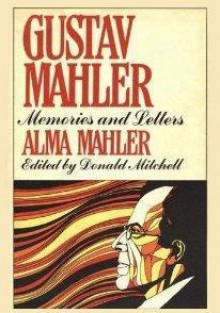

As beautiful, highly educated and endowed for the arts as Alma Mahler-Werfel (1879-1964) was, she could have achieved a lot in the world, but during most of her life she remained in the shadows of her famous husbands and lovers. She had the bad luck to have been born at a time, when women only made their first tentative steps to claim their rights and their own place in society. Although her family and the circles that they frequented were among the most liberal of the fin de siècle, young and shy Alma quite naturally obeyed the command of her much older first husband Gustav Mahler (1860-1911) to give up for good all her own musical ambitions and activities. In 1939, when the Nazi regime defamed his work because he had been a Jew converted to Protestantism and refused him his place in the world of music, she brought out her very personal tribute to him under the title Gustav Mahler. Memories and Letters.

Alma Mahler-Werfel begins her largely admiring memories of her late husband with their first encounter at a dinner party in November 1901. Although frequenting the same circles, until then she had managed to avoid meeting the controversial conductor and composer Gustav Mahler against whom public opinion and malicious gossip had biased her. Moreover, Alma had been to a performance of his First Symphony and – like most music lovers of the time – she loathed it because even she as a student of composition couldn’t understand his modern approach. However, the middle-aged musician was immediately attracted to the young woman and quite naturally she was impressed by the man and flattered by his attentions. Passionate and used to getting what he wanted, Gustav Mahler didn’t take long to make Alma his bride and he expected of her no less than giving up her own life as well as identity. For her it was a great sacrifice to abandon her music studies and composing, but she was convinced that it was worth it. And she never lost this conviction although she acknowledges to have been too young as well as too inexperienced and romantic to have known better. On their wedding day in March 1902 – scarce four months after their first encounter – Alma was already with child, but her condition changed nothing. He and his needs were all that counted even after their daughter was born and then another daughter. She never once reproached him for his egotism and lack of regard for her because she felt that as a musical genius he stood so much above her. Besides, she was aware that he needed the stability of home and her support since he had to cope with opposition from all sides – for his Jewish descent, for his modernist understanding of music, and for his tempers and idiosyncrasies. At the cost of her own health, she stayed by his side on his travels until his untimely death in May 1911.

Every word of Alma Mahler-Werfel shows her unshakable awe of her ingenious husband and of his music although she didn’t go far beyond summarising the facts of their life together. I can’t help thinking that she left out quite a lot in order to paint as positive a picture of the man Gustav Mahler as she could. Maybe this was also due to her innate reserve and delicacy. It seems that she wasn’t actually a woman who wished to spread out her private life in public and in the foreword from 1939 she says herself that she hadn’t intended to publish her memories of Gustav Mahler or his letters to her during her lifetime. Seeing the Nazi regime talking ill of her late husband and denying his musical genius urged her to bring out the book in the dawn of World War Two. Although her portrait is necessarily biased and moreover incomplete, Gustav Mahler. Memories and Letters by Alma Mahler-Werfel is a partly forgotten read that definitely deserves my recommendation.

Gustav Mahler: Memories and Letters - Alma Mahler-Werfel,Donald Mitchell,Knud Martner Gustav Mahler (German Edition) - Alma Mahler-Werfel

The Austrian by J.O. Mantel

The Austrian by J.O. Mantel

Log in with Facebook

Log in with Facebook