Irving visits Alcala de los Panaderos ("Town of Bakers"), an area that once supplied most of Seville's bread supply. The area is now called Alcala de Guadaira, or "river valley". As if I didn't get hungry enough from him talking about the "Town of Bakers" {fresh bread mmmm... oh, sorry} Irving goes on to talk about his breakfasts of "chocolate con leche y bollos para almuerza" or chocolate milk and sugar cakes. Not particularly nutritious, I know, but sounds like some tasty comfort food, good for a lazy Sunday morning.

Speaking of river valleys, Irving also takes in the impressive sight of Roman-Moorish aqueducts - it amazes me that these structures still stand today! He also mentions touring "masmoras" or what he describes as "subterranean granaries", which confused me since I thought the word "mazmorra" translated to "dungeon"? I guess the space could function as either, really...

aqueduct in Roman-Moorish style

aqueduct in Roman-Moorish style

Masmora or Mazmorra??

One concern I have of overseas travel that even Irving ran into in his day was that of thieves. Today, one primarily thinks of pickpockets on crowded streets, but in the 1800s, a person still feared a run-in with smugglers and your sort of all-purpose thieves. Funny though, Irving comments that these "unsavory characters" as we might think of them now "had risen to be a kind of mongrel chivalry in Spain", sounding something like the Robin Hood of legends. There was even the custom of the "robber's purse" (carried with the expectation that you could very likely be robbed, sort of a decoy bag) which from the description made me laugh, but I could sort of see a purpose for in today's world!

"As our proposed route to Granada lay through mountainous regions, where the roads are little better than mule-paths, and said to be frequently beset by robbers, we took due travelling precautions. Forwarding the most valuable part of our luggage a day or two in advance by the arrieros (person that handles the pack mules), we retained merely clothing and necessaries for the journey and money for the expenses of the road; with a little surplus of hard dollars by way of robber purse, to satisfy the gentlemen of the road should we be assailed. Unlucky is the too wary traveler, who, having grudged this precaution, falls into their clutches empty-handed; they are apt to give him a sound rib-roasting for cheating them out of their dues. Caballeros like them cannot afford to scour the roads and risk the gallows for nothing."

A number of the legends and stories Irving shares with his readers were told to him by the numerous characters he and the prince would come across on their travels. One such is adorably described as "a pursy little man shaped not unlike a toad and mounted on a mule". That description just immediately makes me think of some detailed painting that might show up in a child's storybook! These memorable characters they meet along the road are only too willing to share the stories of Granada and the Alhambra. In fact, it is through them that Irving is able to piece together much of the history he transcribes. As he puts it:

I have remarked that the stories of treasure are most current among the poorest people. Kind nature consoles with shadows for the lack of substantials. The thirsty man dreams of fountains and running streams; the hungry man of banquets; and the poor man heaps of hidden gold : nothing certainly is more opulent than the imagination of a beggar.

By the way, one of the legends of hidden treasure in and around the Alhambra was that of a magical violin, which Irving claims is the very same violin that skyrocketed classical violinist Paganini to superstardom in his day.

Another thing I noticed - Irving and the prince seemed to be able to pay for anything (that they didn't have or didn't want to use money for) with cigars! They seemed to be handing them out left and right to anyone they might get a story out of! Either there was some money flowing about between them or cigars were quite a bit cheaper back then ... or they were just giving out the cheap stuff :-P

Moors living in Granada at the time of the palace's construction swore that the royals must surely have been practicing alchemy to come up with the gold it must have cost to build such a structure. Even then, the people of Granada saw the dreamlike quality of the architecture. As Irving said:

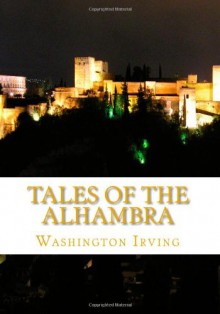

Such is the Alhambra; -- a Moslem pile in the midst of a Christian land; an Oriental palace amidst the Gothic edifices of the West; an elegant memento of a brave, intelligent, and graceful people, who conquered, ruled, flourished and passed away.

