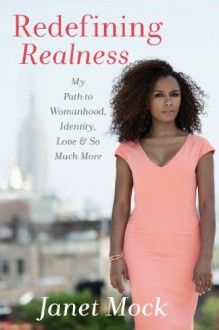

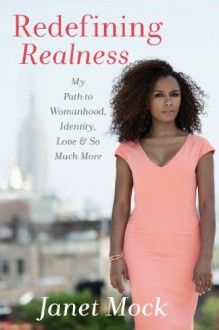

I’ve been interested in this book ever since hearing Janet Mock talk on The Colbert Report (segment here). I loved her willingness to laugh at herself, her attempts to focus the disconcerting Colbert, her willingness to articulate identity issues on a show that specializes in sarcasm. Only in her late twenties, she’s written the story of her process of gender identity to date in Redefining Realness, an autobiography that is occasionally as telling for what is included as minimized.

Redefining Realness starts with an Author’s Note, an Introduction, and an untitled preface of New York City, 2009, and her decision to share her past with a boyfriend who has become very close. As she takes a deep breath into disclosure, the narrative dives into her past, transitioning to Part One, Honolulu, first grade 1989. Having been born with male genitals, Janet was named ‘Charles’ after her father, but recalls feeling female gendered since her earliest years. She relates a story where a childhood friend, Marilyn, dared her to put on a dress hanging on the clothesline. It became a Big Deal, with Grandma catching her, her sister tattling and her mom having a Conversation. The anecdote becomes a point to begin educating the reader about the process of gender definition, the cultural norms that assign items as gendered (hair, clothes, walk, etc.) and how they are reinforced through our daily acts. The juxtaposition of the intellectual deconstruction with her life events foreshadows a pattern continued through her narrative.

Janet segues into her parents’ history, her witnessing of her dad’s ongoing affair, her mother’s discoveries leading to suicide attempts and dissolution of the marriage. The separation precipitated Janet’s dad moving to Oakland and, once her mom was pregnant with a new child and in a new relationship, Janet joining him. The rest of the narrative covers time in Oakland with her dad and his addiction issues, and the move to Texas and his family. Part Two begins with Janet’s return to Hawai’i in 1995. Throughout her moves, Janet relates moments where her gender identity was a struggle. Part Three begins with her claiming the name ‘Janet’ out loud to her high school as a sophomore, and the steps that followed as she became more out about claiming a female identity and seeking to make her identity a biological reality.

Two completely random observations: Interestingly, though Janet doesn’t overtly discuss it, many of those early gender moments are centered around hair, whether admiring the silky long hair of her mother, or her father punishing her by taking her to the barber for a short haircut. I found it particularly interesting as hair is a powerful touchstone in African-American culture, and Janet seemed to seize on it as part of establishing her femininity. Second, Hawaiian culture (and perhaps culture of the late 90s?) seems to be far more comfortable with gender ambiguity than most areas in America.

What can you say about someone’s heartfelt autobiography? I’m not qualified to judge anyone’s life; what I look for in autobiography are the moments of emotional honesty that cut to the heart of human experience, that acknowledge the complexity of what it means to be human with all of our good intentions and sad mistakes. Mock’s autobiography largely succeeds here, although with an emotional brevity that somewhat limits the feeling of engagement.

I appreciated Mock’s attempts to transcend the specifics of the individual experience, reflecting on the larger social issues that contextualize her experience. For instance, in the section where she discusses her childhood sexual abuse, she also relates some facts about sexual abuse offenders. In the section on sex work, she also integrates discussion of defined womanhood as well as the economics of survival sex work. At times, the deconstruction provides excellent insight into the situation from a cultural perspective; at other times, it makes for sweeping generalities that minimize the emotional complexities. Occasionally, the pieces also feel a little bit Gender Studies 101, although I acknowledge my intellectual exposure in the genre is greater than many readers’, it lacked some of the subtlety and finesse I expected from someone blurbed by bell hooks.

More disappointing are a couple sections that are minimized, particularly the less than one-page mention of losing her virginity at the age of sixteen. I don’t think it is voyeurism as much as wanting to know how she negotiated an emotionally loaded experience in any human’s life, beyond a passing note of, “weeks later, I lost my virginity…” But memory is tricky, and in my own case, what I think I remember about my own experience is no doubt different than my memories of it in my twenties, and then again in my thirties. Is it fair to ask that Mock share it? I don’t know, but for most of us, gender is tied up in sexuality, and in Mock’s own story, she makes it clear that while it is related, it is also complicated. I think I wished for more of those sorts of discussions than experiences of buying her first lip gloss or hanging at the MAC makeup counter.

By the end, I admired Mock’s willingness to share so much, to acknowledge the times she was perhaps (understandably) focused on her survival at the expense of others (the very definition of adolescence), and to recognize and celebrate her multiple identities. Very briefly, as part of her narrative of the sex trade, Mock acknowledges with amazing honesty “kindness and compassion are sisters but not twins… to have compassion for these men would mean that I’d have to know them and they would have to know me.” It proved a telling line, although likely not quite in the way she meant it. I found at times she was very self-critical, sounding unforgiving for perspectives I’d attribute to the arrogance of youth. I give her credit–I don’t know that I’d ever publish an entire book exposing my childhood as well as innumerable coming-of-age vulnerabilities. I hope she can find some compassion for herself.

Log in with Facebook

Log in with Facebook