisting on what men and women should be interested in has a negative impact on their ability to communicate with each other, because it reinforces that idiotic notion that we are so different from each other that we need manuals and articles in magazines to learn how to deal with one another. This is what feminists are trying to fight against and it should be in everyone’s interest that they win.

Basia: So this is what we agree with Iwasiów on. And what didn’t you like?

Kinga: I disagree with Iwasiów in her vendetta against pop culture. Of course, there are many aspects to it I don’t like, but let’s not throw the baby out with the bathwater. Iwasiów says “I believe, however, that feminism today has more to lose than to win from its flirting with popculture”. I don’t think that’s true. But then Iwasiów and I have a very different vantage point – she treats feminism as an academic discipline and my approach is more pragmatic – I actually want to change the world (yeah, still haven’t outgrown that). And to change the world you need to appeal to it and speak its language. Another thing is that I find it really hard to divide all cultural production into two camps: high culture and pop culture. It’s all fluid and more of a spectrum than a dichotomy. That is not to say I am ok with the degradation of high culture and I agree with Iwasiów that the intellectual effort required to commune with is an important value but I would focus on promoting the pleasure that effort brings. Just like physical effort, intellectual effort can bring pure, almost hedonistic pleasure.

Basia: I agree with you to an extent but I also understand that Iwasiów’s view is coloured by the frustration of someone whose students insist on discussing ‘Dom nad rozlewiskiem’* in class and I feel we are also giving up too easily. I have seen different campaigns in defense of bad romance novels, because it’s supposedly better if Polish people read that than nothing at all. I’m really not sure it’s like that – that you start from ‘Dom nad rozlewiskiem’ and then evolve towards Faludi’s ‘Backlash’ .

What I didn’t like, though, was that occasionally the author, who insisted people stop using stereotypes, was using them herself, like when she was judging elegant women on business trips to be the ones who would never read her books. And it’s not like that. I used to be one of those women from corporations, not because that was what my heart told me to do, but because that was what life made me do. So I feel like on this occasion Iwasiów lacks some sensitivity and humility.

Kinga: Yes, I was struck by that as well, because, it’s worth mentioning, I’m conducting this conversation with you from a company laptop from a company flat, where I live temporarily while shuttling between London and Scotland, carrying Iwasiów’s ‘Na krótko’ in my suitcase. Of course, I dream of a life like the kind Iwasiów leads, but things just didn’t work out that way. I feel that Iwasiów inhabits a world drastically different from ours. She even admits that herself, and I suppose she finds it hard to believe that that her works could make it over to the other side. But she shouldn’t worry because they find us here just fine.

Just as a quick after note about some other things I liked about the book – it’s of course our idee fixe – women in literature. Iwasiów doesn’t say anything new about the problem, but why should she if the old problem is still unsolved. Men’s stories are universal, and women’s stories are women’s. I really liked this quote:

“The blood of childbirth, the blood of menstruation can only cause condescending smirks. It’s hard to call this a blood taboo because in our world of birth and tampon ads, no one is still seriously perpetuating the myths about the impure nature of women. Female blood is simply trivial, unworthy of poems or novels. Unlike male hangovers.’

Of course we only touched on a slice of subjects discussed by Iwasiów, because it would be impossible to go through them all. We would need to be talking for two days and we have to go to work tomorrow, so let me just end this with a reiteration that our official position on Iwasiów is that we like her.

* Dom nad rozlewiskiem - (tr. House by a Marsh) is a sappy uber-successful Polish novel about a woman who escapes the city and moves to a village in a lake region, where I assume she finds love and happiness. I have only managed to read two pages because the writing was absolutely dreadful. It has also been turned into a very bad TV Series.

Log in with Facebook

Log in with Facebook