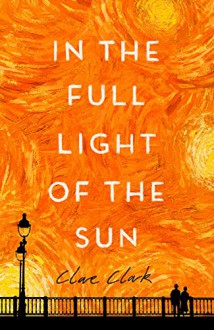

Thanks to NetGalley and to Virago for providing me an ARC copy of this novel and allowing me to participate in the blog tour for its launch. I freely chose to review it, and I’m very happy I did.

I am sure you will have noticed the beautiful cover and it might give you a hint of what the book is about. Yes, the book is about Vincent Van Gogh; well, about his art and his paintings, and the controversy that followed the sale in Germany in the 1920s of some of his paintings, which later were identified as fakes (well, perhaps, although the controversy about some of Van Gogh’s paintings, even some of the best-known ones, has carried on until the present). But that is not all.

The story is divided into three parts, all set in Berlin, each one narrated from one character’s points of view, and covering different historical periods, although all of them in the interwar era and told in chronological order. The more I thought about it, the more I felt that the author had chosen the characters as symbols and stand-ins for each particular part of that period of the history of Germany they represented. By setting the story in the 1920s and 30s, in the post-WWI Germany, we get immersed in a rapidly changing society, and one whose political developments and social unrest share more than a passing similarity with some of the things we are experiencing internationally nowadays.

The first part, set in Berlin in 1923, is told in the third-person from the point of view of Julius Köhler-Schultz. He is an art expert, collector, has written a book about Van-Gogh, and is going through a difficult divorce. But he is much more obsessed with art and preoccupied about his artworks than he is about his family. This is a time of extreme inflation, where German money is so devaluated that it is worth nothing, and the comments about it reminded me of a photograph of the period I had seen not long ago where children were playing in the streets with piles of banknotes, using them to build walls, as if they were Lego bricks. As the novel says:

“The prices were meaningless —a single match for nine hundred million marks — and they changed six times a day; no one ever had enough. At the cinema near Böhm’s office, the sign in the window of the ticket booth read: Admission –two lumps of coal.”

This section of the book establishes the story, and introduces many of the main players, not only Julius, but also Matthias, a young man Julius takes under his wing, who wants to learn about art and ends up opening his own gallery; and Emmeline, a young girl who refuses to be just a proper young lady and wants to become an artist. Julius is an intelligent man, very sharp and good at analysing what is going on around him, but blind to his emotions and those of others, and he is more of an observer than an active player. His most endearing characteristic is his love and devotion for art and artists, but he is not the most sympathetic and engaging of characters. He is self-centred and egotistical, although he becomes more humanised and humane as the story moves on.

The second part of the novel is set in Berlin in 1927, and it is told, again in the third-person, from Emmeline Eberhardt’s point of view. Although we had met her in the first part, she has now grown up and seems to be a stand-in for the Weimar Republic, for the freedom of the era, where everything seemed possible, where Berlin was full of excitement, night clubs, parties, Russian émigrés, new art movements, social change, and everything went. She is a bit lost. She wants to be an artist, but does not have confidence in herself; she manages to get a job as an illustrator in a new magazine but gets quickly bored drawing always the same; she loves women, but sometimes looks for men to fill a gap. She can’t settle and wants to do everything and live to the limit as if she knew something was around the corner, and she might not have a chance otherwise. Although she gets involved, somehow, in the mess of the fake paintings (we won’t know exactly how until much later on), this part of the story felt much more personal and immediate, at least for me. She is in turmoil, especially due to her friendship with a neighbour, Dora, who becomes obsessed with the story of the fake Van Goghs, but there are also lovely moments when Emmeline reflects on what she sees, and she truly has the eye of an artist, and she also shares very insightful observations. I loved Dora’s grandmother as well. She cannot move but she has a zest for life and plenty of stories.

“When Dora was very little her governess put a pile of books on her chair so she could reach the table but Dora refused to sit on them,’ Oma said. ‘Remember, Dodo? You thought you would squash all the people who lived inside.’”

The third part is set in Berlin in 1933 and is written in the first person, from the point of view of Frank Berszacki. He is a Jewish lawyer living in Berlin and experiences first-hand the rise to power of the Nazis. He becomes the lawyer of Emmeline’s husband, Anton, and that seems to be his link to the story, but later we discover that he was the lawyer for Matthias Rachman, the man who, supposedly, sold the fake Van Goghs, the friend of Julius. As most people who are familiar with any of the books or movies of the period know, at first most people did not believe things would get as bad as they did in Germany with Hitler’s rise to power. But things keep getting worse and worse.

“I want to know how it is possible that this is happening. It cannot go on, we have all been saying it for months, someone will stop it, and yet no one stops it and it goes on. It gets worse. April 1 and who exactly are the fools?”

His licence to practice is revoked, and although it is returned to him because he had fought for Germany in the previous war; he struggles to find any clients, and the German ones can simply choose not to settle their bills. He and his wife have experienced a terrible loss and life is already strained before the world around them becomes increasingly mad and threatening. When his brother decides to leave the country and asks him to house his daughter, Mina, for a short while, while he gets everything ready, the girl manages to shake their comfortable but numb existence and has a profound impact in their lives.

Although I loved the story from the beginning, I became more and more involved with the characters as it progressed, and I felt particularly close to the characters in part 3, partly because of the first-person narration, partly because of the evident grieving and sense of loss they were already experiencing, and partly because of their care for each other and the way the married couple kept trying to protect each other from the worst of the situation. I agree that not all the characters are sympathetic and easy to connect with, but the beauty of the writing more than makes up for that, as does the fascinating story, which as the author explains in her note at the end, although fictionalised, is based on real events. I also loved the snippets from Van Gogh’s letters, so inspiring, and the well-described atmosphere of the Berlin of the period, which gets more and more oppressive as it goes along. I found the ending satisfying and hopeful, and I think most readers will feel the same way about it.

This is not a novel for everybody. It is literary fiction, and although it has elements of historical fiction, and also of the thriller, its rhythm is contemplative, its language is descriptive and precious, and it is not a book where every single word moves the plot forward. This is not a quick-paced page-turner. Readers who love books that move fast and are heavy on plot, rather than characters and atmosphere, might find it slow and decide nothing much happens in it. There is plenty that happens though, and I could not help but feel that the book also sounds a note of caution and warning, because it is impossible to read about some of the events, the politics, and the reactions of the populations and not make comparisons with current times. As I sometimes do, although I have shared some quotes from it already, I’d advise possible readers to check a sample of the book before making a decision about it. This is not a book for everybody. If you enjoy reading as a sensual experience, appreciate the texture and lyricism of words, and love books about art that manage to capture the feeling of it, I cannot recommend it enough. It is beautiful. This is the first book by this author I’ve read, and I’m sure it won’t be the last.

Log in with Facebook

Log in with Facebook