Many of the legends involve the Moorish king Boabdil. He doesn't have the best rep in Moorish history but Irving claims that is largely due to wrongfully being labeled a tyrant, the most damning accounts coming from a largely fictionalized history book entitled The Civil Wars of Granada. Boabdil was the eldest son of two first cousins, and went on to marry Morayma, the daughter of legendary Spanish soldier, Ali Atar, who served during the time of Ferdinand and Isabella. If you're interested, you can read the all about the details of this family here. Ferdinand and Isabella actually requested to be buried at the Alhambra but instead they were entombed at the nearby chapel, as their counselors did not believe it proper for them to be buried in a Muslim fortress, the royal couple being Catholic themselves.

One ruler, Alhamar, the man the fortress was named after, did quite a bit to improve living conditions of Granada. During his reign, he set up a police department, had a hospital for the poor and / or disabled built (and, even more impressively, he would do unannounced visits to the hospitals to make sure patients were being treated well!), developed schools, colleges, public baths, aqueducts and irrigation systems, set up silk manufacturing in the area, increased gold and silver mining jobs, and , probably because of all this, was the first king of Granada to have his face put on the currency of the day. Sadly, Alhamar met a bizarre end:

Alhamar retained his faculties and vigor to an advanced age. In his 79th year, (A.D. 1272), he took the field on horseback, accompanied by the flower of his chivalry, to resist an invasion of his territories. As the army sallied forth from Granada, one of the principal adalides, or guides, who rode in the advance, accidentally broke his lance against the arch of the gate. The counselors of the king, alarmed by this circumstance, which was considered an evil omen, entreated him to return. Their supplications were in vain. The king persisted and at noontide the omen, says the Moorish chroniclers, was fatally fulfilled. Alhamar was suddenly struck with illness and had nearly fallen from his horse. He was placed on a litter, and born back towards Granada, but his illness increased to such a degree that they were obliged to pitch a tent in the Vega. His physicians were filled with consternation, not knowing what remedy to prescribe. In a few hours he died, vomiting blood and in violent convulsions. The Castillian prince, Don Philip, brother of Alonzo X, was by his side when he expired. His body was embalmed, enclosed in a silver coffin and buried in the Alhambra in a sepulchre of precious marble amidst the unfeigned lamentations of his subjects who bewailed him as a parent.

There are also stories here, such as "Legend Of Prince Ahmed Al Kamel, or The Pilgrim of Love" and "The Legend of the Moor's Legacy" which echo elements of such fairytales as Aladdin and his Cave of Wonders. Items and people are enchanted and trapped for all eternity or until curses are completely broken, but every year on the eve of the festival of St. John, enchantments can be broken for one night by those wearing magical talismans. There is one quote especially that sums up my impression in not only reading this book but my love for books in general:

In present day, when popular literature is running into the low levels of life and luxuriating on the vices and follies of mankind; and when the universal pursuit of gain is trampling down the early growth of poetic feeling, and wearing out the verdure of the soul, I question whether it would not be of service for the reader occasionally to turn to these records of prouder times and loftier modes of thinking; and to steep himself to the very lips in old Spanish romance.

Irving went on to serve as the US Ambassador to Spain from 1842-1845, before retiring to Sunnyside, his estate in the Hudson Valley area of New York. Sunnyside also became a sort of retreat for other writers during Irving's lifetime. After his passing, Irving was buried at nearby Sleepy Hollow cemetery.

History mingles with legends and myths quite a bit in this work, which, when mixed with Irving's compelling writing style, makes this such an entertaining read for history junkies.

Log in with Facebook

Log in with Facebook

The Alhambra in Granada, Spain

The Alhambra in Granada, Spain

Matilda Hoffman

Matilda Hoffman